CLINICAL JUDGMENT FAITH BIAS: THE IMPACT OF FAITH AND A DISSERTATION

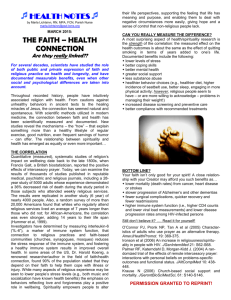

advertisement