Corruption and Elections: An Empirical Study for a Cross-Section of Countries

advertisement

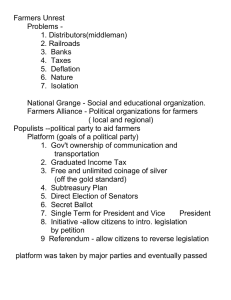

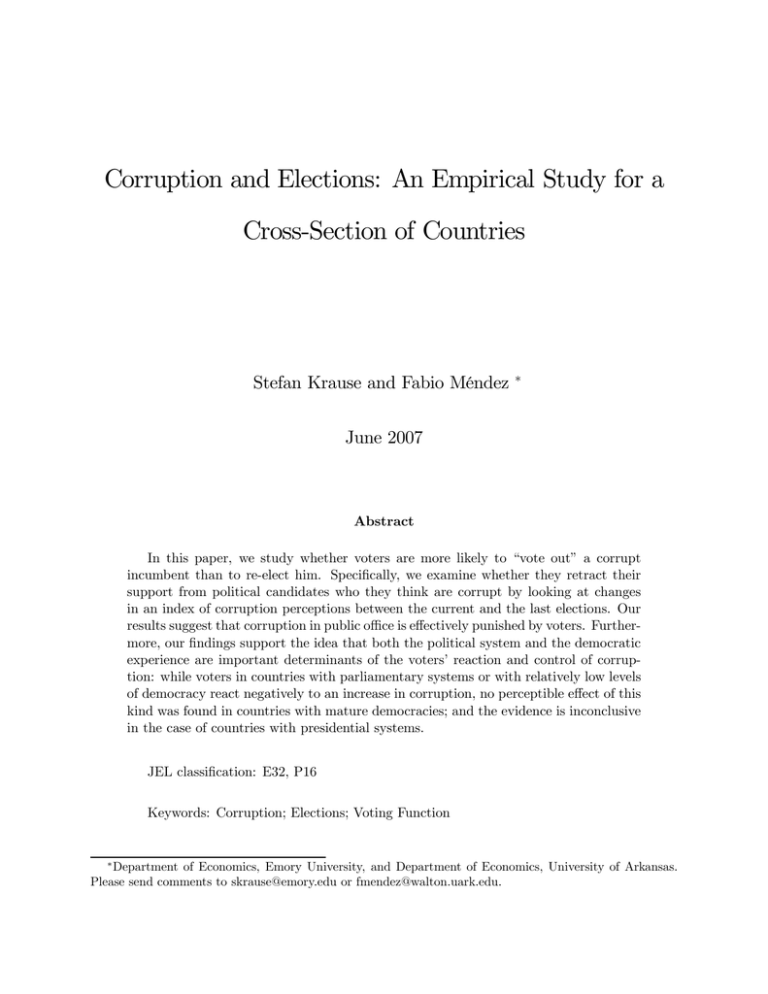

Corruption and Elections: An Empirical Study for a Cross-Section of Countries Stefan Krause and Fabio Méndez ∗ June 2007 Abstract In this paper, we study whether voters are more likely to “vote out” a corrupt incumbent than to re-elect him. Specifically, we examine whether they retract their support from political candidates who they think are corrupt by looking at changes in an index of corruption perceptions between the current and the last elections. Our results suggest that corruption in public office is effectively punished by voters. Furthermore, our findings support the idea that both the political system and the democratic experience are important determinants of the voters’ reaction and control of corruption: while voters in countries with parliamentary systems or with relatively low levels of democracy react negatively to an increase in corruption, no perceptible effect of this kind was found in countries with mature democracies; and the evidence is inconclusive in the case of countries with presidential systems. JEL classification: E32, P16 Keywords: Corruption; Elections; Voting Function ∗ Department of Economics, Emory University, and Department of Economics, University of Arkansas. Please send comments to skrause@emory.edu or fmendez@walton.uark.edu. 1 Introduction As established in both the economics and political science literatures, the question of whether politicians are held accountable for their policies plays a key role in controlling corruption and preventing bad governance (see, for example, Ferejohn (1986), Wittman (1989), Fackler and Lin (1995), Persson et al. (1997), and Lederman et al. (2005)). In general, greater political accountability is regarded as beneficial, for it helps to narrow the gap between the citizens’ objectives and the politicians’ choices. In modern democracies, citizens may punish corrupt politicians by voting them out of office, and they may reward honest behavior by re-electing an incumbent. Yet, as discussed by Rundquist, Strom and Peters (1977), and by Peters and Welch (1980), the reaction of voters to corruption in public office is complex and there are several reasons why voters could choose to re-elect a corrupt politician.1 - Voters may not be well informed about the incumbent’s behavior and may not hold her responsible. - Voters may be willing to endure a corrupt public official in exchange for periods of prosperity and general economic wellbeing. - Voters may see corruption as a personal flaw and while they would not support a corrupt candidate, they would still be willing to vote for that candidate’s party. - When corruption is used to benefit certain ethnic or social groups, voters from these groups might reward corrupt politicians and help her avoid a general loss of votes. In this paper, we study whether voters are more likely to “vote out” a corrupt politician than to re-elect him. More specifically, we examine whether voters retract their support from political incumbents who they think are corrupt. We do so by studying the empirical relationship between changes in the electoral votes received by incumbents and changes in the perceived levels of corruption in a sample of 28 countries during the period of 1995-2006. 1 A useful link to public information and press releases regarding corruption in electoral process is the website for Transparency International (http://www.transparency.org/), which contains a substantial number of articles and news stories about corrupt politicians seeking and obtaining re-election. 1 Similar studies analyze the effects of corruption charges on electoral results using data for a single country only. Peters and Welch (1980), for example, study the electoral impact of corruption charges on candidates in contest for the U.S. House of representatives. They estimate that candidates accused of corruption suffer a loss of 6-11% of the expected vote. Similarly, Chang and Golden (2004) find that charges of corruption significantly decrease the re-election probability for Italian congressmen. In turn, Fackler and Lin (1995) collect news stories and report a negative correlation between the amount of information about corruption and the electoral support for the party in control of the presidency in the USA. Ferraz and Finan (2005) report similar results for the case of Brazil. In contrast with all these other papers, we use a cross-sectional sample of European, North and South American countries, plus Japan. One noticeable advantage of using a cross section of countries is that we are able to split our sample according to the system of representation chosen by each country (presidential or parliamentary), and by their democratic experiences in the post-war years. Splitting the sample in such ways allows us to explore the arguments of Ferejohn (1986), Treisman (2000), and Lederman et al. (2005); who have suggested that both, the type of political system and the exposure to democratic institutions, play a determinant role in the electorate’s control of corruption. Lederman et al. (2005) report that corruption is lower in countries with parliamentary systems and where democracy has gone uninterrupted for a number of years. Treisman (2000) also reports a negative correlation between long exposure to democracy and corruption. Both of these studies interpret their results as evidence that the political structure and the electoral system help determine the incentives for those in office (to be honest), and for the citizens in general (to police and punish corrupt behavior). Noticeably, however, they do not investigate whether their interpretation is consistent with the evidence from electoral results.2 Throughout the paper we use aggregate indices of corruption perceptions instead of accounts of corruption charges. Thus, our measure of corruption does not reflect the actual 2 Also, see Ferejohn (1986) for a theoretical model where the voters’ control on office holders depends on the political regime assumed. 2 behavior of the incumbent, but the voters’ perception of his behavior. The particular index of corruption perceptions used in this study is the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) from Transparency International, which we shall describe in more detail on Section 2. The results of the paper regarding the effects other economic variables on the votes received by the incumbent are consistent with those of previous studies in the literature: higher output growth and lower inflation increase the incumbent’s support.3 In turn, with regards to the effects of changes in the level of perceived corruption on the electoral support for the incumbent, we find that an increase in corruption is positively associated with a loss of votes in the general sample. Hence, our results suggest that corruption in public office (or the perception thereof) is effectively punished by voters at the same time that good economic conditions are rewarded. Furthermore, our results support the idea that both the political system and the democratic experience are important determinants of the voters’ reaction and control of corruption. While our findings suggest that voters react negatively to higher levels of corruption in countries with parliamentary political systems, in countries with presidential systems the evidence is less conclusive. As for the democratic experience, we find that increased corruption is punished only in countries with relatively short exposure to democracy, with no perceptible effect in mature democracies. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed description of the data set used for this study. Section 3 presents the main econometric specifications, while Section 4 shows the estimation results. Finally, Section 5 concludes. 3 See Persson and Tabellini (1999), and Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (2000) for a discussion of these issues. 3 2 Data description The data used in the empirical analyses includes 28 countries and covers years between 1995 and 2007. For each electoral round, we collected data for the polling results, and the political and economic conditions that characterized it. The set of countries in our sample are mainly European and North and South American countries. Out of the total sample, 17 countries have a parliamentary system and 11 have a presidential system. An effort was made to obtain data from as many countries and electoral periods as possible; however, the sample size was limited by the availability of data, as is the case for other empirical studies. Paldam (1991), for example, uses data from 17 high-income democracies over the period 1948-1985. Similarly, Lewis-Beck and Mitchell (1990) use a data set limited to 5 nations and 27 elections. Powell and Whitten (1993) use a cross section of 19 industrialized nations for the period 1969-1988. In our particular case, the sample is restricted by the availability of corruption perception measures (the CPI index, for example, was first reported in 1995), and the data on political parties and electoral results (since we require data for at least two complete electoral periods). When matching the CPI data with information on political systems we are able to construct a data set that includes 28 countries and a total of 93 elections. All sources and variable definitions are summarized in a data appendix.4 Data on political parties and electoral results was obtained from three main sources: The Dataset of Political Institutions (DPI) introduced by Beck et al. (2001) was the main source. Two other complementary sources were used: the Political Dataset of the Americas (managed by the Center for Latin American Studies at Georgetown University in collaboration with the Organization of American States), and the database for European political parties and elections.5 4 The complete data set can be downloaded at http://comp.uark.edu/~fmendez/data. "Parties and Elections in Europe" includes a database about parliamentary elections in the European countries since 1945 and additional information about the political parties and the acting political leaders. The private website (http://www.parties-and-elections.de) was established by Wolfram Nordsieck in 1997. 5 4 Electoral systems were broadly classified as Presidential or Parliamentary following the DPI’s classification. For presidential systems, the incumbent’s votes correspond to the votes obtained by the party with which the incumbent president is associated. For parliamentary systems, the incumbent’s votes correspond to the votes obtained by the party with the largest presence within the government. Notice that according to this definition, the incumbent party in a parliamentary system may well not constitute the party with greatest amount of seats. In parliamentary systems, whenever a number of small parties collude to form a coalition government, the party that obtains more seats is not necessarily the one who is in charge of making policy (and is therefore blamed for good or bad performance). Thus, defining the incumbent in this way has the advantage of assigning responsibility to the actual policy maker. For both systems we recorded the percentage of the votes obtained by the incumbent as well as the percentage of votes obtained by that same party in the previous elections (when it came to power). We also collected information on the percentage of parliamentary seats the incumbent’s party controlled at the time of the elections, and information on ideological identification to create a dummy variable taking the value of 0 for left oriented parties and 1 for right or center oriented parties. In addition, we use a measure of the length of the electoral cycle (in number of months between elections) and the degree of fractionalization of the ruling government, as defined by the probability that two random draws from parliament would produce legislators from different parties (Beck et al. (2001)). To capture the exposure to democratic institutions, we classify countries as “mature” or “new” democracies. In order to do so, we employ annual measures for institutionalized democracy (DEMOC), available form the Polity IV dataset and developed by Marshall and Jaggers (2002). The DEMOC indicator is based on an additive eleven-point scale (0-10). We average these scores over the period 1949-2003 for each of the 28 countries in our sample and identify “mature” democracies with countries for which the average value for DEMOC is equal to 10, and include Japan, for which the value equals 9.45. Similarly, we identify 5 “new” democracies with countries for which the average value of DEMOC ranges between 3.11 (El Salvador) to 7.16 (Greece). There are 14 countries classified as “mature” and 14 countries classified as “new”. In turn, for measuring changes in corruption perceptions we use the corruption perceptions index (CPI) from Transparency International. The CPI is “an index that draws on multiple expert opinion surveys that poll perceptions on public sector corruption” and the corruption of politicians (Transparency International, press release 2006). As of 2006, the CPI has the greatest scope of countries of any perception index available (163 countries), and has been used in multiple empirical studies (see, for example, Herzfeld and Weiss (2003), and Persson et al. (2003)). The CPI is a composite index that draws on 12 different polls from 9 independent institutions and scores countries on a scale from zero to ten; with zero indicating high levels of perceived corruption and ten indicating low levels of perceived corruption. For our purposes in this paper, we are interested in measuring whether perceived corruption has increased during the incumbent’s tenure or not. Thus, we use yearly CPI values to calculate the change in CPI between the time the incumbent took office and the time the elections take place. That is, we create the variable PCI (i.e., perceived corruption increase) which is defined as P CI = −(CP It+e − CP It ), where t represents time (in years), and subscript e represents the number of years between elections. A positive value for PCI corresponds to a perceived increase in corruption, while a negative value corresponds to a perceived decrease in corruption. Finally, data for all the economic variables, namely GDP growth, inflation and unemployment, was obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators Database (2006). In the empirical section, we use the annual indices of each economic indicator averaged over the duration of the electoral cycle in question. 6 3 Model Specification For the econometric specification, we adopt a general voting function in which political and economic variables enter simultaneously as determinants of voting behavior. As in most of the economic voting literature (see Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2000; Paldam, 1991; and Powell and Whitten, 1993), the dependent variable is the gain (or loss) in the share of votes received by the incumbent party with respect to the previous election. This change is explained by a series of economic and political variables included in a set of explanatory variables. With regards to the economic indicators used as explanatory variables, we include a measure of GDP growth and consumer price inflation. In some specifications we also control for the behavior of unemployment. As explained before, all of these measures correspond to the annual indices of each economic indicator, averaged over the duration of the electoral cycle in question. Previous studies have reported a connection between all of these economic variables and both the popularity of the government and the votes obtained by the incumbent (see, for example, Paldam (1991) or Powell and Whitten (1993)). In these studies, after controlling for political variables that influence electoral results, an increase in the number of votes received by the incumbent is associated with pre-electoral periods of elevated growth and moderate inflation.6 In turn, the political variables used as independent variables include a measure of absolute government support, a measure of the length of the incumbent’s tenure (in years), the ideological classification of the incumbent, the number of parliamentary seats controlled by the incumbent, and the degree of fractionalization in the government. Below, we provide some intuition for why these controls are important. As we discuss in Section 4, our main 6 See Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (2000) for additional evidence in the case of US elections; Nordhaus, Alesina and Schultze (1989) for evidence on inflation and unemployment performance; and Abrams and Butkiewicz (1995) for an analysis of how state-level economic conditions have incidence on presidential elections. 7 results are robust to the inclusion of these control variables. As noticed by Powell and Whitten (1993), since different parties have different electoral bases that remain stable over time, using the results of previous elections to control for absolute government support is essential to the specification: “A loss of two percentage points may mean something different for a government that won 40% last time as compared with a government that won 60% last time.” We agree with this appreciation and include this control in some of our specifications. Also as in Powell and Whitten (1993), we expect its coefficient to be negative as it is easier to lose an absolute percentage of the votes from a larger base. We include a measure of the length of the incumbent’s tenure (in years) to capture the depletion in government support that appears as the government ages and the initial popularity of the government vanishes. Such loss of popularity has been previously documented by authors like Goodhart and Bhansali (1970) and Paldam (1986). Since corruption may change as the end of the political tenure approaches, including the effects of the length in tenure may be relevant for our estimation. We also include a political ideology dummy and two variables that capture the cohesion of the government. The dummy variable takes a value of 1 for right or center oriented parties and a value of 0 for left oriented parties. Left and right leaning parties tend to have different preferences and approaches to economic policy and voters might take these historical trends into account when evaluating government performance. We also control for government cohesion, which is measured by government fractionalization and the number of congressional seats controlled by the incumbent at the time of the election. As explained by Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (2000), the greater the perceived cohesion of the incumbent’s government, the more likely voters are to charge the incumbent with the responsibility of recent policies and, thus, of any perceived corruption. Once our measure of the changes in corruption perceptions is included, the econometric specification can then be summarized by the following equation: 8 → − → − V otesch = α + βP CI + δ E + γ P , (1) where V otesch is the absolute change in the percentage of the popular vote captured by the → − incumbent in any election with respect to the previous election; E is a vector of economic → − variables (growth and inflation); P is a vector of political variables (used as controls); and PCI, as before, represents the increase in perceived corruption. 4 Empirical analysis and results Table 1 shows a descriptive summary of all variables of interest for each country, averaged over each government period. Noticeably, the 28 countries in our sample exhibit sharp differences in average perceived corruption (ranging between 3.65 for Turkey and a 8.86 for the Netherlands), GDP growth (from 0.44% for El Salvador and 4.03% for Hungary) and Consumer Price Inflation (-0.04% in the case of Japan and 69.18% for Turkey). Before examining the evidence of whether voters tend to punish a perceived increase in corruption on behalf of the incumbent and whether differences in the political system and the democracy levels translate into differences in the degree of reduction in support, it is useful to verify if the countries in our sample comply with the empirical observations made by Lederman et al. (2005) and Treisman (2000). These authors report that countries with presidential systems and shorter exposure to democracy tend to exhibit a higher degree of corruption. Looking at Table 2, we can observe how the 17 countries with parliamentary systems have an average corruption perceptions index of 6.87, nearly one point higher than for the 11 countries with presidential systems (5.88). Comparing mature democracies with new democracies yields an even larger difference: an average score of 7.19 for the former versus 5.78 for the latter. In both cases, a simple test of differences in means suggests that the respective averages from both sample splits are significantly different (to the 1% level in both 9 cases); consistent with the findings of those previous authors. We now turn our attention to the main question in this analysis; namely, whether voters tend to reduce their support for an incumbent when a perceived increase in corruption takes place. In this regard, the results from estimating equation (1) using least squares estimation for the entire sample are displayed in the first column of Table 3. For the total sample, the results of this estimation reveal that an increase in perceived corruption is significantly associated with a loss in voters’ support for the incumbent; and the coefficient is significant at the 1% level. As for the role of economic performance, consistent with previous findings, we also observe that a higher GDP growth rate is associated with an increase in voters’ support towards the incumbent, while higher inflation is correlated with a punishment by voters in terms of diminished support. Both coefficients are significant at the 1% level. Finally, the unemployment rate does not enter the regression with a significant coefficient. Focusing our attention on the political conditions, we do not find significant evidence suggesting they affect voters’ behavior, once we control for changes in perceived corruption and our economic performance. In particular, we do not observe a reduction in the incumbent party’s support base, as discussed by Powell and Whitten (1993); or a wear down effect, as identified by Paldam (1991). Neither the votes obtained in the previous elections by the incumbent, nor the length of their tenure, seem to have a significant outcome on the change in voters’ support, albeit they do enter the regression with the expected negative coefficients. A potential explanation for this discrepancy with the findings by Paldam (1991), and Powell and Whitten (1993) is that, while their studies covers elections in industrialized countries, our sample also takes into account elections in emerging markets and transition economies (including 10 Latin American countries). Our main results are robust to alternative specifications. In the second column of Table 3 we include only the political variables as controls; and, while we still fail to identify evidence suggesting that other political conditions affect voters’ behavior, an increase in 10 perceived corruption remains negatively and significantly correlated with a change in the votes received by the incumbent. This key finding is also robust when controlling only for economic performance in the third column: the coefficients on perceived corruption increase, GDP growth, and inflation remain virtually unchanged, and are still significant at the 1% level; meanwhile, unemployment remains insignificant. Since this latter observation may be the result of voters being more concerned with aggregate activity than employment, we focus only on GDP growth and inflation as the economic control variables in the last column of Table 3. Overall, we find that across all different specifications, the evidence robustly points to an increase in perceived corruption resulting in a loss of votes by the incumbent. In Table 4 we examine whether differences in the political system also amount to differences in the degree of voters’ punishment to increased corruption. Two specifications are considered: the first includes only considers the principal economic variables (GDP growth and inflation) as explanatory variables, while the second incorporates political variables as controls. For countries with parliamentary systems, the results mirror the ones we obtained when considering the entire sample: a perceived corruption increase, lower GDP growth, and higher inflation are all significantly correlated with a loss of votes by the incumbent. These results are robust to controlling for political variables, and for country-specific effects (results displayed in column (1) of Table 6). As in the case of the entire sample, the political control variables do not appear with significant coefficients; the only exception is the percentage of votes the incumbent received in the previous election, which enters the regression with a negative sign. Therefore, for parliamentary systems we do observe a reduction in support due to a larger base, consistent with the findings of Powell and Whitten (1993). For presidential systems, the evidence from the last column suggests that only an increase in perceived corruption is significantly associated with a loss of voters’ support for the incumbent, and only at the 10% level. None of the economic variables enter the estimation with significant coefficients. However, we can infer from the overall goodness-of-fit statistics that there is quite substantial amount of variability of voting behavior in coun- 11 tries with presidential systems that is not explained by our right-hand side variables. To address this issue, we also include the political variables as controls, which did not generate any significant change either in the coefficients of interest, or in the overall goodness-of-fit. While none of the political controls enters the regression with a significant coefficient, their inclusion does result in the coefficient on perceived corruption increase becoming no longer significant. We also explored the possibility that extreme values for inflation in some countries with presidential systems may be responsible for the lack of precision in the estimates, so we employed a transformed rate of inflation, given by T RI = π/(π + 1), again without any noticeable change in the main results.7 Allowing once more for the possibility that country-specific effects may be warranted, we performed a random-effects estimation, whose results are reported in the second column of Table 6, only to find that the coefficient on the increase in perceived corruption becomes even less significant. This leads us to note that the evidence of a punishment by voters in presidential systems as a result of a higher degree of corruption is inconclusive, and not robust to alternative specifications. Finally, we perform our second sample split based on exposure to democratic institutions, and report the results in Table 5. Interestingly enough, voters in countries that have had stable democracies since the post-war do not seem to punish the incumbent party when they perceive an increase in corruption, whereas voters in relatively “new” democracies do significantly punish the governing party when they perceive an increase in corruption. These results are robust to controlling for the inclusion of political variables, as shown on columns (2) and (4) of Table 5; and to country-specific random effects, as shown in the last two columns of Table 6. As for the economic variables, GDP growth enters the regression with an expected positive and significant coefficient only for the sub-sample of “new democracies”, while inflation enters the regression with the expected negative and statistically significant sign for mature democracies (for “new” democracies the coefficient is substantially smaller in absolute value 7 These results are available upon request from the authors. 12 and becomes non-significant once we control for country specific effects). In short, our results suggest that while the empirical observation that corruption is lower in countries with parliamentary systems can be explained by the greater control that voters exert in those countries (and their dislike of corruption); the empirical observation that corruption is lower in countries with older democratic traditions cannot be explained by the voter’s control and punishment of corruption. Thus, the question of how does the length and stability of a democratic system affects its level of corruption remains unanswered. 5 Conclusions and Implications We evaluate the question of whether voters reduce their support for an incumbent, whenever they perceive an increase an increase in corruption, by looking at a sample of 28 countries and 93 election periods. Our results suggest that a perceived rise in corruption in public office is effectively punished by voters in the general election. For the entire sample, this result is significant and robust to alternative specifications of the voting functions. More specifically, our findings provide strong evidence that voters react negatively to an increase in corruption in countries with parliamentary systems, compared to presidential systems of government. A potential explanation for this result was discussed at the beginning of this paper: in presidential systems, voters may perceive corruption as a personal flaw associated with the current president and not necessarily with his or her party; while in parliamentary systems, voters associate corruption with the entire party. An alternative explanation could be that most of the countries in our sample with presidential system are Latin American. Finally, an increase in perceived corruption is punished more severely in countries with relatively short exposure to democracy, and not significantly so in mature democracies. This may be due to the fact that in relatively “newer” democracies, where voter turn-out during elections is, on average, higher than in established democracies, the electorate becomes more 13 vigilant of the incumbent’s actions, creating a larger margin for punishment or reward at the time of the elections. 6 Data Sources and Description 6.1 Appendix 1: The Electoral Results for Incumbents (ERI) Data Base The countries with presidential system included in the sample are: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Uruguay, and USA. The countries with parliamentary system included in the sample are: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Data is available for download at: http://comp.uark.edu/~fmendez/data. Sources of information 1. The World Bank’s Data Set for Political Institutions (DPI); Dataset of Political Institutions (DPI) introduced by Beck et al. (2001) 2. Political Dataset of the Americas (managed by the Center for Latin American Studies at Georgetown University in collaboration with the Organization of American States) 3. The database for European political parties and elections. “Parties and Elections in Europe" includes a database about parliamentary elections in the European countries since 1945 and additional information about the political parties and the acting political leaders. The private website (http://www.parties-and-elections.de) was established by Wolfram Nordsieck in 1997. 4. The World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). 14 Data on electoral dates (used to compute the length of the incumbent’s tenure), party ideology, votes received by incumbent, incumbent’s seats in congress, fractionalization of the governing coalition, were obtained mainly from the Database on Political Institutions in Beck et al (2001), the Political Dataset of the Americas (managed by the Center for Latin American Studies at Georgetown University in collaboration with the Organization of American States), and the database for European political parties and elections, and also partly completed through direct inquiries to individual government sources. Data on GDP growth, inflation and unemployment was obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (2004). 6.2 Appendix 2: Variable definition and methodology Note: Each data point corresponds to a democratically held election. cname: Country name. id: Country identification number. Syst: Dummy variable. Syst =0 for countries with presidential systems. Syst=2 for countries with parliamentary systems. Syst=1 for countries with mixed presidential system. This classification matches the one provided in the DPI. eyear: Year when general elections took place. For countries with presidential systems, eyear contains those years when executive elections were held (starting from 1984). For countries with parliamentary systems, eyear contains those years when legislative elections were held (starting from 1984). These information was obtained from either the DPI, the EDSA, the EPD, or a combination of them. The three sources of data usually agree on the dates, but small corrections sometimes are required. emonth: Month of the year when elections took place. 15 peyr: Year when the previous general elections took place. pemonth: Month of the year when previous elections took place. cycle: Number of months spanning between elections. This number is presented in years, so that a 4.25, for example, represents for years and 3 months. growth: Average annual growth rate of GDP per-capita between the year in which the incumbent took office and the year of the elections. This variable is constructed by using the “GDP per capita growth (annual %)”, from the WDI. infl: Average annual change in consumer prices between the year in which the incumbent took office and the year of the elections. This variable is constructed by using the “Inflation, consumer prices (annual %)”, from the WDI. unempl: Average annual rate of unemployment between the year in which the incumbent took office and the year of the elections. This variable is constructed by using the “Unemployment, total (% of total labor force)”, from the WDI. vinc: Percentage of valid votes received by the incumbent party. For countries with syst=0, this number corresponds to the votes received by the party that holds the executive office. For countries with syst=2, this number corresponds to the votes received by the largest party in government. vincp: Percentage of valid votes received by the incumbent party in the previous election (that resulted in this party gaining control of the executive or, in the case of syst=2, that resulted in this party becoming the largest party in government). vchg: Decrease in voters support. vchg = vincp-vinc. yp: Number of years that the incumbent party has been in power. For countries with syst=0, this number corresponds to the number of years for which the incumbent 16 party has held the executive office. For countries with syst=2, this number corresponds to number of years for which the incumbent party has been the largest party in government. ideoinc: Dummy variable representing the political ideology of the incumbent party. For left-wing parties we assign a value of 0, while for right-wing parties we assign a value of 1. seats: Number of government seats in parliament (at the time of the elections) divided by total seats. This corresponds to the variable “majority” in the DPI data set for both parliamentary and presidential systems. govfrac: This variable corresponds to the government fractionalization measure of the DPI dataset. By definition, this variable has a value of zero for governments in presidential systems. cpi: This is the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) corresponding to the electoral year; or say, at the time the incumbent competes for office. The CPI was obtained directly from Transparency International (2006). pci: Increase in corruption perceptions measured by the change in the cpi index: PCI = -(CPIt+e — CPIt). 17 References [1] Abrams, B. A., and J. B. Butkiewicz (1995). “The Influence of State-Level Economic Conditions on the 1992 Presidential Election”, Public Choice, 85, pp. 1-10. [2] Beck, T., G. Clarke, A. Groff, P. Keefer, and P. Walsh (2001). “New Tools and New Tests in Comparative Political Economy: The Database of Political Institutions”, World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), pp. 165-76. [3] Chang, E., and M. A. Golden (2004). “Does Corruption Pay? The Survival of Politicians Charged with Malfeasance in the Postwar Italian Chamber”. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Hilton Chicago and the Palmer House Hilton, Chicago, IL [4] Fackler, T., and T.-M. Lin (1995). “Political Corruption and Presidential Elections, 1929-1992”, The Journal of Politics, 57(4), pp. 971-993. [5] Ferejohn, J. (1986). “Incumbent Performance and Electoral Control”, Public Choice, 50(1-3), pp. 5-25. [6] Ferraz, C., and F. Finan (2005). “Exposing Corrupt Politicians: The Effect of Brazil’s Publicly Released Audits on Electoral Outcomes”, mimeo. [7] Goodhart, C. A. E., and R. J. Bhansali (1970). “Political Economy”, Political Studies, 18, pp. 43-106. [8] Herzfeld, T., and C. Weiss (2003). “Corruption and Legal (In) effectiveness: An Empirical Investigation”, European Journal of Political Economy, 19, 621-632. [9] Lederman, D., N. Loayza, and R. R. Soares (2005). “Accountability and Corruption: Political Institutions Matter”, Economics & Politics, 17(1), pp. 1-35. 18 [10] Lewis-Beck, M. S., and G. Mitchell (1990). “Transnational Models of Economic Voting: Tests from a Western European Pool”. Revista del Instituto de Estudios Economicos, 4, pp. 65-81. [11] Lewis-Beck, M. S., and M. Stegmaier (2000). “Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes”, Annual Review of Political Science, 3, pp. 183-219. [12] Marshall , M. G., and K. Jaggers. (2002). Polity IV Dataset. [Computer file; version p4v2002] College Park, MD: Center for International Development and Conflict Management, University of Maryland. [13] Nordhaus, W. D., A. Alesina, and C. L. Schultze (1989). “Alternative Approaches to the Political Business Cycle”, Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 1989 (2), pp. 1-68. [14] Paldam, M. (1986). “The Distribution of Electoral Results and the Two Explanations of the Cost of Ruling”, European Journal of Political Economy, 2, pp. 5-24. [15] Paldam, M. (1991). “How Robust Is the Vote Function? A Study of Seventeen Nations over Four Decades”, Economics and Politics. The Calculus of Support. Edited by H. Norpoth, M. S. Lewis-Beck, and J. D. Lafay. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. [16] Persson, T., and G. Tabellini (1999). “Political Economics and Macroeconomic Policy”, Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 1C, edited by J. B. Taylor and M. Woodford, 1999, pp. 1397-1482. [17] Persson, T., G. Tabellini, and F. Trebbi (2003). “Electoral Rules and Corruption”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(4), pp. 958-989. [18] Persson, T., G. Roland, and G. Tabellini (1997). “Separation of Powers and Political Accountability”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, pp. 1163-1202. 19 [19] Peters, J. G., and S. Welch (1980). “The Effects of Charges of Corruption on Voting Behavior in Congressional Elections”, The American Political Science Review, 74(3), pp. 697-708. [20] Powell Jr., G, B., and G. D. Whitten (1993). “A Cross-National Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking Account of the Political Context”, American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), pp. 391-414. [21] Rundquist, B. S., G. S. Strom, and J. G. Peters (1977). “Corrupt Politicians and their Electoral Support: Some Experimental Observations”, The American Political Science Review, 71(3), pp. 954-963. [22] Treisman, D. (2000). “The Causes of Corruption: A Cross-National Study”, Journal of Public Economics, 76, pp. 399-457. [23] Wittman, D. (1989). “Why Democracies Produce Efficient Results”, Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), pp. 1395-424. 20 Table 1: Summary Statistics (Averages per government period for each country) Argentina President 3.69 Votes for Incumbent (%) 44.00 Austria Parliament 10.00 32.23 7.72 1.80 Belgium Parliament 10.00 15.25 6.64 2.04 1.70 10.50 1.00 58.66 78.26 Brazil President* 4.67 46.43 5.82 0.95 13.06 5.33 0.25 60.51 0.00 4 Canada Parliament 10.00 38.35 8.42 2.61 1.83 7.67 0.25 56.38 0.00 4 Country System Dem. Index Corruption Perception Index 5.07 GDP Growth (%) 1.04 Consumer Inflation (%) 0.76 10.00 1.00 62.12 0.00 2 1.85 14.00 0.40 60.38 45.04 5 3 Years in power Party Ideology Incumbent Seats (%) Fractionalization (%) # of Elections Chile President 4.42 49.97 8.21 3.54 4.87 13.00 1.00 55.00 0.00 3 Colombia President 6.58 57.63 6.90 2.31 6.11 4.00 0.50 10.00 0.00 2 Costa Rica President 10.00 31.90 6.64 2.45 11.08 6.00 0.67 40.35 0.00 3 Denmark Parliament 10.00 32.67 8.13 1.70 2.14 4.67 0.50 44.57 36.84 4 El Salvador President 3.11 54.84 4.35 0.44 2.10 15.00 1.00 57.14 0.00 2 4 Finland Parliament 10.00 24.40 7.80 3.15 1.28 5.33 0.50 66.88 67.25 Germany Parliament 10.00 38.12 6.20 1.28 1.47 9.00 0.50 51.01 32.69 4 Greece Parliament 7.16 42.43 6.72 3.43 3.87 9.00 0.00 53.15 0.00 3 Guatemala President 2.87 33.51 5.65 0.17 6.78 4.00 0.50 55.75 0.00 2 Honduras President 2.98 48.81 5.73 0.64 9.80 6.00 1.00 50.00 0.00 3 4 Hungary Parliament 2.58 36.93 6.15 4.03 12.71 4.00 0.00 59.58 34.25 Japan Parliament 9.45 34.01 6.32 1.12 -0.04 6.67 0.75 54.12 16.25 4 Mexico President 1.55 41.03 6.22 1.39 13.46 15.50 0.33 42.18 0.00 3 Netherlands Parliament 10.00 25.37 8.86 1.81 2.26 5.33 0.50 59.33 61.16 4 Norway Parliament 10.00 22.23 6.96 2.50 2.01 5.33 0.50 34.54 35.86 4 Portugal Parliament 4.98 39.78 7.20 1.65 3.09 5.33 0.50 50.07 6.98 4 3 Spain Parliament 4.65 41.38 5.44 2.69 2.85 6.00 0.67 52.00 12.47 Sweden Parliament 10.00 38.90 7.52 2.54 1.08 8.00 0.25 51.81 29.17 4 Switzerland Parliament 10.00 22.53 6.95 0.87 0.75 6.00 0.33 82.36 74.17 3 3 Turkey Parliament 7.13 14.08 3.65 1.55 69.18 3.50 0.33 50.81 56.13 United Kingdom Parliament 10.00 39.95 6.10 2.42 2.54 6.00 0.33 63.19 0.00 3 United States President 10.00 49.06 6.39 2.25 2.35 6.00 0.33 50.52 0.00 3 Uruguay President 6.31 26.57 3.75 0.20 15.85 7.50 0.67 91.12 0.00 3 Grand Average/Total - 35.33 6.70 1.97 6.50 7.37 0.49 54.81 24.36 93 * Mixed system with presidential elections. 21 Table 2: Average Corruption Perception Index across Elections Average Corruption Perceptions Index No. of countries Parliamentary System Presidential System Mature Democracies New Democracies 6.87 5.88 7.19 5.78 17 11 14 14 22 Table 3: Dependent variable: Change in votes of incumbent (Entire Sample) Economic and Political Political variables only Variables Economic variables only GDP growth and inflation only -3.306 (0.00) -3.318 (0.00) Perceived Corruption Increase -2.899 (0.00) GDP growth 2.252 (0.00) 2.497 (0.00) 2.501 (0.00) Inflation -0.154 (0.00) -0.142 (0.00) -0.142 (0.00) Unemployment 0.132 (0.65) 0.013 (0.96) Votes incumbent (previous election) -0.006 (0.98) 0.017 (0.94) Years in power -0.060 (0.74) -0.005 (-0.98) Party Ideology -0.580 (0.77) -2.893 (0.16) Incumbent seats -0.067 (0.50) -0.116 (0.27) Fractionalization 0.058 (0.44) 0.064 (0.41) R-squared 0.294 0.142 0.258 0.258 F-statistic 4.00 (0.00) 2.51 (0.03) 8.90 (0.00) 12.07 (0.00) -3.105 (0.01) Sample size for all specifications is 93 elections and 28 countries. p-values computed using robust standard errors are in parentheses. 23 Table 4: Dependent variable: Change in votes of incumbent (Pooled regression: Parliamentary vs. Presidential Systems) Parliamentary System Presidential System All variables Econ. Var. All variables Econ. Var. Perceived Corruption Increase -2.909 (0.01) -2.712 (0.00) -5.080 (0.17) -5.080 (0.09) GDP growth 2.151 (0.00) 2.102 (0.00) 2.658 (0.35) 3.051 (0.18) Inflation -0.144 (0.00) -0.115 (0.00) -0.256 (0.56) -0.413 (0.28) Votes incumbent (previous election) -0.290 (0.08) 0.388 (0.61) Years in power 0.100 (0.58) -0.235 (0.62) Party Ideology -0.502 (0.78) 2.105 (0.82) Incumbent seats 0.015 (0.19) 0.001 (0.99) Fractionalization -0.048 (0.46) R-squared 0.434 0.375 0.179 0.132 F-statistic 4.32 (0.00) 11.27 (0.00) 1.01 (0.47) 1.77 (0.20) No. of countries 17 17 11 11 No. of elections 63 63 30 30 p-values computed from robust standard errors are in parentheses. 24 Table 5: Dependent variable: Change in votes of incumbent (Pooled regression: “Mature” vs. “New” Democracies) Mature Democracies New Democracies All variables Econ. Var. All variables Econ. Var. Perceived Corruption Increase -0.519 (0.77) -0.824 (0.57) -2.894 (0.07) -3.393 (0.01) GDP growth 1.001 (0.33) 0.956 (0.24) 3.108 (0.00) 3.651 (0.00) Inflation -1.846 (0.08) -1.961 (0.05) -0.178 (0.07) -0.103 (0.01) Votes incumbent (previous election) -0.034 (0.87) -0.242 (0.46) Years in power -0.067 (0.79) -0.122 (0.78) Party Ideology -0.100 (0.97) 0.477 (0.89) Incumbent seats 0.061 (0.53) -0.175 (0.16) Fractionalization 0.002 (0.97) -0.023 (0.52) R-squared 0.406 0.393 0.521 0.448 F-statistic 0.95 (0.50) 1.82 (0.16) 9.98 (0.00) 25.67 (0.00) No. of countries 14 14 14 14 No. of elections 52 52 41 41 p-values computed from robust standard errors are in parentheses. 25 Table 6: Dependent variable: Change in votes of incumbent (Random effects regression) Parliamentary System Presidential System Mature Democracies New Democracies Perceived Corruption Increase -2.712 (-0.03) -5.080 (0.24) -0.824 (0.66) -3.362 (0.09) GDP growth 2.102 (0.00) 3.051 (0.23) 0.956 (0.34) 3.680 (0.00) Inflation -0.115 (0.03) -0.413 (0.41) -1.961 (0.00) -0.103 (0.30) R-squared 0.375 0.132 0.393 0.448 Wald chi-squared 25.15 (0.00) 2.29 (0.52) 21.98 (0.00) 16.49 (0.00) No. of countries 17 11 14 14 No. of elections 63 30 52 41 p-values are in parentheses. 26