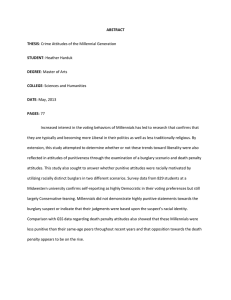

CRIME ATTITUDES OF THE MILLENNIAL GENERATION A THESIS

advertisement