HOW WILL EAB CHANGE OUR FORESTS? A THESIS

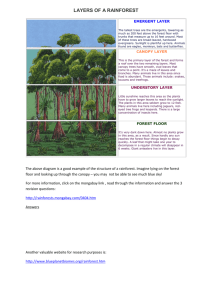

advertisement