OCTOBER TERM, 2007 1 Syllabus

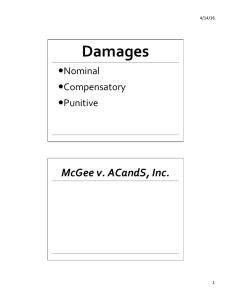

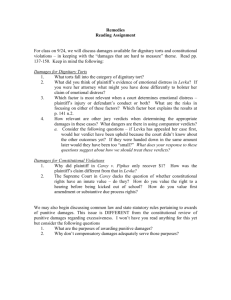

advertisement