HIST 498(Orientalism and Its Critics)

advertisement

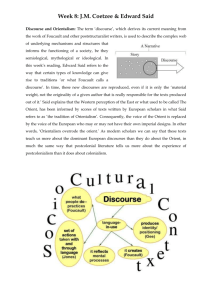

HIST 498(Orientalism and Its Critics) Spring 2015 219 Gregory Hall, 10:00-11:50 AM Prof. Behrooz Ghamari bghamari@illinois.edu 406 Gregory Hall Office Hours: T-TR 1:00-2:00 DESCRIPTION How do we study the history and culture of a people unknown to ourselves without projecting our own values and views upon them? The goal of this class is to problematize the possibility and the means through which westerners have depicted and imagined non-westerners, thus the term “orientalism.” Orientalism comprises a wide range of historical, social, literary, and popular writings as well as other forms of artistic production (painting, photography, films) that sought to uncover the essential features of non-Western civilizations, particularly in the Middle East and the continent of Asia. In its textual form, Orientalism was based on the study of original texts, which were assumed to be representative of the essence of these civilizations. Exoticizing the Orient through visual (pornographic) depiction was another aspect of Orientalism. Although we can trace the fascination with the Orient to ancient times, this class will focus primarily on the historical period of the expansion of modern Europe since the time of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century. Linking Orientalism to the project of the Enlightenment serves historical and epistemological purposes. The historical and epistemological significance of Orientalism lies on the one hand in its particular way of dealing with the alien and construction of "the other", and on the other hand, in its institutional relation with European colonialism and imperialism. The main objective of this class is to use primary documents available in the library in order to develop a map of Orientalist perceptions. There are a number of issues that we need to deal with in the class. First and foremost, what does count as primary document? For the purpose of this class, I have divided these documents into three different categories, textual documents, photographic images, and the arts. The main focus of our class will be on the textual documents. These include: travelogues, administrative reports from the colonies, missionary accounts, and other possible depictions and representations of people from the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia and possibly Africa. COURSE REQUIREMENTS AND EVALUATION Required Readings: Available for purchase at the university bookstore: Edward Said, Orientalism, Vintage, 1978. Alexander Lyon Macfie, Orientalism: A Reader, NYU Press, 2001. Zachary Lockman, Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism, Cambridge University Press, 2nd Edition 2010. Reina Lewis, Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel, Ottoman Harem, Rutgers University Press, 2004. For additional reading materials, check the class Compass page. Attendance & Participation in class discussion is required. More than FOUR unjustified absences from class will result in a failing grade. You will lose 1% of your final grade for each unjustified absence. This is a discussion class, so I will not be giving any lectures and you are responsible for reporting your research activities in class. We shall try to link the reading material to your research. We will divide the class into four teams of two or three. Each team will conduct its own research on 3 different genres of primary documents. For each topic, the group has to create a power point presentation in class. Each member of the group needs to write an individual two-page text that explains what their primary document is and how one can read it through a critique of Orientalism. (I will explain how to do this in class). I will upload the presentation onto the Compass page. At the end of the class, pending on technical logistics, we will create a web site on Orientalism. Midterm Take-Home Exam: March 17. The midterm is going to be an exam based on the literature we cover in class in short essay format. Final Paper: Due May 12. We’ll discuss the project later in class. Plagiarism: (Please Read Carefully) We have a zero tolerance of plagiarism. Not knowing what constitutes plagiarism cannot be used as an excuse for violating the trust between a professor and a student. We define plagiarism as representing the words or ideas of another as one’s own. Submitting papers not written by the student is only the most blatant form of plagiarism. Plagiarism also includes, but is not limited to: copying another student’s work in exams, 2 papers, or other exercises; inappropriate collaboration with another student; and verbatim copying, close paraphrasing, pasting in, or recombining published materials, including materials from the internet, without appropriate citation. For further consultation see: http://www.history.illinois.edu/courses/plagiarism/ Grading and Evaluation: Participation in class 3 research projects and presentation Take-home exam (March 10-17) Final Paper Total 50X3 Points 100 150 100 150 500 Percentage 20% 30% 20% 30% 100% CLASS SCHEDULE Week 1 (Jan 20) Welcoming chat and discussion about the goals and objectives of the class. This week, I would offer a lecture on general issues of Orientalism and the problems of Orientalist historiography. Watch in class The Sheik, silent movie based on a popular 1919 novel by Edith Hull. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MBj1lpAAclI Week 2 (Jan 27) In this week’s reading, we will explore some of the ways in which Christians living in the region that we think of today as Western Europe during the medieval period came to perceive Islam, the new faith that emerged in the Arabian Peninsula in the third decade of the seventh century. As we will see, even the initial Western Christian perceptions of Islam and of its adherents did not come out of nowhere or develop in a vacuum. Some of these concepts and categories, and the images they generated, would prove quite durable over much of the medieval period, though by the end of this period a handful of scholars had begun to lay the basis for a somewhat better understanding of Islam. In the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, the sense that Islam posed an imminent military and ideological thereat receded. The Latin Christians thought that the Mongols had been sent by God to destroy Islam once and for all. They made a number of attempts to form alliances with them, but failed. This week we shall read about the emergence of a more sustained boundary between Europe and the land of Islam, focusing particularly on how these boundaries were reflected in the way European Christians understood their Oriental neighbors. Reading: Zachary Lockman, Contending Visions of he Middle East, Chapters 1 and 2, pp. 8-65. 3 Week 3 (Feb 3) Great post-Enlightenment philosophers and historians often viewed the Orient as a place without history. This week we shall read short excerpts from J. S. Mill, Hegel, and Marx. Here we need to keep in mind, that despite their political differences, these philosophers shared similar views about oriental civilizations. We will also look at the rise of Orientalism as a scholarly discipline. Readings: (All in A. L. Macfie’s Orientalism Reader, NYU Press, 2000) James Mill: “The Indian for of Government,” pp. 11-12. G. W. F. Hegel: “Gorgeous Edifices,” pp. 13-15 Karl Marx: “The British Rule in India,” pp. 16-19 Pierre Martino: “Les Commencements de l’orientalisme,” 21-30 Raymond Schwab: “The Asiatic Society of Calcutta,” 31-35. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Europeans and Americans would increasingly come to see the Orient as divided into two distinct units: a “Near East” comprising southeastern Europe, the Levant (the land s along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean and their hinterland), and other parts of western Asia nearer to Europe, and a “far East” encompassing India, southeast Asia, China, and Japan. By the later part of the nineteenth century, in popular usage in the United States, the term “Oriental” had come to refer largely to people from East Asia. Nonetheless, the Orient remained a powerful category in nineteenth century European popular as well as scholarly culture. Readings: Zachary Lockman, “Orientalism and Empire,” chapter 3 in Contending Visions, pp. 66-98. From Orientalism Reader: Friedrich Nietzsche, “Appearance and the Thing-in-Itself,” pp. 37-39. Antonio Gramsci, “On Hegemony and Direct Rule,” pp. 39-41. Michel Foucault: “Truth and Power,” pp. 41-46. Week 4 (Feb 10) Arrange to meet the librarian In this week’s readings, we learn how Orientalist thought informed dominant political ideas in the West and conditioned the ideological frames of the twentieth century world order. We also read about how social and political changes around the world raised questions about Orientalist presuppositions. Readings: Zachary Lockman, Condenting Visions: “The American Century,” and “Turmoil in the Field,” pp. 100-182. Readings: From Macfie’s Orientalism Reader: Anouar Abdel-Malek, “Orientalism in Crisis,” pp. 47-56. L. Tibawi, “ English-Speaking Orientalists,” pp. 57-76. Bryan Turner, “Marx and the End of Orientalism,” pp. 117-119. 4 Week 5 (Feb. 17) This week will devote our attention to the writings of the most influential critic of Orientalism, Edward Said. Edward Said's book, Orientalism, is the first time that all three dimensions of Orientalism––a mode of thought, an academic discipline, and a corporate institution––come together as a multi-layered dominating discourse. Said separated himself from other critics by arguing that the goal of his analysis was not to define a real Orient against its ideological representation by Orientalist scholarship. Rather, he wanted to critique the very practice of representation and to construct Orientalism as an apparatus of power/knowledge. Said’s critique is not concerned with correspondence between Orientalism and the Orient, rather it is focused on the internal consistency of Orientalist ideas about the Orient. This internal consistency, Said contended, is marked by the belief in an epistemological and ontological distinction between the West and the Orient. Readings: From Edward Said’s Orientalism, Vintage Books, 1979. “Knowing the Oriental,” pp. 31-49. “Imaginative Geography and Its Representations: Orientalizing the Oriental,” pp. 49-73. “Projects,” pp. 73-92. “Crisis,” pp. 92-110. Week 6 (Feb 24) Edward Said’s Orientalism made a considerable impression on the academic world. In the period immediately following its publication, at least sixty reviews and review articles appeared in Britain and America. This week, we shall read a number of these reviews. Some critics expanded Said’s ideas, and some chastised the book for failing to see notable distinctions between Orientalist writings of different periods and different places. Readings: From Macfie’s Orientalism Reader: Stuart Schaar, “Orientalism at the Service of Imperialism,” pp. 181-193. David Kopf, “Hermeneutics versus History,” pp. 194-207. Michael Richardson, “Enough Said,” pp. 208-216. Sadik Jalal al-‘Azm: “Orientalism and Orientalism in Reverse,” pp. 217238. Ernest J. Wilson III, “Orientalism: A Black Perspective,” pp. 239-248. Bernard Lewis, “The Question of Orientalism,” pp. 249-270. Reading: from Zachary Lockman, Contending Visions: “Said’s Orientalism: A Book and Its Aftermath,” pp. 183-215. Week 7 & Week 8 (March 3 & March 10) (CLASS PRESENTATIONS) At this point you are ready to do some research based on primary documents in the library. We will devote these two weeks to your class presentations. 5 Weeks 9-10 (March 17-March 31) We should not imagine “Orientals” merely as objects to be represented by westerners. Not only was Orientalism criticized for it a-historical and essentialist depiction of non-western subjects, but also its representations were incessantly challenged from within the non-western world. As we have already learned, Orientalism is a deeply gendered view of the world, where nature/orient/ women are transformed into objects of exploitation and dominance by western/masculine/rational actors. For the next two weeks, we shall read three chapters from Reina Lewis’s book and see how she questions the prevailing stereotypes of the subjugated, silenced woman of the harem. Readings: From Reina Lewis, Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel, ad the Ottoman Harem, Rutgers University Press: 2004. Chapter 2, “Empire, Nation, and Culture,” pp. 53-95. Chapter 3, “Harem: The Limits of Emancipation,” pp. 96-141. Chapter 6, “Dress Acts: The Shifting Significance of Clothes,” pp. 206-250. Week 11 (April 7) (3rd CLASS PRESENTATION) Third presentation with a focus on gendered representations and counterrepresentations. Week 12 (April 14) We shall end our reading with a look at the political consequences of orientalist thinking in the contemporary world. We shall scrutinize how this academic discipline influences policy decisions at the highest echelons of the American government, particularly at a time when “Islam” and the “Middle East” have emerged as the main predicament of American foreign policy. Readings: Zachary Lockman, Contending Visions, chapter 7, “After Orientalim,” pp. 215-267. Week 13 (April 21) Watching the silent movie The Sheik once more to see how much our understanding of the narrative and representations have changed Week 14-15 (April 28-May 5) Presentations of the final project and concluding remarks. Final paper due May 12, before 5 PM 6