A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NATIVE AMERICAN STUDENT ACADEMIC

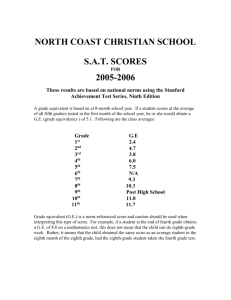

advertisement