4/3/2016 Stuttering in preschoolers: Multifactorial perspective on its nature, assessment and treatment

advertisement

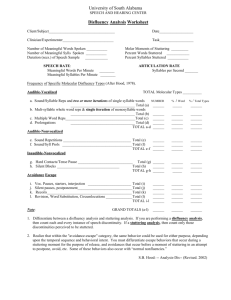

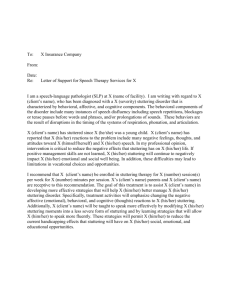

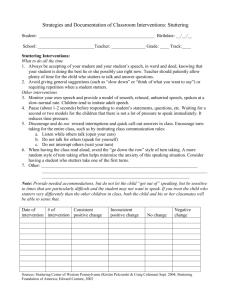

4/3/2016 Stuttering in preschoolers: Multifactorial perspective on its nature, assessment and treatment Victoria Tumanova, Ph.D., CF-SLP Assistant professor, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Syracuse University vtumanov@syr.edu Iowa Conference on Communication Disorders April 8, 2016 Overview of the talk • 1st hour • Nature of developmental stuttering • Normal disfluency and onset of stuttering in preschoolers • Spontaneous recovery and its predictors • 2nd hour • Constitutional, developmental, environmental and learning factors in stuttering development • 3rd hour • Assessment of stuttering following the multifactorial perspective • 4th hour • Treatment approaches for preschool-age children What is stuttering? • It is an observable behavior (E) • Disfluency and Stuttering reflect a disruption in the smooth transitioning between sounds, syllables , and words. • It is a disorder of communication 1 4/3/2016 What are STUTTERING behaviors? • BETWEEN-WORD disfluencies • Interjections • Revisions • Phrase repetitions • WITHIN-WORD disfluencies Within-word disfluencies (1) Sound/syllable repetitions (2) Single-syllable whole word repetitions (3) Disrhythmic phonation sound prolongations broken words blocks (silent prolongations) STUTTERING IS A FORM OF SPEECH DISFLUENCY CHARACTERIZED BY A RELATIVELY HIGH PROPORTION OF WITHIN-WORD SPEECH DISFLUENCIES AND ASSOCIATED BEHAVIORS 2 4/3/2016 Core behaviors of stuttering • Basic speech behaviors (=within-word disfluencies) • Repetitions • Prolongations • Silent blocks • They are involuntary • They are out of the PWS’s control • Loss of control • Helplessness • Characterizes stuttering as opposed to normally disfluent speech Secondary Behaviors • Reactions to core behaviors • Attempt to end or avoid stuttering • Are learned patterns • Escape and avoidance Normal Disfluency and the Development of Stuttering 3 4/3/2016 ONSET OF STUTTERING: THE FACTS • Onset of stuttering typically between 2-4 years of age • Probability of stuttering onset decreases with age • Lifetime incidence (in USA and Western Europe) approximately 4-5% of the population • Incidence is an index of how many people have stuttered at some time in their lives • Prevalence ranges from 0.5% to 1% • Prevalence indicates how wide-spread the disorder is (how many people currently stutter) • Higher prevalence in preschool-age children • Lower prevalence in older children and adults Yairi and Ambrose 2005 • “Early childhood stuttering” book • Gathered longitudinal data on 146 CWS and 59 CWNS • Onset • Sudden 40% • Intermediate (over 1-2 weeks) 30% • Gradual (3 or more weeks) 27% • First disfluencies • Only 35% of parents described their child’s disfluencies as easy repetitions • More iterations per instance of repetition • Rapid rate of iterations • Disfluency clusters Johnson et al., 1959. The Onset of Stuttering Disfluency types (at onset) of children thought to be normally disfluent versus children thought to be stuttering 4 4/3/2016 Tumanova et al. 2014 study • Parental concern and frequency of disfluency for preschool-age children • When do parents become concerned about their child’s fluency? • 399 children 3-5:11 y/o and their parents participated • Overall frequency of disfluencies in CWS and CWNS • How disfluent are preschool-age children? • 472 children 3-5:11 y/o participated Tumanova, V., Conture, E. G., Lambert, E. W., & Walden, T. A. (2014). Speech disfluencies of preschool-age children who do and do not stutter. Journal of communication disorders, 49, 25-41. Parental Concern about Stuttering • 399 children 3-5:11 y/o participated • Parents of 221 children were concerned • 164 boys, 57 girls, mean age = 49 months • average of 8.53% stuttered disfluencies • average of 3.51% normal/other disfluencies • Parents of 178 children were NOT concerned • 93 boys, 85 girls, mean age = 50 months • average of 1.44% stuttered disfluencies • average of 2.87% normal/other disfluencies Tumanova, V., Conture, E. G., Lambert, E. W., & Walden, T. A. (2014). Speech disfluencies of preschool-age children who do and do not stutter. Journal of communication disorders, 49, 25-41. Stuttered Disfluencies per 100 words 5 4/3/2016 Normal/Other Disfluencies per 100 words Criteria for Stuttering Diagnosis • We begin to suspect that a child is either stuttering or at risk for developing a stuttering problem if (s)he meets BOTH of the following criteria • Produces THREE or more WITHIN-WORD speech disfluencies per 100 words of conversational speech (i.e., sound/syllable repetitions and/or sound prolongations) • Parents and/or other people in the child’s environment express concern that the child stutters. Stuttering as a disorder: Etiology (implications for treatment) • So FAR… • Stuttering as a behavior 6 4/3/2016 Overview Nature interacting with nurture (from Conture, 2001): If a disorder thought to be the result of a combination of genetic and environ mental influences, its etiology can be referred to as multifactorial Example of an Interaction between environment (salt) and person (finger) making a weakness or difficulty more pronounced Constitutional Factors: Genes • Stuttering often runs in families • 30 to 60% of PWS have family histories of stuttering • Research is underway to identify genes associated with stuttering • Single gene for transient stuttering; two or more genes for chronic stuttering • Twin studies, adoption studies provide evidence that environmental factors are also important • Twin studies show that whether stuttering occurs is 2/3 genetics and 1/3 environment 7 4/3/2016 Clinical Implications • Parents should be told that stuttering is often inherited, not a result of bad parenting • SLPs can’t change a child’s genes but they can help modify this child’s environment Constitutional Factors: Brain Structure and Function • PWS have less dense white matter tracts in the area of left operculum (tracts that are thought to connect sensory, planning and motor areas of the brain) (Sommer et al., 2002) • White matter neuroanatomical differences have been reported in CWS as well (Chang et al., 2015) • Brain areas used for sensory integration are not efficiently connected to motor planning and motor execution areas www.humanconnectomeproject.org Constitutional Factors: Brain Structure and Function • Meta-analysis by Brown et al., 2005 • Overactivation in right hemisphere areas that are homologous to left hemisphere areas active for speech production • Overactivation in left hemisphere areas related to motor control of speech • Deactivation of left auditory cortex during stuttering 8 4/3/2016 Sensory and Sensory-Motor Factors • PWS are slower in initiating a movement • PWS are more variable • Slower reaction times • Slower on nonspeech sequencing • Slower at tapping at a comfortable rate, but faster and more variable at a fast rate • PWS show lower accuracy when performing auditory tasks • Poorer at auditory-motor tracking • Weaker-than-normal vocal adjustments to perturbations during sustained vocalization (Loucks, Chon & Han, 2012) • Masking and other changes in auditory feedback decrease stuttering Clinical Implications • Evidence that treatment changes neurological function • May suggest that treatments restore effective sensorymotor control of speech • Because PWS process more slowly, slower speech may facilitate fluency • Because of sensory processing deficits, masking, DAF, attention to kinesthetic feedback may be helpful in treatment Constitutional Factors: Emotion and Temperament • Emotion may increase stuttering, and stuttering may increase emotion • Important findings • PWS are not more anxious than PWNS, but more anxiety produces more stuttering • Autonomic arousal associated with stuttering • PWS may have more inhibited temperaments; may be more emotionally conditionable • Emotional processes: • CWS less adaptable to novelty than CWNS • CWS more emotionally reactive, less emotionally and attentionally regulated • Emotions interacting with speech-language planning and production: • CWS as apt to stutter during/after positive as negative arousal 9 4/3/2016 Emotional Development in CWS • Less adaptability to novelty, change and differences (Anderson, Pellowski, Conture & Kelly, 2003), • Lower inhibitory control and attention shifting as well as significantly greater anger/frustration, approach and motor activation (Eggers, De Nil, & Van den Bergh, 2010); • Greater emotional reactivity and lesser emotion regulation (Karrass, Walden, Conture, Graham, Arnold, Hartfield, et al., 2006), • More reactivity to environmental stimuli (Wakaba, 1998). Behavioral inhibition • Behavioral inhibition refers to a pattern of behavior involving withdrawal, avoidance, and fear of the unfamiliar. • CWS are more apt to exhibit BI. There were significantly more CWS in the high BI group and fewer CWS in low BI group compared to CWNS. • More behaviorally inhibited CWS, when compared to less behaviorally inhibited CWS, exhibited more stuttering. Choi, Conture, Walden, Lambert, & Tumanova (2013). Behavioral inhibition and childhood stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders. Developmental Factors: Speech and Language • Stuttering seems to have its most frequent onset when the child is mastering more complex language • Rapid speech and language development may stress “weak” areas, resulting in stuttering • We know already that stuttering as a behavior occurs in longer more complex utterances (=complex language) • Do Children who Stutter show weaker linguistic skills and knowledge than their normally-fluent peers? 10 4/3/2016 Language Development • Ntourou, Conture, & Lipsey (2011). Meta-analysis of language contributions to childhood stuttering. American Journal of SpeechLanguage Pathology, 20, 163-179. • CWS scored significantly lower than CWNS on global normreferenced measures of language development, receptive and expressive vocabulary, and mean length of utterance (MLU). Language Development 32 Co-occurring Disorders • No group differences on articulation test, GFTA, (Clark et al, 2014) • Preschool-age children (3-6 y/o) • Stuttering frequently coincides with articulation and/or phonological disorder (Blood, Ridenour, Qualls & Hammer, 2003) • About 30% of CWS exhibit mild-severe phonological delays/disorders • School-age children 11 4/3/2016 Linguistic Dissociations • Children who stutter (36%) exhibit significantly more dissociations or asynchrony within and between subcomponents of their linguistic formulation processes than children who do not stutter (18%) • Dissociation = [a] performance of two subcomponents fall into 5% of the population + [b] the two subcomponents must be separated by at least one standard deviation. • Possible explanation: Poor “goodness-of-fit” among (sub)components of linguistic processing system. This incongruence between components of speech-language system places strain on speech-language system, resulting in less fluent speech as more time and energy is devoted to linguistic formulation processes. Take-home message • Even when both CWS and CWNS are within normal limits • CWS syntactic, semantic and phonological processes slower than CWNS • CWS exhibit more “unevenness” in the development of language, vocabulary and articulatory skills than CWNS Speech-Language Production Semantics Anderson, J. D., Pellowski, M. W., & Conture, E. G. (2005). Childhood stuttering and dissociations across linguistic domains. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 30(3), 219-253. Phonology Syntax Developmental Factors: Cognitive Development • Intensive cognitive development may compete with fluency • The “ups” and “downs” in a child’s fluency may reflect spurts of cognitive development • After age 3, children may be self-conscious enough to have negative emotions about stuttering 12 4/3/2016 The Young Child's Awareness of StutteringLike Disfluency Ezrati-Vinacour, Platzky, & Yairi (2001) • Normally fluent preschool and first-grade children watched videos of two puppets speaking fluently and disfluently • Which one speaks like you? • Whose speech do you like better? Results • It was found that from age 3, children show evidence of awareness of disfluency, but most children reached full awareness at age 5. • Negative evaluation of disfluent speech is observed from age 4. Awareness of Stuttering in preschoolers • Clark, Conture, Frankel, and Walden (2012). Communicative and psychological dimensions of the KiddyCAT. Journal of Communication Disorders • Preschool-age (3-5:11) CWS had more negative attitudes towards their own speech than CWNS regardless of age or gender. Additionally, analysis indicated that one dimension— speech difficulty—appears to underlie the KiddyCAT items. Developmental Factors: Social and Emotional Development • Emotional arousal increases stuttering and normal disfluency • Emotional stress during childhood may trigger or worsen stuttering • Some children who stutter—because of a sensitive temperament—may be more vulnerable to normal stresses of childhood • Individuals who stutter appear to be normal in terms of psychosocial traits 13 4/3/2016 Developmental Factors: Summary Speech and Language Processes: • Even when both CWS and CWNS are within normal limits… • CWS’s syntactic, semantic and phonological processes are slower than those of CWNS • CWS exhibit more “unevenness” in the development of language, vocabulary and articulatory skills than CWNS Emotional processes: • CWS are less distractible, less adaptable to novelty than CWNS • CWS are more emotionally reactive, less able to regulate their emotion and attention Interaction between Emotional and Speech-language processes: • CWS are apt to stutter during/after positive as well as negative arousal CWS speech planning and production systems are less well developed, probably more vulnerable to interference, particularly emotional/cognitive interference. Also, emotional reactivity may not be well regulated in CWS. Environmental factors may interact with developmental factors to trigger or worsen stuttering HELP WANTED Speech and Language Environment • Research unclear: Do families of kids who stutter have stressful speech and language models? • Speculation about some variables causing stress for vulnerable children: Possible Speech and Language Stresses Stressful Adult Speech Models Rapid speech rate Complex syntax Polysyllabic vocabulary Use of two languages in home Stressful Speaking Situations for Children Competition for speaking Hurried when speaking Frequent interruptions Frequent questions Demand for display speech Excited when speaking Loss of listener attention Many things to say 14 4/3/2016 Clinical Implications • Children who stutter may be helped by making communication easier. • More one-on-one time when parent can listen • Slower speech rate • Language complexity not too far above child’s level Environmental factors: Life Events Stressful life events may precipitate or worsen stuttering in some children Stressful Life Events That May Increase a Child’s Disfluency The child’s family moves to a new house, a new neighborhood or a new city. The child’s parents separate or divorce. A family member dies. A family member is hospitalized. The child is hospitalized. A parent loses his or her job. An additional person comes to live in the house. One or both parents go away frequently or for a long period of time. Holidays or visits occur which cause a change in routine, excitement, or anxiety. A discipline problem involving the child. The Facts about Stuttering Imply the Following • Stuttering is an inherited disorder • It first appears when children are learning the complex coordination of spoken language • It emerges in those children whose speech production system is vulnerable to disruption by competing demands of language, cognition, and emotion • After it emerges, it becomes persistent in some children – perhaps those whose stuttering arouses substantial negative emotion which leads to a variety of learned behaviors 15 4/3/2016 LEARNING FACTORS • Learning is a process leading to changes in a person/animal as a result of their experiences • Learning does NOT have to be • Conscious • “Correct”, “good for you” or adaptive • Any overt or behaviorally apparent act • Types of learning • Classical conditioning (Ivan Pavlov) • Operant conditioning (B.F. Skinner) • Avoidance conditioning Assessment: Multifactorial perspective Stuttering as a Multifactorial, Dynamic Disorder • Anne Smith and her colleagues (e.g., Smith & Kelly, 1997) suggest there is no one cause of stuttering, but an array of factors contributing to it • The problem is to find the relevant factors and discover how they interact • They see stuttering as “dynamic” because behaviors (repetitions, prolongations, blocks) are only surface features of an ever-changing process • Examples of the underlying factors are linguistic load, speech motor instability, emotional stress, etc. 16 4/3/2016 Multifactorial Perspective Smith & Kelly, 1997 Subgroups • “stuttering recipe” • for each individual, the factors may be different and in different amounts… • while there is evidence that subgroups exist among CWS, not every person is a “subgroup” Healey, Scott Trautman, and Susca, (2004). Clinical applications of a multidimensional approach for the assessment and treatment of stuttering. CICSD, 31, 40-48 Questions for Preschool-age Child Diagnosis • Is the child stuttering or at risk for stuttering? • Will the child spontaneously recover/ “outgrow” stuttering? • How high is the need for and desirability of therapy? • What should be the initial focus of therapy? 17 4/3/2016 Assessment: Caregiver Interview Interview the parents • When was the problem first noticed? How old was the child? • Who noticed the problem? What did he/she do? • What was the speech like? How has it changed since? • Do you see consistent amount of disfluency or does it vary from day to day? • Do you have a family history of stuttering? • What do you and others do when the child stutters? Why do you do it? Does it help? Caregiver Interview • Case history • • • • • Gender Age of onset Time since onset Family history of stuttering Caregiver concern • Child temperament 18 4/3/2016 Gender • 2:1 male-to-female ratio among very young children (3 yrs) close to the onset of stuttering (Yairi & Ambrose, 2013; Mansson, 2000 and others) • However, girls recover more frequently so that by the time children are of school age, the ratio becomes 3 boys to 1 girl who stutters and continues at a 3:1 ratio • More boys than girls develop chronic stuttering problems (3:1) Age of Onset • Onset of stuttering typically between 2-4 years of age • Probability of stuttering onset decreases with age • Age of onset is not currently a prognostic indicator • Yairi & Ambrose (2005) reported a large overlap in the age of onset between persistent and recovered CWS. • Some longitudinal findings show that recovered CWS start stuttering 5 to 8 months earlier than persistent (Watkins & Yairi, 1997) Time Since Onset of Stuttering • Research data shows that a large percentage of CWS recover without treatment • Estimates of unassisted recovery or remission range from 32%-80% • Best estimate is 75% • Probability of recovery highest from 6-12 months post onset • Majority of children recover within 12-24 months post onset Yairi and Ambrose 2005 book 19 4/3/2016 Patterns of Recovery • Period of recovery marked by steady decrease in sound/syllable and word repetitions and prolonged sounds over time, beginning shortly after onset • Subgroup of children presenting with “severe” stuttering at onset, with frequency of behaviors peaking at 2-3 months post onset and full recovery seen by 6-12 months Yairi and Ambrose 2005 book Severity Rating Scale for Parents of Preschoolers • Used in Lidcombe Program (Onslow, Costa & Rue, 1990) • Parents mark an “x” in relevant box at end of each day to indicate severity of stuttering for day • Weekly charts are used by parents and clinical to assess child’s progress • Evidence for its reliability and validity * * * * * * * Family History of Stuttering • Stuttering has been shown to run in families (e.g., Reilly et al., 2009). • Yairi and Ambrose (1992) found that 66.3% of preschool-age children who stutter (CWS) had a positive family history for stuttering. • Mansson (2000) found that 67% of persistent CWS had a familial background of stuttering. 20 4/3/2016 Family History of Stuttering • 198 preschool-age children who do (82 CWS; 67 boys, 15 girls) and do not stutter (116 CWNS; 61 boys, 55 girls) and their parents enrolled in the study • 4 visits spaced out 8 months apart across 2 years • Of the above 112 participants who completed three or more visits, 88 (78%) had caregivers who consistently reported a family history of stuttering (whether present or absent) across the three visits. Thus, the final sample included 88 children and their caregivers. Tumanova, V., Choi, D., Clark, C., Conture, E. G., & Walden, T. A. (in preparation). Family history, gender and stuttering chronicity. Family History and Gender There was a marginally greater likelihood to have a positive family history of stuttering for CWS than CWNS There was no sig. gender ratio difference between CWS with and CWS without a family history of stuttering Family History and Caregiver Concern Higher TOCS-SFR scores were given by caregivers who reported a FH of stuttering, regardless of whether their children were diagnosed CWS or CWNS TOCS-DRC scores were marginally lower for parents of CWNS with a negative family history compared to all other parents 21 4/3/2016 Family History and Recovery from Stuttering • Recovery from stuttering was not significantly different between CWS with a positive versus CWS with a negative family history of stuttering • For children who stuttered at the initial visit, neither gender (p=.522), family history (p=.122), nor interactions between gender and family history (p=.484) significantly predicted their recovery status at the two year follow-up visit. Caregiver concern for stuttering • Data shows it is associated with frequency of stuttering • What are the ways to assess it objectively? Tumanova, V., Conture, E. G., Lambert, E. W., & Walden, T. A. (2014). Speech disfluencies of preschool-age children who do and do not stutter. Journal of communication disorders, 49, 25-41. Test of Childhood Stuttering Gillam, Logan & Pearson, 2009 • Designed for children between the ages of 4 and 12 years • Consists of three subparts • Speech fluency measure made in several different linguistic contexts • • • • Rapid picture naming (40 pictures) Modelled sentences (produce a sentence using the clinician’s model) Structured conversation (answer questions about a series of 8 pictures) Narration (children tell a story based on the pictures used in structured conversation) • Observational rating scales (can be filled out by clinician, teacher, caregiver) • Supplemental clinical assessment used for a more detailed analysis of child’s stuttering • Disfluency duration • Speech rate • Number of iterations per repetition • Shown to have good validity and reliability 22 4/3/2016 Test of Childhood Stuttering Observational rating scales 183 children and their parents participated. Parents of 90 children were concerned about stuttering (CWS; 25 girls; 65 boys) Average score of 15.34 on TOCS 1 Average score of 6.12 on TOCS 2 Parents of 93 children were NOT concerned (CWNS; 43 girls; 50 boys). Average score of 2.2 on TOCS 1 Average score of 2.2 on TOCS 2 Tumanova, V., Choi, D., Conture, E. G., & Walden, T. A. (in preparation). TOCS, MLU and stuttering evaluation for preschoolage children Findings TOCS Speech Fluency 0 1 TOCS Disfluency Consequences 0 1 “Concerned” parents exhibited significantly higher scores on TOCS speech fluency rating scale (p<.0001) and TOCS disfluency related consequences scale (p<.0001) than parents of CWNS. Children whose parents gave a higher score on TOCS speech fluency scale stuttered more during evaluation. Temperament • Ambrose, Yairi, Loucks, et al. (2015) reported among other differences (lower performance on standardized tests of language) • CWS with persistent stuttering were judged by their parents to be more negative in temperament • Assessment Measures • Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001) • Behavior Style Questionnaire (BSQ, McDevitt & Carey, 1978) 23 4/3/2016 Assessment: Child Assessment Components Child Assessment Components • Measures obtained from speech samples • • • • • Disfluency Count Types of disfluencies Duration of disfluencies Speech rate Mean length of utterance • Standardized measures of speech and language • Articulation • Receptive and Expressive Language • Children’s speech-associated attitudes and awareness Healey, Scott Trautman, and Susca, (2004). Clinical applications of a multidimensional approach for the assessment and treatment of stuttering. CICSD, 31, 40-48 24 4/3/2016 Parent-child interaction • Done first to get unbiased sample • Opportunity to observe child’s stuttering and awareness of it • Opportunity to observe parent’s style of interacting with child • Average speech rate for child and parent • Video record for later analysis Motor Component • Frequency • Type • Duration • Severity • Secondary behaviors • Overall Speech Motor Control Speech Sample • For assessment, attain two samples: one in clinic and one outside • Outside samples • Preschoolers: at home • School-age: in school • Adolescents and adults: at work or in a phone conversation • Because stuttering is variable, ensure that sample is representative of current level of stuttering • Videotaping is important for major samples • Samples must be long enough to get representative sampling of speech • For major assessments, use 300-400 syllables for conversation and 200 for reading • For reading sample, ensure passage is at or below client’s level 25 4/3/2016 Assessing Frequency of Stuttering Behaviors • Percentage syllables stuttered (%SS) (SSI-3 and 4) • %SS = total stuttered disfluencies/total syllables • Percentage of words stuttered (%SW) • %SW = total stuttered disfluencies/total words • When counting stutters, each syllable can only be stuttered once (ex. N-n-n-n-n-nuh-nuh…[silent block]…name” = one stutter) • If client has obvious avoidance behavior without stutter, may count as stutter (ex. “My name is uh…uh…uh…uh…Ben”) Yaruss, J. S. (2001). Converting between word and syllable counts in children's conversational speech samples. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 25(4), 305-316. Assessing Types of Disfluencies • Important in distinguishing normally disfluent children from those who stutter • Stuttered versus normal disfluencies • Stuttered = part-word and single-syllable whole-word repetitions, tense pauses, and dysrhythmic phonations • Normal = multisyllabic word repetitions, phrase repetitions, interjections, and revisions • If child has more than 3 stuttered disfluencies per 100 words, more likely to be stuttering (=stuttering diagnostic criteria) • If child has more than 10% of total disfluencies more likely to be stuttering • If stuttered disfluencies comprise 50% or more of all child’s disfluencies, more likely to be stuttering than normally disfluent • Sometimes normal disfluencies can become stuttered (“uhm-uhm-uhm”) Assessing Duration • Common practice to average duration of three longest stutters • This is a component of severity assessment • Use stopwatch to measure duration (to nearest one-half second of longer stutters in sample). Average longest three. • The SSI-4 26 4/3/2016 Online vs. Offline • Online diagnostic assessment = real-time analysis (Yaruss, 1998) • Offline diagnostic assessment = transcript based assessment (i.e., SALT) • Provide a measure of the frequency of various types of disfluency occurring in a speech sample. • Does not require a transcription. • Provides information important to clinical decision-making. • Transcribed analysis is time consuming and Real-Time Analysis can be done more frequently, thus is a better tool for session-to-session documentation. Online analysis: (Yaruss, 1998) • Begin coding speech with a dash (-) for fluent words and an (x) or coding symbol for a disfluent word. • Coding Symbols used: • • • • • • • SSR = sound/syllable repetitions WWR = single syllable whole word repetition ASP = audible sound prolongations ISP = inaudible sound prolongations INT = interjection REV = revision PR = phrase repetitions • Representative Sample. Do not worry about missing words or maintaining pace with the speaker. Focus on obtaining a representative sample. • Intra-judge agreement is important. Frequency: % Total Words Disfluent (% TD) = 38/300*100 = 12.67% % Total Words Stuttered (%SLD) = 36/300*100 = 12% • % SLD/TD= 36/38*100 = 94.74% • Sound prolongation Index = 14/36*100 = 38.89 % • • Duration: • Average Duration of 3 longest SLDs = (2.78+2.64+2.10)/3 = 2.51 seconds 27 4/3/2016 Assessing Secondary Behaviors • Major division = escape versus avoidance behaviors • Escape behaviors occur after stutter has started. They are an attempt to stop stutter and produce a word (ex. Head nod, eye blink) • Avoidance behaviors occur before stutter has begun. They are attempts to keep from stuttering (ex. Saying extra sound, changing word) • Severity assessments often include measure of secondary behaviors • Preschoolers who stutter close to onset have been reported to have face and head movements (Yairi, Ambrose, & Niermann, 1993; Kelly & Conture, 1991). Assessing Severity • Assessment of severity is a clinically relevant measure because it captures what listeners experience • Good for measuring progress in treatments that reduce abnormality of stuttering but don’t eliminate stuttering altogether • Three instruments to assess severity • Stuttering Severity Instrument-3 or 4 • Severity Rating Scale for parents of preschoolers • Test of Childhood Stuttering Severity Rating Scale for Parents of Preschoolers • Used in Lidcombe Program (Onslow, Costa & Rue, 1990) • Parents mark an “x” in relevant box at end of each day to indicate severity of stuttering for day • Weekly charts are used by parents and clinical to assess child’s progress • Evidence for its reliability and validity * * * * * * * 28 4/3/2016 Assessing Speaking Rate • Speaking rate vs. articulatory rate • Only count syllables/words that convey information • Severe stutterers may produce speech at a very slow rate, decreasing their communicative effectiveness • Individuals who both stutter and clutter may have excessively fast rates of speech, making them somewhat unintelligible Linguistic Component • Overall assessment of speaker’s language skills and abilities • Language formulation demands and their effect of stuttering • Stoker Probe • Conversational speech sample • Narrative speech sample • Mean Length of Utterance Children’s speech-associated attitudes and awareness • Preschool Children • KiddyCAT (Vanryckeghem & Brutten, 2002) • Impact of Stuttering on Preschoolers and Parents (Langevin, Packman, & Onslow.(2010). Journal of Communication Disorders, 43, 407-423) 29 4/3/2016 Social Component • Client’s communicative competence • Reactions to various communicative situations • Reactions to various communicative partners • Any avoidances of speaking situations • Any teasing as a result of stuttering • Pragmatic aspect of communication Tools to Assess Social Component • Take information re: social component from questionnaires assessing feelings and attitudes • Observe client interact with different listeners/in different speaking situations (home/school/clinic) • During the assessment • By asking parents/teachers for information Cognitive Component • Thoughts and Perceptions • Negative view on their own stuttering • Negative view on listener’s reactions • Awareness and understanding of stuttering • • • • Is client aware that he/she stutters Can client identify moments of stuttering Why do you stutter – client’s theory How do you stutter – describe/show the SLP • Theory of therapeutic change 30 4/3/2016 Treatment for preschoolers Treatment options – none, waiting, indirect, direct? • Review risk factors specific to your preschool client • Factors that may be associated with persistence of stuttering: • • • • • • Stuttering does not decrease during 12 months after onset CWS is a male Relatives who have not recovered from stuttering Co-existing speech-language disorders Below-average nonverbal intelligence scores Sensitive temperament Spontaneous Recovery Predictors • Onset before age 3 • Female • Measurable decrease in sound/syllable and word repetitions, and sound prolongations, overtime, observed relatively soon (6-12 mos) post-onset • No coexisting phonological problems (and possibly language and cognitive problems) • No family history of stuttering or a family history of recovery from stuttering • ***All are probability indicators*** Yairi and Ambrose 2005 book 31 4/3/2016 Recommendations for Child with Typical Disfluency • Give information about normal disfluency • If parents are concerned, set up another appointment in several weeks to reevaluate if disfluency persists or worsens • If needed, recommend changes in environment that may help all children: e.g., turn-taking, careful listening, appropriate speech rates Recommendations for Child with Borderline/Beginning Stuttering • Use risk factors and duration of stuttering since onset and awareness of stuttering to determine if treatment should be direct or indirect • Teach parents to use severity rating (SR) scale and have them begin to use it • Borderline (usually younger preschool children): • • • • • Discuss with parents option of indirect treatment or watchful waiting Provide online resources e.g. Stuttering and the Preschool Child (Stuttering Foundation) http://www.stutteringhelp.org/content/parents-pre-schoolers (E) Have parents share weekly results of SR scale Treatment Goals • Speech behaviors targeted for therapy • Aspects of family’s speech and nonspeech behaviors • Fluency goals • Spontaneous fluency • Feelings and attitudes • Work with family’s feelings, behaviors, and attitudes to keep the child feeling positive about speech • Maintenance Procedures • Keep contact with family even after child has achieved fluency; gradually taper off, remaining open to future contact if needed 32 4/3/2016 Indirect treatment • “Indirect” means that the child’s stuttering as well as their general speaking abilities are NOT directly addressed. • The focus is on adjusting the contexts in which communication occurs to facilitate fluency. • This type of therapy typically implemented first for children who are likely to recover from stuttering Indirect therapy • Assess parental models during interactions with their children • Turn taking; pausing, interrupting, eye contact, rate of speech, complexity of child-directed speech/language, frequency of questioning • Parents identify situations/behaviors by child and others that elicit more stuttering • Child’s own speaking patterns are analyzed to focus on stuttering Indirect therapy • Results of the assessment of parent-child interactions are then used to identify behaviors to target in treatment • Therapy typically involves sporadic sessions (initial 2-3 sessions, then monthly visits, bimonthly, annual etc.) • Often therapy is delivered in a group setting • Parent group • Children’s group Parent reduces “time pressure” in daily routine, and “communicative time pressure” in verbal interaction with child 33 4/3/2016 Treatment approaches that use this method • Family-focused treatment • Yaruss, J. S., Coleman, C., & Hammer, D. (2006). Treating preschool children who stutter: Description and preliminary evaluation of a family-focused treatment approach.Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(2), 118-136. • Demands and Capacities Model treatment • Franken, M. C. J., Kielstra-Van der Schalk, C. J., & Boelens, H. (2005). Experimental treatment of early stuttering: A preliminary study. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 30(3), 189-199. • Palin Parent-Child Interaction Therapy • Millard, S. K., Nicholas, A., & Cook, F. M. (2008). Is parent–child interaction therapy effective in reducing stuttering? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(3), 636-650. • Stuttering Prevention and Early Intervention treatment • Gottwald, S. & Starkweather, C. (1995). Fluency intervention for preschoolers and their families. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 11, 117-126. Working with Aspects of Parent-Child Interaction • Examples of typical family interaction patterns that may stress a vulnerable child (E) • High rates of speech • Rapid-fire conversational pace (lack of pauses between speakers) • Interruptions • Frequent open-ended questions • Many critical or corrective comments • Inadequate or inconsistent listening to what the child says • Vocabulary far above the child’s level • Advanced levels of syntax Working with Aspects of Parent-Child Interaction • To help parents develop more fluency-facilitating interactions, clinician can model for parent, and then have parent try new behaviors with clinician observing and giving feedback (E) 34 4/3/2016 One-on-One Time with Child • Parent should try to arrange 10-15 minutes per day of one-on-one time with child to practice parent-child interaction changes • Best done at same time each day so child can look forward to it • Major characteristic is parent attending to child, good listening, child-directed Slower Speech Rate with Pauses • Clinician teaches parents/family to use a slower speech rate with appropriate pauses • Videos of Mr. Rogers on YouTube can be helpful models for clinician and parents • Emmy Acceptance Speech 1997 (E) • 143 • Parents/family benefit from practice with clinician to achieve a relaxed and smooth slower speech style • Then they can try it with child in clinic and at home; if child asks why parent is speaking slowly, parent can tell child that they talk too fast and need to learn to slow down Measurements • Severity Ratings – Use Lidcombe Severity Rating Scale which has 1-10 scale – 1=typical fluency; 10=extremely severe stuttering – Parents use this scale to report daily severity of child’s stuttering – Clinician may use this also in clinic session • Baseline Measures – Clinician records first 10-15 minutes of each clinic session and notes child’s SR for session and compares with parent’s SR 35 4/3/2016 Severity Rating Scale for Parents of Preschoolers • Used in Lidcombe Program (Onslow, Costa & Rue, 1990) • Parents mark an “x” in relevant box at end of each day to indicate severity of stuttering for day • Weekly charts are used by parents and clinical to assess child’s progress • Evidence for its reliability and validity * * * * * * * Supporting Data • Evidence that when mothers slow speech rate, child becomes more fluent (Stephanson-Opsal & Bernstein Ratner, 1988) • Evidence that when parents change interactions, child becomes fluent (Gottwald, 2010; Guitar et al., 1992) Older Preschool Children: Beginning Stuttering • Child is between 3.5 and 6 years old and has been stuttering for at least nine months • Stuttering consists of repetitions, often with tension, as well as tense prolongations, and some blocks • Escape behaviors; may be some avoidances • Feelings of frustration and embarrassment 36 4/3/2016 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) (Millard, Nicholas & Cook, 2008) • Rooted in “multifactorial” model of stuttering • Collaborative, flexible approach tailored to individual family • Stuttering may be openly discussed and acknowledged with child • Although this is primarily an indirect approach • Tools based on • child assessment, • parent interview, and • guided observation of videotaped parent-child play to determine physiological, linguistic, environmental or psychological factors Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) • Basic goals • Increase parent’s abilities to manage stuttering • Reduce family anxiety about stuttering • Decrease children’s stuttering to below 3% Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) • Intermediate Goals • To have parents identify and then change interaction patterns so that they become fluency facilitative • Increase parent’s confidence and decrease their level of concern re stuttering (questionnaire responses, homework sheets, verbal responses) • Gradually decrease child’s stuttering (stuttering frequency measures, parents severity ratings) 37 4/3/2016 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) • Major activities • • • • Individual therapy sessions Video recording and playback of parent-child interactions Discussions between parents and clinician (E) Homework for parents • Special Time (5 minutes of play time 3-5 times a week for each parent) • Reflect on how special time is going, whether goals are achieved Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) Session 1 - Clinician feedback from evaluation and ‘discovery’ while watching videotape. - Management and Interaction tools are chosen. - “Special Time” is negotiated. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) Interaction Tools During Play: • Follow child’s lead during play and verbal interaction (less physically active role); • Reduce instructions and questions (use comments instead); • Maintain attention with eye contact, showing interest, encouragement and praise • Reduce speech rate; • Increase duration of turn-taking pauses; • Reduce language demands (i.e. vocabulary, grammar, length/complexity of utterances, amount of talking, “performance” requests) 38 4/3/2016 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) Session 2 Videotape parent-child play and observe use of selected interaction tools and their effectiveness; Parent taught to observe relationship between child “stressors” (internal and external) and fluency, and modifies/manipulates when possible Provide feedback sheets and schedule weekly parent visits Time commitment • 1 hour per week for 6 weeks • Then weekly 10-minute telephone contacts for 6 weeks • Then 1 hour consolidation session • Checkup every 3 months for 1 year • Total contact time 8 hours • Total duration of treatment 12 weeks + 1 year of monitoring PCI Outcome Data • Case studies • Matthews, Williams, & Pring, 1997 • Crichton-Smith, 2002 • Millard, Nicholas, and Cook, 2008 (%SD reduction from 8.4% to 2.7% after a year of treatment) 39 4/3/2016 Lidcombe Program Onslow, Packman & Harrison, 2003 • Overview • • • • • • • http://sydney.edu.au/health-sciences/asrc/ http://sydney.edu.au/health-sciences/asrc/downloads/index.shtml Parent delivered in-home operant program praise about every fifth utterance Gentle correction for unambiguous stutters, only once per five praises Parent guided by weekly clinic visits Initially in structured sessions, then in unstructured sessions Data guides changes in program • Parent collects daily Severity Ratings (SRs) • Clinician collects %SS (or SRs) at clinic visits Lidcombe Program • Basic goals • Direct treatment for stuttering • Behavior therapy for children younger than 6 years • Decrease children’s stuttering to below 1% • Major activities • Individual therapy sessions • Clinician trains parents to administer praise and corrections in structured and unstructured daily situations Clinical Procedures • Stage 1: First Clinic Visit • Clinician assesses child’s %SS or SR in 300 syllables of the child’s conversational speech (standard for every clinic visit) • Clinician teaches parents about using SRs on a 1-to-10 scale to rate child’s fluency every day (E) • To calibrate parent, clinician may ask parent to rate child’s speech in previous 300 syllable sample; parent’s and clinician’s ratings then compared and discussed 40 4/3/2016 Clinical Procedures • Clinician teaches parent to conduct daily treatment conversation at home for 10-15 minutes each morning • • • • Conversation must be fun for child Keep child’s response fluent by adjusting its length and complexity Praise after every fifth fluent utterance: e.g., “That was really smooth!” Praise must be specific to speech (“smooth talking!”) rather than general (“good!”) Subsequent Clinic Visits • Three goals • Assess child’s speech • Discuss SRs and other indicators of progress • Introduce new procedures when appropriate • After child’s speech is assessed, she plays by herself as parent and clinician openly discuss child’s progress Subsequent Clinic Visits • Once parent is comfortable with using praise, gentle corrections are introduced: • After five praises for fluency, the next stuttered word is commented on, acknowledging stutter: “That one was a little bumpy,” using a non-negative inflection in the voice • After parent is comfortable with using acknowledgments for a week, requests for self-correction are taught • “‘Truck’ was a little bumpy. Can you try that again?” • If child says the word fluently, parent then praises: “Nice job of making that word smooth!” • Style of both praise and corrections can be adjusted to suit the child’s and family’s preferences 41 4/3/2016 Stage 1: Introducing Unstructured Treatment Conversations • When structured conversations have been going well and the child’s SRs and %SS show a reduction, unstructured conversations are introduced • This entails the use of praise, acknowledgment of stutters, and request for correction in everyday situations such as when child and parent are in the car or doing various activities around the house • Unstructured treatment conversations can start with only praise and contingencies for stutters introduced when appropriate Stage 2: Maintenance • Family begins Stage 2 when child meets criteria for three weeks in a row • %SS in clinic is below 1%SS • Week’s SRs are all 1 or 2, with at least four days being 1 • Stage 2 consists of 30-minute clinic visits scheduled at systematically increasing intervals as long as criteria are met: • Two visits at two-week intervals • Two visits at four-week intervals • Two visits at eight-week intervals • One visit at a 16-week interval Stage 2: Maintenance • If criteria are not met, parent and clinician jointly decide among several possible options: • Clinic visits increased in frequency to previous level • Weekly clinic visits • Reinstating either structured or unstructured clinic visits or both • Sometimes contingencies need to be adjusted • Ex. When child rarely stutters, praise for fluency is sometimes forgotten and parent only using requests for correction; praise needs to be used whenever corrections are used 42 4/3/2016 Time commitment • 1 hour per week for 6 weeks • 15 minutes of daily treatment by parents at home during stage 1 • Intermittent daily treatment by parents at home during stage 2 • Median of 11 weekly sessions to achieve fluency • 1 year of gradually faded contact Outcome Data • 42 children treated with Lidcombe showed near-zero levels of stuttering four to seven years after treatment (Lincoln & Onslow, 1997) • 12-week randomized control trail of Lidcombe (n=10) versus no treatment (n=13) showed that the treated children had significantly less stuttering than untreated (Jones et al., 2000) • Randomized control trial of Lidcombe (n=29) versus control (n=25) showed significantly greater improvement in Lidcombe treatment (Jones et al., 2006) What are the similarities between PCI and Lidcombe? Onslow, M., & Millard, S. (2012). Palin Parent Child Interaction and the Lidcombe Program: Clarifying some issues. Journal of fluency disorders, 37(1), 1-8. 43 4/3/2016 Direct Approach for Preschoolers • Goals • • • • Decrease time pressure and physical tension Reduce speech rate (level I) Contrast easy versus hard or smooth versus sticky speech (level II) Prevent/modify stuttering by using stretchy (=prolonged) speech and/or soft touches (=light articulatory contacts) (level III) Reduce speech rate (level I) • Turtle Speech • • • • Contrast the concepts of fast and slow One is more likely to lose control when doing something too quickly Fast = out of control Slow = in control Contrast Smooth vs. Sticky speech (level II) • Acknowledge that speech can be easy and smooth and can be hard, sticky, or bumpy • If child is not able to describe hard vs. easy speech, clinician can demonstrate different kinds of speech herself 44 4/3/2016 Stretchy Speech (level III) • Children may increase tension in their articulators or throat when initiating speech sounds • Teach them how to produce light articulatory contacts • Soft touches • Contrast hard vs. soft objects (marshmallows) • Level of practice increases from sounds through sentences Preschool-age children: Resources • 7 Tips for Talking with the Child who Stutters • http://www.stutteringhelp.org/videos • Special Education Law & Children Who Stutter • http://www.stutteringhelp.org/special-education-law-children-who-stutter • Stuttering Home Page • http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/kuster/schools/SID4page2.html 45