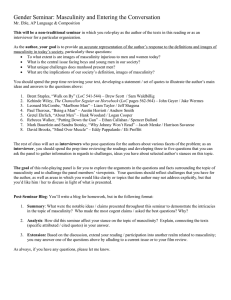

LOST IN MASULINITY LOST IN MASCULINITY: A CRITICAL RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF

advertisement