Price undertakings, VERs, and foreign direct investment Jota Ishikawa and Kaz Miyagiwa

advertisement

Price undertakings, VERs, and foreign direct investment#

Jota Ishikawa* and Kaz Miyagiwa**

October 2006

Abstract: We compare the relative effect of a voluntary export restraint (VER) and a price

undertaking on foreign firms’ incentive to engage in FDI. We emphasize foreign rivalry as a

determinant of FDI. We show, in a model that has two foreign firms competing with a home

firm in the home country, that a price undertaking induces more FDI than a VER. The home

country government, operating under the constraint to protect the home firm, is generally better

off settling an antidumping case with a VER than with a price undertaking.

Keywords: Foreign investment, price undertakings, antidumping, voluntary export restraints

JEL code identification: F1

Corresponding author: Kaz Miyagiwa, Department of Economics, Emory University,

Atlanta, GA 30322, U.S.A. E-mail: kmiyagi@emory.edu, Telephone: (404) 7272-6363.

#

We are grateful to Richard Baldwin, Yongmin Chen, Ig Horstmann, and seminar participants at the University of

Colorado, the Graduate Institute of International Studies, and the City University of Hong Kong for helpful

comments. We acknowledge financial support from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and

Technology of Japan under the 21st Century Center of Excellence Project. Jota Ishikawa also wishes to thank the

Japan Economic Research Foundation, and the Japan Securities Scholarship Foundation for financial support.

*

Faculty of Economics, Hitotsubashi University, Kunitachi, Tokyo 186-8601, Japan; jota@econ.hit-u.ac.jp

**

Department of Economics, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.

1. Introduction

Over the last-quarter century, use of antidumping (AD) has spread from a handful of

traditional users (primarily the United States and the European Union) to more than 70

countries (Prusa, 2001). In reality, however, AD petitioners often withdraw their petitions in

favor of direct settlements with exporting firms or governments. For example, during the 198085 period over one-third of U.S. AD petitions were withdrawn in favor of voluntary export

restraints (VERs) resulting from negotiations with foreign governments (Prusa, 1992). During

the same 1980-1985 period nearly half of AD petitions filed in the EU were settled through

price undertakings, which are voluntary price increases offered by foreign firms to offset the

injury to EU producers due to alleged dumping (Messerlin, 1989). More recently, the U.S. and

Canada have also started to settle AD cases through price undertakings. 1

In this paper we examine the relative effect of AD, VERs and price undertakings on

foreign exporters’ incentive to engage in FDI, with special emphasis on foreign rivalry as a

determinant on FDI. There is a large body of literature on “protection-jumping” FDI.2 Much of

this literature adopts an analytical framework in which one foreign firm competes with one

home firm. Such a framework fails to reveal any influence foreign rivalry may have on

incentives to engage in protection-jumping FDI. The objective of this paper is to analyze the

relative effect of price undertakings and VERs on foreign firms’ incentives to locate production

in the home country in the presence of foreign rivalry.

1

This is because, although use of VERs to settle AD cases was prohibited under GATT in 1994 (Agreement on

Safeguards, Article 11) and the existing VERs are to be phased out, price undertakings remain in full compliance

under GATT and WTO rules (Article 8). See Moore (2005) for more institutional backgrounds.

2

See, e.g., Horstmann and Markusen (1987), Motta (1992), Ishikawa (1998), and Blonigen et al. (2004).

2

The literature on price undertakings is small relative to that on VERs. Recent works

include Vandenbussche and Wauthy (2001), Pauwels and Springael (2002), Belderbos,

Vandenbussche, and Veugelers (2004) and Moore (2005). Moore (2005) compares the effect of

price undertakings and VERs in the standard model of differentiated-goods Bertrand duopoly

in the absence of FDI. He finds that a VER leads to a more collusive outcome than a price

undertaking. Belderbos, Vandenbussche, and Veugelers (2004) examine a foreign firm’s

incentive to engage in FDI under an AD duty and a price undertaking, partly motivated by the

aforementioned fact that EU authorities have traditionally preferred to settle AD cases with

price undertakings instead of imposing AD duties. They consider a three-stage game, in which

AD authorities first decide between an AD duty and a price undertaking, the foreign firm then

chooses between exporting and FDI, and finally the foreign competes with the home firm in

prices in the home market. The authors show that AD authorities choose a price undertaking

over an AD duty in order to reduce the foreign firm’s incentive to engage in FDI.

The setting we analyze differs from that of Belderbos, Vandenbussche, and Veugelers

(2004). We examine the relative effect of settling AD cases with price undertakings and VERs

on foreign firms’ incentives to engage in protection-jumping FDI in the presence of foreign

rivalry. To capture foreign rivalry we consider a model in which two foreign firms from the

same foreign country compete with one home firm in the home market. Unlike Belderbos et al.

(2004) we assume Cournot competition. As we show in Section 3, with Cournot competition

an AD duty, a VER and a price undertaking are equivalent in the absence of FDI. Thus, the

assumption of Cournot competition places policy comparisons on neutral grounds by removing

3

any differences among the policy options inherent in Bertrand models, as revealed in Moore

(2005).

The model has two foreign firms first choosing either exporting or engaging in FDI,

and then competing with one home firm in the home market. The analysis offers two main

results. A first is that a price undertaking leads to more FDI than a VER. To understand this

result intuitively, suppose that one foreign firm, under a price undertaking, switches from

exporting to FDI while the other foreign firm chooses to export. Then, no longer subject to the

price undertaking, the investing firm expands output from its local plant, thereby depressing the

price for the exporter. However, since the export price cannot fall under the price undertaking,

the exporter is obliged to curtail exports. Thus, FDI by one foreign firm exerts negative

externalities on the exporting firm, giving each firm an incentive to invest before the other.

With a VER, which is an export quota the foreign government “voluntarily accepts, if

one foreign firm chooses to invest, its quota share is unused and can be redistributed to the

remaining firm, thereby relaxing the quantitative constraint for the exporter. Thus, with a VER,

FDI by one foreign firm gives rise to positive externalities on the exporting firm, diminishing

the incentive to engage in FDI. This difference accounts for our first result that a VER is less

conducive to FDI than a price undertaking.

Our second result concerns importing country welfare. We consider a case in which the

home government settles an AD case through a VER or price undertaking under the political

constraint that the home firm should not be made worse off hurt as a result of the settlement.

This constraint seems realistic, for otherwise the home firm would never withdraw its AD

petition in favor of such a settlement. In such a setting we show that home country welfare is

4

never lower with a VER – and can be higher for particular parameter values – than with a price

undertaking. The explanation comes from our first result. Because a price undertaking is more

conducive to FDI than a VER, and protection-jumping FDI hurts the home firm, the home

country government faces a more stringent constraint with a price undertaking than with a

VER. With a smaller constraint set, a price undertaking is welfare-dominated by a VER.

The reminder of the paper is organized in 7 sections. The next section outlines the

model in more detail. Section 3 establishes the fundamental equivalence among AD duties,

price undertakings, and VERs in the absence of FDI. Sections 4 – 6 study foreign firms’

incentive to engage in FDI under AD, price undertakings, and VERs, respectively. Section 7

compares home country welfare under a price undertaking and a VER. Section 8 concludes.

2. The model setup

To capture foreign rivalry, the focus of our paper, we consider a model in which two

foreign firms from the same country compete with one home firm in the home country market.

Additional assumptions simplify the analysis further. Firstly, all firms are assumed symmetric

and have zero production costs, regardless of location choices foreign firms make, meaning that

FDI offers no production cost advantages to foreign firms. Secondly, FDI requires a fixed setup

cost k > 0. Thus, FDI is never chosen over exporting under free trade. Thirdly, all firms produce

homogenous goods and play a quantity-setting (Cournot) game. As we show in Proposition 1

below, under Cournot competition an AD duty, a VER and a price undertaking are equivalent

in the absence of FDI (we say two policies are equivalent if an equilibrium outcome with one

policy can be duplicated with the other). Cournot competition thus enables us to isolate the

5

relative effect of a VER and a price undertaking on the foreign firms’ incentive to engage in

FDI. It is worth emphasizing here that with just one foreign firm a VER and a price

undertaking are equivalent with or without FDI.3 What drives our result then is the presence of

foreign rivalry.

3. Trade policy without FDI

In this section we compare an AD duty, a price undertaking and a VER in the absence

of FDI. The main purpose is to establish the equivalence among them without FDI. Home

market demand is assumed linear and written

p = a – (x1 + x2 + xh),

where a > 0 and xh denotes the home firm’s output and x1 and x2 the two foreign firms’

outputs.4 As a benchmark, consider the model under free trade. Calculations show that in

equilibrium each firm, foreign and domestic, produces a/4 units of output at the price of a/4,

and makes the per-firm profit a2/16. With total imports at a/2 units, home country welfare, the

sum of consumer surplus and profit to the home firm, equals 11a2/32.

Suppose now that there is an AD duty, t. It can be shown that in equilibrium each

foreign firm produces (a – 2t)/4 and the home firm (a + 2t)/4 units at the price

(1)

3

p(t) = (a + 2t)/4,

Krishna (1989) is the standard reference in the literature exploring the difference between tariffs and quantitative

import restrictions under Bertrand competition. The equivalence between tariffs and quotas for Cournot competition

is due to Hwang and Mai (1988).

4

Following convention, we ignore what might be going on in the foreign country market. It should be noted

however that we could easily introduce the segmented foreign market where the price is higher than in the home

market.

6

with each foreign firm making the profit

(2)

π(t) = (a + 2t)(a – 2t)/16,

and the home firm making

(3)

Π(t) = (a + 2t)2/16.

Consider next a price undertaking, by which the foreign firms agree to maintain their

export prices above the target p. We assume a price undertaking is always binding.5 For any

-

impact on imports, p must exceed the free-trade price, a/4, which we assume. Foreign Firm 1

-

maximizes profit

!1 = (a – x1 – x2 – xh)x1 ,

subject to the constraint p = a – x1 – x2 – xh ≥ p. The best-response function is

-

b1 = max {a – x2 – xh – p, (a – x2 – xh)/2}

-

Interchanging subscripts yields the best-response function for foreign firm 2. The home firm is

not constrained by the price undertaking, and hence its best-response function is the same as

under free trade: bh = (a – x1 – x2)/2. Solving the three-best response functions simultaneously

yields the following symmetric equilibrium export sales per foreign firm

x(p) = (a - 2p)/2

-

-

and the home firm output xh(p) = p. Each foreign firm makes the profit

-

5

-

For example, the European Commission closely monitors the price undertakings and imposes penalties to punish

violators (Pauwels and Springael, 2002).

7

(4)

!(p) = p(a - 2p)/2

-

-

-

and the home firm makes

Π(p) = p2.

(5)

-

-

We now compare an AD duty and a price undertaking that yield the same profit to the

domestic firm. By (3) and (5), Π(t) = Π(p) implies:

-

(6)

p = (a + 2t)/4.

-

A comparison with (1) shows that the price is the same, whether with an AD duty or a price

undertaking. It is easy to check that each firm’s equilibrium outputs remain identical.

Consider now a VER of size v imposed on the volume of exports from the foreign

country:

x1 + x2 ≤ v.

Assume v < a/2 to have any impact on imports, and that each foreign firm exports up to v/2. It

is easy to check that the Nash equilibrium is

(x1, x2, xh) = (v/2, v/2, (a – v)/2).

In equilibrium, industry output is (a + v)/2, and the price is

(7)

p = (a - v)/2;

The profit to each foreign firm is

!(v) = v(a - v)/2.

and that to the home firm is

(8)

Π(v) = (a – v)2/4.

8

We now compare a VER with a price undertaking while keeping the home firm’s profit

constant. By (5) and (8), we then have

(9)

(a – v)/2 = p,

-

or

v = a – 2p.

-

In equilibrium, each foreign firm exports v/2 = (a – 2p)/2, with the home firm producing (a –

-

v)/2 = p. These are the same quantities under the price undertaking p, implying the equivalence

-

-

between a VER and a price undertaking.

We showed that with Cournot competition the three policy options are equivalent in the

absence of FDI. We should point out that the profits to the foreign firms however are higher

with a VER and a price undertaking than with their equivalent AD because foreign firms no

longer pay the duties under these two policies. In the trade literature, these increases in profits

are regarded as inducements for foreign firms to “voluntarily” restrain exports through a price

hike or an export quota. In this paper we call this increase in profit the transfer effect.

We note two facts about the transfer effect. First, the magnitude of the transfer effect is

the same with a VER and a price undertaking, given the equivalence between the two. Second,

due to the transfer effect home country welfare is lower with a price undertaking and a VER

than with an AD duty, given the equivalence.

We restate the main finding of this section in

9

Proposition 1: In the absence of FDI there exists a VER and a price undertaking that are

equivalent to a given AD duty.

For future use we calculate the optimal AD duty. Home country welfare is given by

Wo(t) = (a + 2t)2/16 + t(a – 2t)/2 + (3a – 2t)2/32

where the subscript o denotes the absence of FDI. The first derivative is

W’o(t) = (a + 2t)/4 + (a – 4t)/2 – (3a – 2t)/8

= (3a – 10t)/8,

leading to the optimal tariff to = 3a/10. With a price undertaking the equilibrium consumer

surplus is (a – p)2/2, and the national welfare is

-

Wo(p) = (a – p)2/2 + p2,

-

-

-

where p ≥ a/4. Wo(p) is decreasing at p < a/3 and increasing at p > a/3. Welfare reaches its

-

-

-

-

maximum 3a2/8 at p = a/2, at which imports vanish.

-

4. Anti-dumping and FDI

Suppose that a foreign firm can relocate production to the home country to avoid the

AD duty. Consider a two-stage game, in which the foreign firms simultaneously decide

whether to invest in the home country and then all three firms play a quantity-setting game,

given the location of foreign firms from the first stage. Since the payoffs depend on the location

10

choices of the foreign firms, we first examine all possible second-stage games and then move

back to the first-stage game to examine the foreign firms’ FDI decisions.

If neither foreign firm invests, the equilibrium outcome is the same as is described in

the previous section. If both foreign firms invest, the outcome is the same as that under free

trade, except that the foreign firms’ profits are lower by the investment cost. Thus, we focus on

the third case, in which only one foreign firm invests. In this case, the investing firm has a

lower cost than the exporter. In equilibrium, it produces (a + t)/4 units of output, while the

exporting firm sells (a – 3t)/4 units. The home firm produces the same amount as the investing

firm by symmetry. The equilibrium price is (a + t)/4. The home firm and the investing foreign

firm earns (a + t)2/16 while the exporter makes (a - 3t)2/16. The following matrix presents the

payoffs to the foreign firms, where I denotes investing and E exporting, and first entries are the

profits to the column player:

AD Duty (t)

I

E

I

a2/16 – k, a2/16 – k

(a + t)2/16 – k, (a – 3t)2/16

E

(a – 3t)2/16, (a + t)2/16 – k

(a – 2t)2/16, (a – 2t)2/16.

In the first stage of the game the foreign firms simultaneously choose between I and E.

We make these assumptions:

(i) Simultaneous investments are profitable, or a2/16– k > 0,

(ii) AD duties are never prohibitive, or t < a/3.

11

The equilibrium outcomes are described in the next lemma. (The proofs of this and other

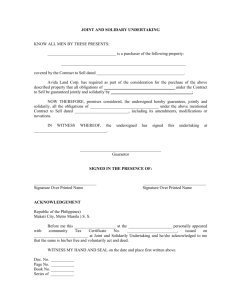

lemmas to follow are found in the Appendix.) Figure 1 illustrates Lemma 1.

Lemma 1. With AD

(A)

(E, E) is the unique equilibrium if k > 3t(2a – t)/16.

(B)

(I, I) is the unique equilibrium if k < 3t(2a – 3t)/16.

(C)

Either (E, I) or (I, E) is the equilibrium if 3t(2a – 3t)/16 < k <3t(2a – t)/16.

5. Price undertakings and FDI

Suppose that (E, E) is the equilibrium outcome with the AD duty, and consider

replacing the duty with the equivalent price undertaking using the formula given earlier:

p = (a + 2t)/4.

-

Given that t < a/3, p ranges over the open interval (a/4, 5a/12). If both foreign firms export,

-

from Section 3 we know that each earns !(p) = p(a - 2p)/2.

-

-

-

When there is FDI, it is convenient to consider the problem in two separate cases,

depending on the AD duty rate.

Case I: a/4 < p < a/3.

-

This corresponds to t ∈ (0, a/6). If both firms invest, each nets the profit a2/16 – k, the freetrade profit less the investment cost. With only one foreign firm investing, the exporter must

choose output xe subject to this constraint:

12

p = a – X – xi – xe ≥ p,

-

where the subscript i (e) denotes the investor (the exporter). With the investor and the domestic

firm facing no such constraints, calculations show that in the symmetric Nash equilibrium

xi = xh = p, and xe = a – 3p < p = xi.

-

- -

As expected, the exporter has fewer sales than the investor. Industry output is

2p + a – 3p = a – p.

-

-

-

The investor and the home firm earn the (gross) profit

!i(p) = p2 = Π(p)

-

-

-

while the exporter earns

!e(p) = p(a – 3p).

-

-

-

Given the range of p, we have !i(p) > !e(p), implying that it is more profitable to be an investor

-

-

-

than an exporter. The table below summarizes the profits to the foreign firms in all secondstage games.

Price undertaking (Case I): a/4 < p < a/3

-

I

E

I

a2/16 – k, a2/16 – k

p2 – k, (a – 3p)p

E

(a – 3p)p, p2 – k

p(a – 2p)/2, p (a – 2p)/2

-- -

-

-

--

-

-

-

13

Lemma 2: With p ∈(a/4, a/3) corresponding to t ∈ (0, a/6)

-

(A)

(I, I) is the unique equilibrium if k < t(a – 3t)/4.

(B)

(E, E) is the unique equilibrium if k > t(a + 2t)/4.

(C)

Either (E, I) or (I, E) is the equilibrium if t(a – 3t)/4 < k < t(a + 2t)/4.

Case II: a/3 < p < 5a/12

-

This case occurs when a/6 < t < a/3. In this case, the targeted price is so high that, when

one foreign firm invests, exports, no matter how small, leads to a violation of the price

undertaking agreement. With the home market foreclosed to exports, the home firm and the

investing foreign firm play a duopoly game, selling a/3 units at the price of a/3 and earning the

profit of a2/9. This leads to the following payoff matrix.

Price undertaking (Case II): a/3 < p < 5a/12

-

I

E

I

a2/16 – k, a2/16 – k

a2/9 – k, 0

E

0, a2/9 – k

p(a – 2p)/2, p (a – 2p)/2

-

-

-

-

Because investment by one foreign firm forecloses the domestic market for exports, there is a

stronger incentive to be a first to invest than in Case I, as seen in the next lemma.

14

Lemma 3: With a price undertaking p ∈(a/3, 5a/12) equivalent to the AD duty t ∈ (a/6, a/3)

-

(A)

(I, I) is the unique equilibrium if k < (7a2 + 36 t2)/144;

(B)

The equilibrium is either (I, I) or (E, E) if k > (7a2 + 36 t2)/144.

(C)

(E, I) and (I, E) are never the equilibrium.

Lemmas 2 and 3 are illustrated in Figure 2. A comparison of Figures 1 and 2 leads to

the next proposition.

Proposition 2: For t < a/6, the price undertaking induces less FDI than the AD duty. For t ≥ a/6

the price undertaking leads to more FDI.

The intuitive understanding of the proposition draws on two effects. First, with AD, an output

expansion by an investing firm causes the export price to fall, forcing export sales to contract.

The price undertaking, however, does not allow the exporter to lower the price. To keep the

price up, the exporter is forced to curtail more exports, thereby making exporting less attractive

relative to FDI with a price undertaking than with an AD duty. FDI decisions however are also

affected by the transfer effect alluded to earlier. With a price undertaking, an exporter no longer

pays an AD duty to access the home market, making exporting relatively a more attractive

choice than FDI. The choice between FDI and exporting depends on which of the two effects is

dominant. For t ≥ a/6 there is no transfer effect under a price undertaking due to market

foreclosure, and hence a price undertaking leads to more FDI. For t ≤ a/6, on the other hand, a

comparison of Figures 1 and 2 shows that the transfer effect is dominant.

15

6. VERs and FDI

In this section we consider the effect of the equivalent VER on FDI. Using (6) and (9),

we obtain the conversion formula:

v = (a – 2t)/2.

Given that t < a/3 we have v ∈ (a/6, a/2). Under a VER agreement the foreign government

allocates the export quota to its national firms equably. If one firm invests and frees itself from

the export quota, that quota share can be redistributed to the remaining exporter. As with a price

undertaking, we consider two cases.

Case I: v ∈ (a/3, a/2).

This case corresponds to t ∈ (0, a/6). If no firm invests, each firm has the quota v/2, leading to

the results obtained in Section 3. If the two firms invest, the VER is irrelevant, and each foreign

firm earns a2/16 – k. Thirdly, if only one firm invests, the entire quota, v, is given to the

exporter. In the present case, since v > a/3 the total quota exceeds the per-firm symmetric

equilibrium output, a/4. Thus, the VER ceases to be binding for the exporting firm, and three

firms compete without facing any quantitative restrictions. Therefore, the equilibrium profits to

the investor and the exporter, respectively, are

!i = a2/16 – k, and !e = a2/16.

We have obtained the following payoff matrix.

16

VER (Case I): v ∈ (a/3, a/2)

I

E

I

a2/16 – k, a2/16 – k

a2/16 – k, a2/16

E

a2/16, a2/16 – k

v(a - v)/2, v(a - v)/2

Obviously, (I, I) is never an equilibrium for any k < a2/16. In fact, we have a stronger result.

Lemma 4: With a VER v ∈ (a/3, a/2) corresponding to t ∈ (0, a/6), (E, E) is the unique

equilibrium.

Turn next to Case II, in which v ∈ (a/6, a/3]. Notice that for v ∈ [a/4, a/3], which

corresponds to t ∈ [a/6, a/4], the VER still becomes unbinding for an exporter when one

foreign firm locates in the home country. We can easily verify that (E, E) is the unique

equilibrium as in Case I.

Consider v ∈ (a/6, a/4), which corresponds to p ∈ (3a/8, 5a/12) or t ∈(a/4, a/3). In this

-

case, if one firm invests under the VER of size v < a/4, the VER becomes binding for the

exporter. It is readily shown that in equilibrium the exporter exports v units while the home

firm and the investing firm produce

xh = xi = (a – v)/3.

In equilibrium industry output is (2a + v)/3 and the price is p = (a – v)/3. The exporter makes

!e(v) = v(a – v)/3, while the investor makes !i(v) = (a – v)2/9. Given the range of v under

17

consideration, we have !i(v) > !e(v), so there is an incentive to invest if the other does not

(provided that k is small). The payoffs from all the second-stage games are shown in the table

below.

VER (Case II): v ∈ (a/6, a/4)

I

E

I

a2/16 – k, a2/16 – k

(a – v)2/9 – k, v(a – v)/3

E

v(a – v)/3, (a – v)2/9 – k

v(a – v)/2, v(a – v)/2

In this game, (I, I) is an equilibrium if

(14)

a2/16 – k ≥ v(a – v)/3

(E, E) is the equilibrium if

(15)

v(a – v)/2 ≥ (a – v)2/9 – k.

Lemma 5: With a VER v ∈ (a/6, a/3) equivalent to the AD duty t ∈(a/6, a/3)

(A)

For v ∈ (a/4, a/3) (E, E) is the unique equilibrium.

(B)

For v ∈ (a/6, a/4) (E, E) is the unique equilibrium if k > (44t2 + 8at +7a2)/72.

(C)

For v ∈ (a/6, a/4) (I, I) is the unique equilibrium if k < (16t2 - a2)/48.

(D)

For v ∈ (a/6, a/4) either (E, E) or (I, I) is the equilibrium if

(16t2 - a2)/48 < k < (44t2 + 8at +7a2)/72.

Lemmas 4 and 5 are illustrated in Figure 3. A comparison of Figures 2 and 3 leads to

18

Proposition 3. A price undertaking leads to more FDI than a VER.

7. Policy implications

In this section we discuss some policy implications of our model. In particular, we

consider the following scenario. The home firm petitions for AD protection but is ready to

withdraw the petition if a price undertaking (or VER) agreement can be worked out with the

foreign firms (or the foreign government). Suppose that with the AD duty the equilibrium

outcome is (E, E), with the home firm earning the profit (a + 2t)2/16. Now, our question can be

stated. Should the home government choose a price undertaking or a VER, if it wants to settle

the AD case under the condition that the home firm is not to be hurt by a settlement? We show

below that the home country is generally better off with a VER than with a price undertaking.

Suppose that the original AD is in Case 1. If the home government is constrained to

stay within the policy ranges of Case 1, a price undertaking and a VER yield the same welfare.

To see this, observe that the equivalent VER leads to (E, E) since it is the equilibrium with the

AD. Furthermore, a tighter VER decreases welfare while a more relaxing VER hurts the home

firm. Thus, the home government has no choice but to settle at the equivalent VER.

With a price undertaking, (E, E), (I, E) and (I, I) are all possible outcomes (compare

Figures 1 and 2), depending on the AD duty and k. (I, I) leads to a smaller profit to the home

firm and is unacceptable as a policy option. With (E, E), the home government cannot do better

than choosing the equivalent price undertaking for the same reason explicated for VERs.

Finally, with (I, E), the price remains at p due to the price undertaking. Thus, the consumer

-

19

surplus is the same as when both foreign firms export and equals (a - p)2/2. The profit to the

-

home firm, at p2 = (a + 2t)2/16, is also the same as when both firms export. Thus, the home

-

country welfare is the same whether we have (I, E) or (E, E). Intuitively, this is because at (I, E)

the exporter must curtail its sales exactly by the same amount as the investor expands its sales,

in order to keep the price at p. Then, if p is raised, welfare falls since Wo(p) is decreasing for p

-

-

-

-

∈ (a/4, a/3) as is recalled from Section 3. On the other hand, lowering p hurts the home firm

-

and is not an acceptable option. So, again, the home government has no choice but to negotiate

a price undertaking at the equivalent level.

To sum up, when the home government’s choice is limited to the policy ranges of Case

1, the home government has no choice but to choose a VER or a price undertaking at the

equivalent levels, both of which lead to (E, E) and yield the same welfare.

Suppose next that the home government can increase protection beyond the policy

range of Case 1. Then, whenever (I, I) is the equilibrium under a VER, it is also the equilibrium

under a price undertaking. Conversely, however, when (I, I) is the equilibrium under a price

undertaking, (E, E) can be an equilibrium under a VER (see Figures 2 and 3). Finally,

whenever (E, E) is the equilibrium with a price undertaking, (E, E) is also the equilibrium under

a VER. What all this means is that the set of parameter values that leads to (E, E) under a price

undertaking is a strict subset of that under a VER.

Further, since the home firm’s profit is smaller with (I, I), the home country

government must choose a policy variable from the sets leading to (E, E). Since the constraint

20

set under a VER is a strict superset of that under a price undertaking, the home government can

do better with a VER than with a price undertaking.

Proposition 4. Suppose that (E, E) is the equilibrium with AD, and that the home country

government is constrained not to hurt the home firm by settling the AD case. Then a VER

(weakly) welfare-dominates a price undertaking.

8. Conclusion

In this paper we examine the foreign firms’ incentives to engage in FDI under a VER

and a price undertaking. We focus on foreign rivalry as a determinant of protection-jumping

FDI, capturing it in a model with two foreign firms from the same country competing in

quantities with a home firm. We find that without FDI, an AD duty, a VER and a price

undertaking are all equivalent in the sense that an equilibrium outcome under one policy can be

duplicated using another. We use that result to show that, when an AD case is settled for an

equivalent policy, FDI is more likely to occur with a price undertaking than with a VER. We

also find that a VER (weakly) welfare-dominates a price undertaking.

Foreign rivalry drives these results. With a price undertaking, investment by one

foreign firm tends to depress the export price and forces the exporter to contract its export sales,

whereas, with a VER, investment by one foreign firm relaxes the export quota confronting the

exporter, provided that the foreign firms originate in the same foreign country. This mechanism

driving our results is likely to be present in a broad class of oligopoly models. For example, in

Bertrand competition, with a price undertaking, investment by one firm would still exert a

21

downward pressure on the export price, while with a VER it relaxes the quota constraint facing

the exporter. Therefore, foreign firms would have more of an incentive to engage in FDI under

a price undertaking than under a VER.

22

Appendix

Lemma 1 Result A is true if both these inequalities hold:

(a - 3t)2/16 > a2/16 – k,

(a – 2t)2/16 > (a + t)2/16 – k

The first is written

16k > 3t(2a – 3t)

and the second is written

16k > 3t(2a – t) > 3t(2a – 3t).

The last inequality implies Result A. Result B is true if both inequalities hold in reverse. If

(a - 3t)2/16 > a2/16 – k,

(a – 2t)2/16 < (a + t)2/16 – k,

then Result C holds.

Lemma 2 Result A is true if both these inequalities hold:

a2/16 – k > (a – 3p)p,

--

p2 – k > p(a – 2p)/2

-

-

-

Using the conversion formula, the first is written

16k < a2 - (a – 6t)(a + 2t) = 4t(a – 3t).

and the second is written

16k < 4t(a + 2t).

23

Since 4t(a – 3t) < 4t(a + 2t), we obtain Result A. Result B is true if both inequalities hold in

reverse. If

a2/16 – k < (a – 3p)p,

--

p2 – k > p(a – 2p)/2,

-

-

-

then Result C holds.

Lemma 3: Result (A) is true if

a2/9 – k > p(a – 2p)/2.

-

-

Using the conversion formula, this is written

k < (7a2 + 36 t2)/144.

If the inequality is reversed, (E, E) also becomes a possible equilibrium outcome. Results (C) is

obvious under the assumption that k < a2/16.

Lemma 4: The lemma is true if

v(a - v)/2 > a2/16 – k.

Since v(a - v)/2 is bounded from below by a2/9 for a/2 > v > a/3, this inequality always holds.

Lemma 5: Result A holds because the proof of Lemma 4 is still valid for a/4 < v < a/2.

Result B is true if both these inequalities hold:

24

v(a - v)/2 > (a - v)2/9 - k

a2/16 – k < v(a - v)/3.

Using the conversion formula, the first is written

k > (44 t2 + 8at - 7a2 )/72

and the second is written

k > (16 t2 - a2 )/48.

Result B follows because (44 t2 + 8at - 7a2 )/72 < (16 t2 - a2 )/48 for a/4 < t < a/3. Result C is

true if both inequalities hold in reverse. Result D is true if

v(a - v)/2 > (a - v)2/9 – k

a2/16 – k > v(a - v)/3.

25

References

Belderos, R., Vandenbuscche, H., and Veugelers, R., 2004. Antidumping duties, undertakings,

and foreign direct investment in the EU. European Economic Review 48, 429-453.

Blonigen, B.A., Tomlin, K., Wilson, W. W., 2004. Tariff-jumping FDI and domestic firms’

profits. Canadian Journal of Economics, 37, 656-677.

Hwang, H., and Mai, C.C., 1988. On the equivalence of tariffs and quotas under duopoly: a

conjectural variation approach, Journal of International Economics 24, 373-380

Horstmann, I. J., and Markusen, J. R., 1987. Strategic investments and the development of

multinationals, International Economic Review 28, 109-121.

Ishikawa, J., 1998. Who benefits from voluntary export restraints? Review of International

Economics 6, 129-141.

Krishna, K., 1989. Trade restrictions as facilitating practices, Journal of International

Economics 26, 251-270.

Messerlin, P., 1989. The EC antidumping regulations: a first economic appraisal, 1980-1985.

Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 125, 563-587.

Moore, M., O., 2005, VERs and price undertakings under the WTO. Review of International

Economics 13, 298-310.

Motta, M., 1992, Multinational firms and the tariff jumping argument: a game theoretical

analysis with some unconventional conclusions. European Economic Review 36, 15571571.

Pauwels, W., and Springael, L., 2002. The welfare effect of a European anti-dumping duty and

price-undertaking policy. Atlantic Economic Journal 30,

26

Prusa, T. J., 1992. Why are so many antidumping petitions withdrawn? Journal of International

Economics 33, 1-20.

Prusa, T. J., 2001. On the spread and impact of anti-dumping. Canadian Journal of Economics

34, 591-611.

Vandenbuscche, H., and Wauthy, X., 2001. Inflicting injury through product quality: how

European antidumping policy disadvantages European producers. European Journal of

Political Economy 17, 101-116.

27

k

(E, I), (I, E)

a2/16

a2/18

(E, E)

(I, I)

t

a/6

a/3

Figure 1: Equilibrium outcomes under AD

28

(I, I), (E, E)

k

a2/16

a2/18

(E, E)

(I, I)

a2/48

t

(E, I), (I, E)

a/6

a/3

Figure 2: Equilibrium outcomes under price undertakings

29

k

a2/16

(E, E)

(E, E), (I, I)

(I, I)

t

a/4

a/3

Figure 3: Equilibrium outcomes under VERs