United States Air Force Air Logistics Centers:

Lean Enterprise Transformation and Associated Capabilities

by

Jessica Lauren Cohen

B.A., Geology (1999)

Rice University

Sc.M., Planetary Geosciences (2001)

Brown University

Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Technology and Policy

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

September 2005

C 2005 Massachusetts Institute of TedI

All rights reserved / /

Signature of Author.

...............................................

gy

.........................

........ ..

Technology and Policy Program, Engineering Systems Division

st 12, 2005

............... ......

Dr. George Roth

Principal Research Associate, Lean Aerospace Initiative

Sloan School of Management

. bThesis Supervisor

.. ....

.. ............ ... - ..

C ertified by .............................................................

Certified by .................................... ......

..........

Prof.

D

•

orah

....i 1tinale

Co-Director, Lean Aerospace Initiative

Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems

-'

/I

Thesis Reader

Accepted by ........................

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

I

C----

.......................... ..........

_.... /

.....

.......

lof. Dava J.Newman

Director, Teo nology and Policy Program

Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems

JUL 3 1 2007

LIB ARF IES

~'CCHN~E

S

This page intentionally left blank.

United States Air Force Air Logistics Centers:

Lean Enterprise Transformation and Associated Capabilities

by

Jessica Lauren Cohen

Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division on 12 August 2005

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Technology and Policy

Abstract

Lean enterprise transformation entails a complementary set of initiatives and efforts

executed over a substantial period of time, in a consistent and coordinated manner, at all

levels of the enterprise. It builds upon ordinary organizational change in that a broader

set of people and functions will be affected, and non-traditional approaches and mental

models will continue to be exercised. I have developed and proposed a set of capabilities

that must be possessed by any enterprise in order for that enterprise to successfully

transform and sustain a new way of doing business. These capabilities have been drawn

and compiled from a combination of organizational change literature and models, as well

as personal experience and observations.

Between 2003 and the present, three US Air Force Air Logistics Centers (ALCs) initiated

lean enterprise transformation efforts. This notion was beyond the activities these sites

pursued in the past, as the ALCs were challenged to see their enterprises as a system that

needed to be optimized. I have used the capabilities developed to assess each ALC and

make suggestions regarding their future needs in executing lean enterprise changes. In

particular, I have focused on two of the twelve capabilities (a leadership team with a

shared mental model and a balanced and cascading system of metrics), and compared

each ALC to an ideal state and utilization of these capabilities. Further, I have examined

the Warner Robins ALC with respect to all twelve capabilities, in light of past work

conducted at the site.

The results of this research are two-fold. First, I have learned that there are certain

conditions that must be met before lean enterprise transformation can be attempted and

sustained. The readiness necessary can be assessed within a combination of the

qualitative results derived from a comparison with the ideal capabilities I have defined,

along with the quantitative results reported with the LAI Lean Enterprise Self Assessment

Tool. Second, I have determined that there are special practices and cultural aspects of

government enterprises that makes lean enterprise transformation particularly difficult for

them. This is the result of policies in place, and a tradition of strategic direction being

handed down from above.

Thesis Supervisor: Dr. George Roth

Thesis Reader: Prof. Deborah Nightingale

Principal Research Associate

Professor of the Practice

This page intentionally left blank.

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to a number of people for their assistance, guidance, and support as

I completed my thesis. The Lean Aerospace Initiative has been my home away from

home for two years, and this work would not have been possible without my colleagues

and advisors. Dr. George Roth and Prof. Deborah Nightingale offered guidance when I

needed it, assistance when necessary, and pushed me to finish when I needed that more.

The LAI support staff and students also helped me keep everything (work related and

not) together.

Sydney Miller of the Technology and Policy Program also proved to be an invaluable

resource for me, in good times and bad. She assured me I would finish, no matter how

long it took me to get there, and worked the system on my behalf. My friends and fellow

students at TPP, and their emotional and social support, are also much appreciated.

And for my husband, Patrick, there are no words to convey the sense of gratitude and

devotion I feel. Without him, there is no way I could have completed this work. Thank

you, my love, for allowing me to drive you crazy for the past six months.

This page intentionally left blank.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I

INTRODUCTION ......................................

2

LITERATURE REVIEW AND METHODOLOGY ........................

3

LEAN ENTERPRISE CHANGE CAPABILITIES ...................

4

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AIR LOGISTICS CENTERS: A PRIMER .. 82

5

AN IN DEPTH EXPLORATION OF TWO LEAN ENTERPRISE

CHANGE CAPABILITIES ..................................... .....

10

.

22

44

............. 92

6

AN IN-DEPTH DISCUSSION OF WARNER ROBINS ALC ................... 122

7

POLICY BARRIERS TO CHANGE AND CONCLUSIONS .................... 168

This page intentionally left blank.

1 INTRODUCTION

10

1.1

What is lean?

10

1.2

What is a lean enterprise?

12

1.3

What is lean enterprise transformation?

13

1.4

What is a lean enterprise transformation capability?

14

1.5

Can lean enterprise transformation be successful in a government context?

16

1.6

Unique Opportunities for this Research

18

1.7

Larger Theory of Enterprise Change

19

1

Introduction

1.1

What is lean?

Lean, as a concept, has two driving forces: to continuously eliminate waste, and to

continuously add value (Womack & Jones, 1996). Practitioners of lean should be

constantly asking themselves, "Am I doing the right job at the right time?" But lean is

more than a set of tools and techniques. Advocates of this way of thinking suggest that

lean must become an ingrained mindset that allows people to see their world differently,

as they continually strive to improve all aspects of production and value delivery to all

stakeholders using data collected locally. Any group of workers looking to employ lean

techniques must become a "community of scientists" constantly applying the scientific

method, over and over again, to recognize areas of concern, identify and test possible

solutions, and then implement new standard operating procedures (Spear & Bowen,

1999).

In its most common form, lean is a synonym for the Toyota Production System and has

roots in traditional manufacturing arenas. In "The Machine That Changed the World",

Womack, Jones, and Roos outline the differences between Toyota and other automobile

manufacturers, and highlight the techniques and practices that allow Toyota to be so

much more effective and efficient at their stated tasks. These techniques include just-in-

time inventory and production, kaizen or methods of continuous improvement, and the

community of scientists described above, among others (Womack et al., 1991).

In the 1996 publication "Lean Thinking", Womack and Jones propose a series of five

steps that will allow any manufacturer to become lean, at least in the most general sense.

These steps include:

Step 1 - Specify customer value by product;

Step 2 - Identify the value stream for each product;

Step 3 - Make the value flow without interruption;

Step 4 - Let the customer pull the value from the producer; and

Step 5 - Pursue perfection.

The first four steps are designed to progress sequentially in order to transition to a lean

manufacturer. The final step is intended as a reminder that the process of transitioning to

lean should never end, and that the steps can be repeated to gain further improvements,

with perfection as the ultimate (albeit unattainable) goal (Womack & Jones, 1996).

In its current form, however, lean has not been restricted to only manufacturing

environments. Lean was originally a term used to illustrate the series of practices at

Toyota, the best example, among others, of Japanese production methods. In the US, lean

application began in the manufacturing areas, but corporations quickly realized that it

could be applied throughout the enterprise. Many examples exist throughout the

aerospace community of lean deployment in non-manufacturing areas. These areas

include personnel and hiring, purchasing and supply chain management, financial

management, leadership processes, and other parts of large organizations. Furthermore,

once lean thinking is applied beyond the boundaries of one organization, be that

functional or physical, you are approaching the realm of the lean enterprise.

1.2 What is a lean enterprise?

A lean enterprise is an integratedentity that efficiently creates valuefor

its multiple stakeholders by employing lean principles andpractices.

(Murman et al., 2002)

By definition, an enterprise is larger than an individual organization. An enterprise will

be comprised of multiple organizations with a myriad of functional responsibilities.

Efficient management of the enterprise will require identification of cross-boundary

dependencies and interactions. Furthermore, leaders must actively pursue a systems

perspective of the enterprise in order to avoid sub-optimization at the organizational or

functional level. In order to accomplish this, mental models of leadership must be shifted

away from functional organization or silo-ed requirements. Everyone must work

together, understand their place in the enterprise, and embrace a lean culture.

The types of stakeholders involved in enterprise activity will overlap with those

concerned with individual organization progress, but it is possible that there will be a

greater number of stakeholders to satisfy in the enterprise environment. Enterprise

stakeholders will include all employees (including any union affiliations if they are

present), customers, suppliers, leadership and management, and the local community, as

well as others. Just as a customer pulls value from a lean producer, the ideal lean

enterprise will allow all stakeholders to pull value. In the enterprise situation, the needs

of each stakeholder must be balanced against the needs of other stakeholders and the

enterprise itself. In this manner, all concerns can be addressed and encompassed early in

the value delivery process.

The lean enterprise, as I have defined it will adapt lean principles and practices to be used

throughout its operations, and not just limit them to the manufacturing arena. Truly

successful lean enterprises will use lean thinking as they manage operation and support

functions and financial budgeting questions, as well as the overall strategic direction for

the future. A lean enterprise will use lean techniques and tools at the local level and the

enterprise level, and at every level in between. I believe that the challenge of going from

lean at a local level to lean at the enterprise level, and developing and cultivating a truly

lean culture, is embodied in the concept of lean enterprise transformation.

1.3

What is lean enterprise transformation?

Lean enterprise transformation is the journey that employs lean concepts, tools, and

techniques towards the end goal of a lean enterprise. This journey will bring the whole

enterprise, and all personnel, onto the same page when it comes to the core mission and

vision of the enterprise goal. Lean enterprise transformation should be designed to

eliminate the undue and burdensome influence of organizational and functional silos, if it

exists, with a focus on greater communication and less isolation. The wave of

transformational efforts should eventually extend to all suppliers and customers, but

initially and at the very least, should seek out and incorporate their requests and

recommendations.

Lean enterprise transformation entails a set of complimentary initiatives and efforts

executed over a substantial period of time. This must be done in a consistent and

coordinated manner at all levels of the enterprise. Lean enterprise transformation builds

upon more traditional organizational change and lean improvements in that a broader set

of people and functions will be affected. Also, I think non-traditional approaches and

mental models will likely be exercised.

1.4 What is a lean enterprise transformation capability?

A lean enterprise transformation capability is the capability to execute or support a

certain task that is necessary, but not sufficient, for lean enterprise transformation. This

is a capability that must be possessed by any large complex enterprise and deployed in

order for that enterprise to initiate a successful transformation process, and then sustain a

new way of doing business. Once the capability is developed, the whole enterprise

should have access to it and utilize it fully.

In order to accomplish the lofty goals that proponents of lean advocate, I have proposed a

set of twelve lean enterprise change capabilities that I believe are necessary for initiation

and sustainment of lean enterprise transformation. The capabilities have been drawn and

compiled from a combination of organizational change literature and models, and

personal experience and observations. The set of capabilities include:

1. A leadership team with a shared mental model;

2. Planning and implementation process;

3. Balanced and cascading system of metrics;

4. Standardized processes and a team to track them;

5. Compensation and reward system;

6. Developing and deploying vision and mission;

7. Communication and public relations abilities;

8. Change management;

9. Cadre of change agents;

10. Context for local experimentation;

11. Continued learning and self-renewal; and

12. Training and education.

No one of these capabilities, which are explained in Section 4, is more important than the

others. They should be viewed as a set of capabilities, rather than individual abilities that

can be cultivated independently. The systematic nature of this set should reflect the

systems approach that will enhance any lean enterprise transformation.

1.5 Can lean enterprise transformation be successfulin a government

context?

In the vast majority of US Government affiliated enterprises, there is no profit motive or

measure associated with value production. The customers and oversight bodies are

complex and made up of multiple entities with particularly points of view and priorities

as to what is valued. This fact enhances the likelihood of greater resistance to lean

enterprise transformation from some workers, as the bottom line reasons for

improvements will be harder to decipher and quantify. Even though this is not

intentional, it is possible that these policies have the affect of dampening the influence of

the lean enterprise change capabilities outlined above.

Within the Air Force enterprises that I have observed, it is hard for leaders and employees

to agree on goals with clarity, and thus they cannot agree on what is waste and what is

value. They often do not take time to figure this out before undertaking initiatives,

because it is not in their culture to do so. They want to act immediately, often before

taking the time to collect and analyze data. Historically, successful leaders have

embraced this "act immediately" mentality, and have been rewarded for this behavior. I

believe these policies and cultural attributes will likely hamper lean enterprise

transformation if left unchecked.

In a broader sense, government enterprises have long relied on someone else for strategic

direction. This usually comes from high in the military chain of command, including

Congress, the Pentagon, and ultimately, Department of Defense directives and mandates.

This results in a culture in which Air Force enterprises are expected to implement and

refine someone else's strategic plan, and not necessarily devise their own. Now, this is

changing. Throughout the military complex, smaller enterprises are being asked to

complete their own strategic planning process, and undergo transformations designed to

enhance autonomy, while still maintaining structural ties and resources dependencies.

These ideas are an essential part of lean concepts and lean enterprise thinking. These

enterprises are left with a competency gap: they must learn how to plan and implement

their own strategic directives, while still maintaining alignment and consistency with the

wider environment.

I have observed this situation at the three US Air Force Air Logistics Centers (ALCs)

studied for this work:

* Ogden ALC at Hill Air Force Base in Utah (OO-ALC);

* Oklahoma City ALC at Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma (OC-ALC); and

* Warner Robins ALC at Robins Air Force Base in Georgia (WR-ALC).

The ALCs are independent enterprises, but they are also part of the larger US Air Force

complex. Their extended enterprise includes each other, and extends upwards through

the Air Force chain of command, through the Pentagon and the Department of Defense,

and all the way to Congress and the President of the United States. For the purposes of

this thesis, I will define three separate systems, even though these ALCs are actually subsystems in the larger Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) enterprise. This definition

will help me focus on steps that can be taken by each ALC to further their goal of lean

enterprise transformation.

This thesis will address the lean enterprise transformation attempts of the three ALCs in

light of this restrictive government environment. To assume they are capable of

everything a commercial enterprise is capable of is a mistake, in terms of lean enterprise

change capabilities, understanding of their customer, and business motivations for change

(such as savings reinvestment or recognition of lean activity in performance reviews).

This does not mean that lean enterprise transformation will be impossible, but it does

mean that it will be more difficult, and may take longer. I believe the leadership teams at

all three ALCs are capable of rising to this challenge.

1.6 Unique Opportunitiesfor this Research

Research access to each ALC was provided due to on going involvement between the

ALC leadership teams and the Lean Aerospace Initiative (LAI), my research group at

MIT. I was originally introduced to life and work at the ALCs through my work with

four case studies completed at WR-ALC in January 2004. These case studies examined

the lean history of WR-ALC, and the lean efforts within the C-130, C-5, and Purchase

Request areas. In 2004 and 2005, LAI engaged with each ALC in order to facilitate an

enterprise assessment process called Enterprise Value Stream Mapping and Analysis

(EVSMA). An alpha-test of EVSMA was conducted at OO-ALC, followed by a betatest of EVSMA at OC-ALC, a gamma-test of a modified EVSMA process at WR-ALC.

This research is an inductive study. I was brought into each engagement in order to

observe activities and document progress. Through these observations, and my reading

of academic change literature, I devised and developed the set of twelve lean enterprise

change capabilities.

1.7 Larger Theory of Enterprise Change

This research is part of a larger attempt at LAI to identify a broad theory of enterprise

change. My piece examines enterprise transformation in the context of the three ALCs.

This work will be combined with research done at other sites, both military and

commercial. The theory developed will later be tested at a variety of enterprises and

institutions. However, recommendations and suggestions can be made to the sites in

question based on the preliminary analysis provided and a comparison with

organizational behavior literature.

This page intentionally left blank.

2

LITERATURE REVIEW AND METHODOLOGY

2.1

From Commercial Organizational Change to Governmental Lean Enterprise

Transformation: An Overview

22

22

2.2.1

2.2.2

2.2.3

2.2.4

General Models of Change

Theorizing Change

Breaking the Code of Change

Leading Change

The Dance of Change

23

24

25

26

27

2.3.1

2.3.2

2.3.3

2.3.4

2.3.5

2.3.6

2.3.7

Barriers to Change

Identifying Resistance

Structural Inertia

Roles of Outside Influences

Organizational Identity and Image

General Cynicism

Perception of Fads and Fashions

The Role of Managers: Showing Emotional Commitment

28

29

30

32

32

33

34

35

2.4

Policy Literature Discussion

36

2.5

Methodology

40

2.2

2.3

2

Literature Review and Methodology

2.1 From Commercial Organizational Change to Governmental Lean

Enterprise Transformation:An Overview

Organizational change has been studied for quite some time now (Beer & Nohria, 2000).

In the past 60 years, scholars have often chosen to focus at the organizational level, while

including details about change effects on individuals and teams. Many aspects of change

efforts and programs, models and attempts, have been studied in both qualitative and

quantitative manners (Kotter, 1996).

I believe expansion from the organizational level to the enterprise level is a logical jump,

and is a reasonable progression of scholarly work in this field. However, this leap of

faith does present some complications. As you cross organizational and functional

boundaries, responsibilities and expectations are more likely to change (Murman et al.,

2002). Also, repercussions can become more numerous and potentially more

complicated. Both of my assertions would lead to an environment less conducive to

change or transformation.

There is a difference between change and transformation. Some leadership team

members that I spoke with indicated that transformation, for them, implies a radical, and

perhaps revolutionary, leap away from business, and thought, as usual. Transformation is

the sum of multiple change efforts conducted in a coordinated manner over a significant

period of time. The net result of this coordinated move is a dramatic change in state, or a

"transformation." I believe enterprise transformation can be thought of and accomplished

as the aggregate of smaller organizational change projects and initiatives.

We are entering new and uncharted academic waters with this expansion from

organizational change to enterprise transformation. The current literature available deals

primarily with organizational change. In the following discussions, I will make all

attempts to justify the expansion, and address any discrepancies where needed.

Furthermore, my reading of the current literature has led me to the conclusion that it deals

primarily with commercial organizations. Few studies have been conducted examining

change in government settings. This thesis is concerned principally with governmental

entities and Air Force Bases in particular. Again, parallels will be observable, and

differences will be noted as appropriate.

2.2 General Models of Change

In order to better assess the change processes currently in progress at the ALCs, we must

first be comfortable with an ideal change process. I have selected four change models

which, when viewed as a set, quite adequately describe a strategy of change management.

They complement each other, and fill gaps were necessary. They present a balance of

bottom-up and top-down change methods. If used sequentially, along with feedback and

re-work when necessary, I believe a leadership team would be well served by these

models. This opinion is based on my observations of leadership teams and my notion of

what I believe is missing in their current efforts.

2.2.1 Theorizing Change

Theorization is one piece of a broader model of institutional change. This step, described

by Greenwood, Suddaby, and Hinings, supports the notion that before an organization

can undergo change, they must conceptualize the change they are seeking, and truly

understand the implications of the initiative they are attempting to begin. Theorization

involves two specific tasks: 1) specification of a "general organizational" failing for

which a local innovation is a "solution or treatment;" and 2)justification of the

innovation (Greenwood, Suddaby, & Hinings, 2002).

Figure 2.1 Model of Institutional Change (Greenwood).

Theorization of change is important because it connects to one of the central concerns of

institutional thinking: the conferring of legitimacy. By conferring legitimacy, people at

all levels of the organization can buy into the change process, and more readily accept the

new procedures being foisted upon them. Theorization is integral to institutional change,

and it allows the rendering of ideas into understandable and compelling formats

(Greenwood et al., 2002).

2.2.2 Breaking the Code of Change

Once change has been theorized, senior leaders must decide on the change management

techniques they are going to use to justify, initiate, and sustain that course of action. In

"Breaking the Code of Change," Beer and Nohria (editors) present the findings of a

Harvard Business School conference at which possible methods were debated.

Underlying much of the debate is the difference between Theory E and Theory O (Beer

& Nohria, 2000).

Theory E and Theory O are two strategies available for change management

professionals and leaders. Both strategies have benefits and costs, and both are valuable

in different situations. Beer and Nohria define the theories as follows:

Theory E has as its purpose the creation of economic value, often

expressed as shareholdervalue. Itsfocus is onformal structure and

systems. It is driven from the top with extensive helpfrom consultants

andfinancial incentives. Change is planned andprogrammatic.

Theory 0 has as its purpose the development of the organization's human

capabilityto implement strategy and learnfrom actions taken about the

effectiveness of changes made. Itsfocus is on the development of a highcommitment culture. Its means consist of high involvement, and

consultants and incentives are relied onfar less to drive change. Change

is emergent, less planned andprogrammatic. (Beer & Nohria, 2000, p.3)

Change management is essential to any type of planned change effort. The truly

important conclusion to be drawn from this work is that every organization can, and

should, customize the best balance for their predicament. This balance is known as

Theory OE. Every situation calls for a different equilibrium. The challenge for leaders is

to recognize the differences between the two strategies, assess their strengths and

weaknesses, and achieve the correct alignment.

Theory E

Theory O

Theory OE

Goals

Maximize Value

Develop capabilities

Leadership

Top down

Bottom up

Embrace paradox

between value and

organizational capability

Set direction from top

and engage people from

Dimensions

of Change

below

Focus

Structure and systems

Corporate culture

Focus simultaneously on

hard and soft

Process

Reward

System

Use of

Consultants

Programmatic

Financial incentives

lead

Expert consultants

analyze problems and

Emergent

Commitment leads

and incentives lag

Consultants support

process to shape

Plan for spontaneity

Incentives reinforce but

do not drive change

Consultants are expert

resources who empower

shape solutions

own solutions

employees

Table 2.1 Descriptions of Theory E, Theory 0, and Theory OE (Beer & Nohria, 2000).

2.2.3 Leading Change

Subsequent to selecting a change management strategy, leaders must initiate and sustain

the change planned. In his 1996 book "Leading Change," Kotter outlines an eight-stage

program designed to highlight errors to avoid and opportunities for success during all

periods. He acknowledges that change is hard and that most efforts will fail, but stresses

that organizations who follow his steps are more likely to be victorious. The eight-stages

are: 1) establishing a sense of urgency; 2) creating the guiding coalition; 3) developing a

vision and strategy; 4) communicating the change vision; 5) empowering employees for

broad-based action; 6) generating short term wins; 7) consolidating gains and producing

more change; and 8) anchoring new approaches in the culture (Kotter, 1996).

One lesson from this work is that change involves numerous phases that, taken together,

usually take a long time. And sometimes, that amount of time is longer than some CEOs

are willing to wait. However, he cautions that skipping steps creates only an illusion of

speed and never produces a satisfying result (Kotter, 1995). A second important lesson is

that critical mistakes in any of the phases can have a devastating impact, slowing

momentum and negating previous gains (Kotter, 1996). The model proposed by Kotter is

an example of a Theory E driven change process.

2.2.4 The Dance of Change

As any change initiative progresses, stakeholders will display resistance; this is just a fact

of life and an especially salient fact of change. Instead of addressing change initiatives

and management techniques directly, "The Dance of Change," by Senge, Kleiner,

Roberts, Ross, Roth, and Smith, book attempts to direct change through mitigation of

barriers, such as those discussed later, as well as others. In particular, they advocate the

creation of a learning organization, and a culture that can mitigate resistance effectively

on its own.

All organizationsthat innovate or learn come up againstinnate challenges

that blockprogress. The harderyou push against these challenges, the

more they seem to resist.But ifyou can anticipate them, and buildyour

capabilitiesfor dealingwith them, they become opportunitiesfor growth.

(Senge et al., 1999)

This can be a very effective method of change and transformation effort enhancement if

followed well, and an example of a Theory O driven change process. However, in order

for this strategy to be successful, senior leaders and change agents must be able to

identify barriers to change. Those most commonly associated with large-scale enterprise

transformation are discussed below.

2.3 Barriers to Change

As discussed earlier and in the "Dance of Change", resistance is something to be

expected, understood, dealt with, and conquered, as opposed to feared and forgotten until

it is too late. The capability to develop these answers, and train people to have them on

hand, is a necessary condition for successful change. The first step is to identify the

different barriers to change, and then address each one (or at least the primary drivers)

before they overwhelm the change effort. The following sections address some of the

most commonly observed types of barriers to change:

* Identifying Resistance

* Structural Inertia

* Roles of Outside Influences

* Organizational Identity and Image

* General Cynicism

* Perception of Fads and Fashions

* The Role of Managers: Showing Emotional Commitment

I have chosen these because I believe they best describe the types of resistance I

witnessed at the three Air Logistics Centers.

2.3.1 Identifying Resistance

Resistance to change will likely be an obstacle to successful implementation of

reinvention initiatives (Trader-Leigh, 2002). The different types of resistance

encountered will be based on how individuals and organizations perceive their goals are

affected by the change. In other words, if one man feels his job will be affected more

than someone else on the other side of the factory or office, change agents should expect

to see more resistance from him. Trader-Leigh suggests that all change agents should

anticipate resistance and learn to manage it effectively.

This study is particularly interesting because it is one of the few pieces of the literature to

deal with a governmental organization. She identified key forces or resistance at the

State Department during a time of transformation. These forces include self-interest,

psychological impact, and tyranny of custom, redistributive effects, destabilization

effects, culture compatibility, and political forces (Trader-Leigh, 2002). I have spoke

with people at the ALCs who indicated they had observed all of these destabilizing forces

during local lean efforts, and they believed these forces were working against the

transformation process.

2.3.2 Structural Inertia

...for wide classes of organizationsthere are very strong inertial

pressures on structure arisingfrom both internalarrangements(for

example, internal politics) andfrom the environment (forexample, public

legislation or organizationalactivity). To claim otherwise is to ignore the

most obvious feature of organizationallife. (Hannan& Freeman, 1977)

Structural inertia has been defined as the relationship between the speed at which an

organization can transform (and thereby succeed or die - as shown in Figure 1) and the

rate at which the surrounding environmental conditions change (Hannan & Freeman,

1984). If an organization can change rapidly in the face of new circumstances, it is said

to have low inertia. Conversely, if an organization has become so complex that it cannot

react in a flexible manner to new situations, it is said to have high inertia (Kelly &

Amburgey, 1991). Furthermore, because organizations exist in various environments, it

is possible to be considered flexible with low inertia in one context, while being seen as

steadfast with high inertia in another (Hannan & Freeman, 1984).

In their 1977 paper, Hannan and Freeman attempt to extend evolutionary theory into the

realm of organizations, and they feel justified in doing so. They use an analogy of

"inertial forces" as those forces or outside environmental pressures that would cause an

organization to undergo change, or an animal to evolve. They argue that high levels of

inertia (or un-changeability) result from external pressures.

However, they also contend that this is part of organization natural selection, and that, "If

selection favors reliable, accountable organizations, it also favors organizations with high

levels of inertia (Hannan & Freeman, 1984)." They suggest that inertia increases with

age, and therefore older organizations are less likely to change, but also more likely to

survive in the long run. They are unsure of how size plays a role, although they are

leaning towards concluding that smaller organizations can change more easily (Hannan &

Freeman, 1977).

All of the factors leading to high structural inertia, and therefore low changeability, are

resident and descriptive of all three Air Logistics Centers. They are older, large, complex

enterprises stuck in a multi-faceted and uncertain environment. My reading of this

concept leads me to believe that transformation at the ALCs will be extremely difficult,

unless they can develop the capability to plan within this environment, or modify their

situations sufficiently. Hannan and Freeman (1977) suggest that some organizations will

die out if they are unable to change, and that this process is part of the natural course of

organizational evolution.

2.3.3 Roles of Outside Influences

The central thesis of this concept is that outside influences, and especially marked

environmental punctuations, can dramatically reduce pressures and rewards for

organizational inertia. Thereby, outside influences, such as regulatory or policy shifts,

can alter both an organization's propensity for change and their survival chances

following change (Haveman, Russo, & Meyer, 2001).

Essentially, this concept provides a balance for structural inertia, and shows that at times

of outside pressure an organization can react quickly if they try hard enough. The ALCs

are currently concerned with two types of outside influence that could alter the course or

effectiveness of their lean enterprise transformation. First, the on-going war on terror has

driven them to higher rates of production and shorter time scheduled than were necessary

before. Second, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process can significantly

shift their business and transformation plans if any of these bases is put on the closure list

(see Section 5).

2.3.4 Organizational Identity and Image

In their 1991 paper, Dutton and Dukerich defined the terms organizational identity and

organization image, with a particular nod to the effects of these concepts on

organizational change. Organizational identity is the sum of the distinctive attributes of

one organization, as seen by someone on the inside. Organizational image is what an

insider believes is perceived by an outsider about the organization in question (Dutton &

Dukerich, 1991).

Both of these concepts can influence a senior leader as they are crafting the case of

change, and can either hamper or hasten transformation efforts. Gioia, Schultz, and

Corley discuss the potential benefits of a flexible and fluid organizational identity in their

2000 paper. They introduce the concept of adaptive instability of organizational identity

and image. They argue that this adaptive instability allows for flexibility and change in

the long run, and is a concept that should be further explored in research and in practice

(Gioia, Schultz, & Corley, 2000).

The ALCs have an organizational identity that is firm and unresponsive, but respected on

the outside, leading to a positive organizational image. This lack of flexibility, and the

structure of the Air Force as a whole, could thwart lean enterprise transformation efforts

if not handled and addressed appropriately.

2.3.5 General Cynicism

Cynicism can manifest itself in a myriad of fashions within an organization or enterprise.

Dean, Brandes, and Dharwadkar (1998) define organizational cynicism as, "a negative

attitude toward the organization, comprising certain types of belief, affect, and behavioral

tendencies." This quality or feeling can be resident in any person associated with the

organization, either inside or outside. And these feelings can disrupt the transformation

process, by increasing resistance and general bad feelings towards new processes or

leaders (Dean, Brandes, & Dharwadkar, 1998).

Unfortunately, the authors do not give suggestions for how to manage this occurrence,

but instead outline a future research agenda for further study.

2.3.6 Perception of Fads and Fashions

As organizations change, or choose not to change, over time, they make decisions just as

any rationale person would. Sometimes those decisions are efficient, and result in

innovation seen as beneficial. Other times, organizations chose innovations or

developments that are actually sub-optimal for their predicament. This duplicity is

known as the efficient-choice perspective, and in his 1991 paper, Abrahmson

acknowledges the limitations of this school of thought by describing situations in which

companies do not choose efficient innovations, or they choose inefficient technologies.

In order to extend this model, the Abrahamson describes three additional perspectives

that might allow us to better understand the diffusion of innovations throughout

organizations within a particular industry:

Fads - organizations look to imitate their successful friends because they are

unsure of their goals and are not under a lot of outside pressure;

* Fashions - these trends lead to the adoption of inefficient innovations because

groups are still unsure but this time they are susceptible to outside pressure; and

* Forced-selection - this leads to coercion from more powerful groups over less

powerful groups, and suggests that inefficient innovations will be adopted, or that

efficient ones will be passed.

He suggests that if these perspectives can be applied to decisions already made, there is

no reason for leaders not to take these assumptions and descriptions into consideration

when making new decisions, and avoid the pitfalls of peer pressure. Alternatively, he

also contends that even symbolic adoption of some innovations will help in long run

reputation, even if the specific technology is not important to the business bottom line

(like the wide-spread adoption of quality circles) (Abrahamson, 1991).

2.3.7 The Role of Managers: Showing Emotional Commitment

Managers can be sources of resistance, but, if trained properly, they can also be a positive

force for change and honesty in the transformation process. In his 2002 paper, Huy

discusses the benefits of managers showing emotional commitment to change. He

suggests that managers should be trained in how to show personal emotional commitment

to the change in question, as well as how to balance the emotional needs of employees

and answer their questions and concerns (Huy, 2002). This could be a new role for

middle managers during radical change processes. If this managerial emotional

commitment could be facilitated, fostered, and grown, less resistance may be

encountered.

A conceptual model for how managers should go about showing this emotional

commitment was presented by (Isabella, 1990). In the course of her research, she is able

to use the evolving interpretations of key events in a radical change process by managers

to fully understand the history of a particular organization (Isabella, 1990). Also, she

suggests a four stage cognitive model that describes what managers are trying to do

during each stage of a change process. These stages include: 1) anticipation, 2)

confirmation, 3) culmination, and 4) aftermath (Isabella, 1990). She also highlights the

event triggers that help managers know when to move from one stage to the next. She

recommends keeping everything in terms of the personal - "what is this going to do to

me."

Senior leadership at all three ALCs will need to convince their middle managers to

express this emotional commitment if their lean enterprise transformation efforts are

going to succeed. Middle managers are the link between top-down and bottom-up

change processes, and the two must be used in conjunction to assure triumph.

2.4 Policy Literature Discussion

Within any enterprise, policies are used to construct the environment in which all

business, and change, occurs. This is especially true of any governmental organization,

including the US Air Force, and therefore, the three Air Logistics Centers. At OO-ALC,

OC-ALC, and WR-ALC, policies are set locally, as well as outside of the enterprise

boundaries by others within the military chain of command. Recent analyses of these

policies and contexts have revealed some intriguing facets of these enterprises.

In 1999, the General Accounting Office (GAO) issued a report that examined three

reform initiatives underway at the (five) Air Logistics Centers at the time. One of those

initiatives was Agile Logistics, which was an attempt to bring lean principles to the world

of Air Force logistics. This report identified a number of management changes that

would better support initiative implementation. Included in this list were:

* Developing an implementationplan that establishesstandardmeasuresfor

assessing whetherprocess improvement initiativesare achieving desiredgoals

and results;

* Assessingprogress toward implementing standardorganizationalstructures and

processes;

* Addressing weaknesses in information management systems used to manage

process and assess activityperformance, consistent with the Clinger/CohenAct

and Year 2000 requirements;

* Identifying costs offully implementing the initiatives and avoidingpremature

budget reductions in anticipationof savings; and

* Developing effective working agreements with other defense logistics activities

that are key to timely access to needed repairparts and successful implementation

of logistics reforms (GAO, 1999).

Of these changes proposed, all deal with policies internal to the enterprises. Of particular

interest is the recommendation regarding information management and the

Clinger/Cohen Act of 2000. This act deals with information technology and

management, and stipulates how new IT systems should be introduced and utilized. This

is an example of a policy set outside of the ALCs that greatly affects their transformation

abilities. Interviewees at each ALC indicated that this act has prevented them for

purchasing or implementing information technology solutions that they would have

preferred to see introduced.

The last two recommendations are also quite interesting. The "identifying costs"

proposal hints at the fact that while acting upon these reform initiatives, the ALCs

attempted to quantify and reinvest savings that never materialized (GAO, 1999). Policies

must be put into place to ensure this does not happen again. The last proposition

acknowledges the fact that the ALCs must work more closely with each other and their

customers in order to best reform their supply chain management skills. Policies that

encourage teaming and partnering can work towards achievement of this goal (GAO,

1999).

In addition to other governmental organizations, the ALCs have also been assessed by

outside groups and think tanks. In 2004, the RAND Corporation issued a report (part of

an on-going Air Force funded series of studies) that examined organizational levers that

could be used to enhance acquisition reform implementation. In particular, they looked

at WR-ALC, and attempted to identify the levers available to leaders to further adoption

of new acquisition processes. Through interviews and surveys, they found that the

following levers had either positive, negative, or no affects on process adoption:

* Trainingin acquisitionreform -positive;

* Attitude towardacquisitionreform -positive;

* Effective teaming - negative;

* Contractorpartnering-positive;

*

*

*

*

*

Leadershipconsistency -positive;

Performanceincentives - none;

Air Forcepartnering- none;

Performanceevaluation - negative; and

Job experience - negative (Chenoweth, Hunter,Keltner, & Adamson, 2004).

These results indicate that more can be done to increase new process adoption. Polices

should be developed such that the positive levers are emphasized, and the neutral and

negative levers are either reshaped or replaced.

Stepping away from the ALCs for a minute, there is another interesting example of the

negative aspects of policy on a governmental program, and the policy changes

recommended by an outside party: the Columbia Shuttle Disaster. The Columbia

Accident Investigation Board concluded, in August 2003, that the disaster was the result

of many technical and organizational failures. In their recommendations to be completed

before a return to flight, they highlighted the need for better public safety policy and

scheduling policies that allow questions of safety to be adequately addressed (CAIB,

2003).

In the ensuing two years, NASA has worked to create and implement these new

policies, and was successful in returning to flight in July 2005. Also, during this flight,

new techniques were used to observe all possible difficulties with lift-off, and new

measures were taken in-flight to correct damage found. There was a new recognition that

something could be done during the mission to save lives, rather than waiting to fix the

problems after a return to Earth. Enterprise transformation within a government context

is possible, but difficult and demanding,

2.5 Methodology

This research is the result of an inductive study based on the lean enterprise

transformation efforts at the three US Air Force Air Logistics Centers. It was inductive

because I developed the list of capabilities after reviewing the above-cited literature, as

well as after spending time at each of the ALCs, observing them and their transformation

attempts, in real time.

My work is an extension of scheduled LAI engagements with the three sites, including:

* Case study work at Warner Robins (January 2004)

* EVSMA at Ogden (December 2003 to June 2004)

* EVSMA at Oklahoma City (May 2004 to August 2004)

* EVSMA at Warner Robins (April 2005 to May 2005)

EVSMA is the Enterprise Value Stream Mapping and Analysis Process (Nightingale &

Stanke, 2005) developed at LAI to jump-start the lean enterprise transformation process

at enterprises throughout the aerospace industry. The three ALCs present one alpha-test

(OO-ALC), one beta-test (OC-ALC), and one gamma-test (WR-ALC).

My first introduction to life at the ALCs was through the case study work completed at

WR-ALC in January 2004. I was part of a five-person team that traveled to WR-ALC in

order to study recent lean transformation efforts in different parts of the enterprise. (All

of the case studies can be found at http://lean.mit.edu/l.

Personally, I was responsible

for the case study of their lean efforts surrounding the Purchase Request process. This

study presented me with new ideas regarding the change management necessary for

successful implementation, as well as a broader, enterprise view of lean as this was not

happening on the manufacturing floor.

I next had the opportunity to study the ALCs and their transformation efforts through

direct observations during the EVSMA process. At OO-ALC, I saw only the last few

meetings, while I was present for eight out of nine of the meetings at OC-ALC and two

out of two meetings at WR-ALC. These meetings gave me good insight into the inner

workings of the leadership teams. I was able to observe their interactions, their

disagreements, and their methods of assigning group priorities. I interviewed leaders

outside the meeting to understand their thinking and their past experience with enterprise

change. These interviews and observations, combined with my literature review, allowed

me to identify some capabilities that they were missing.

I deviated slightly from open-ended interviews with the leadership team and select

change managers at WR-ALC. During these interviews, I administered a twelve-part

questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to introduce the twelve lean enterprise

change capabilities I had developed, and then question the individual regarding their

perception of the enterprise's current performance. In addition to recording precise

numerical responses, I also gave each respondent the opportunity to comment on my

questions. These comments proved quite useful for me in better understanding the

current state of lean enterprise transformation. Furthermore, after administering the

questionnaire, I asked each participant to perform a card sorting exercise. They were

asked to sort twelve cards, each printed with one lean enterprise change capability, into

two lists: first, to assess the current performance of the enterprise, starting from what they

do best and going to what they do worst; and second, to assess the future performance

needed in terms of what they need most to what they need least to make lean enterprise

transformation stick. The results of this questionnaire and sorting activity can be found

in Section 6.

All data collected were compiled, sorted, and classified when I returned to LAI. I

developed the list of twelve lean enterprise change capabilities through examination of

these data, organizational change literature, and the definitions included within LESAT

("Lean Enterprise Self Assessment Tool," 2001).

3

LEAN ENTERPRISE CHANGE CAPABILITIES..................

44

3.1

Introduction .............................................................................................................................

3.2

LESAT as a Preliminary Indicator .............................................................................................. 45

3.3

A Leadership Team with a Shared Mental Model................................

3.4

Planning and Implementation Process .................................................................................. 51

3.5

Balanced and Cascading System of Metrics ...................................................

3.6

Standardized Processes (and a Team to Track Them) ........................................

3.7

Compensation and Reward System ....................................................................................... 61

3.8

Developing and Deploying Vision and Mission ........................................................................

63

3.9

Communication and Public Relations Abilities ................................................

67

3.10

68

Change Management...........................................................

3.11

Cadre of Change Agents ......................................................................................................... 71

3.12

Context for Local Experimentation ............................................................................................. 72

3.13

Continued Learning and Self-Renewal ..................................................................................

3.14

Training and Education .......................................................................................................... 77

3.15

Conclusions ..............................................................................................................................

............

44

48

.......

55

57

75

79

3 Lean Enterprise change capabilities

3.1 Introduction

Analysis of the literature and incorporation of LESAT definitions and descriptions ("Lean

Enterprise Self Assessment Tool," 2001) with my own observations and field experience,

allowed me to create a list of lean enterprise change capabilities. All twelve of these

capabilities are necessary, but individually not sufficient, for successful initiation and

sustainment of lean enterprise transformation:

1. A leadership team with a shared mental model;

2. Planning and implementation process;

3. Balanced and cascading systems of metrics;

4. Standardized processes and a team to track them;

5. Compensation and reward system;

6. Developing and deploying vision and mission;

7. Communication and public relations abilities;

8. Change management;

9. Cadre of change agents;

10. Context for local experimentation;

11. Continued learning and self-renewal; and

12. Training and education.

Using this compiled list, any enterprise can be assessed according to the existence of

these capabilities, and predictions can be made regarding their chances for success.

Currently, there is no formal scale associated with maturity of these capabilities or their

state to determine readiness for lean enterprise transformation. Throughout the rest of

this thesis I will refer to current readiness levels in terms of low, medium, and high for

each capability.

3.2 LESA T as a PreliminaryIndicator

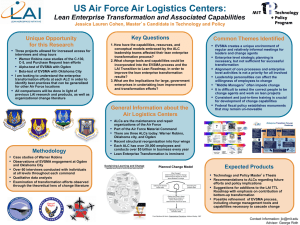

The Lean Enterprise Self Assessment Tool (LESAT) is a tool intended to appraise the

leanness of an enterprise, as well as its readiness for change ("Lean Enterprise Self

Assessment Tool," 2001). (The full document can be found at http://lean.mit.edu.) The

tool was designed by LAI representatives to complement other tools already developed

and in use, including the Enterprise Transition to Lean Roadmap (Figure 3.1). During the

development and research phases of these tools, academic, industry, and government

input was considered in order to make them as robust as possible. LESAT went through

alpha and beta testing between 1999 and 2001, and was released to the LAI consortium,

along with a facilitator's guide in 2001 (Hallam, 2003, Nightingale and Mize, 2002). The

assessment tool has also been translated into a version particularly suited for government

enterprises ("Government Lean Enterprise Self Assessment Tool," 2005, also found at

http://lean.mit.edu).

LESAT uses a five-point capability maturity matrix to measure performance. Assessors

are asked to gauge their enterprise according to both current performance or "as is" state,

as well as what they envision for future performance or "desired state." Throughout the

assessment, each lean practice and the related maturity levels are precisely defined. Also,

general descriptions of each maturity level are given at the beginning of each section in

order to maintain consistency across practices (Table 3.1). As compared with the lean

enterprise change capabilities defined below, a LESAT score of 1 to 2 corresponds to a

low maturity level, a LESAT score of 3 corresponds to a medium maturity level, and a

LESAT score of 4 to 5 corresponds to a high maturity level.

Maturity Level

1

General Description

Some awareness of this practice; sporadic improvement activities

may be underway in a few areas.

2

3

4

5

General awareness; informal approach deployed in a few areas with

varying degrees of effectiveness and sustainment.

A systematic approach/methodology deployed in varying stages

across most areas; facilitated with metrics; good sustainment.

On-going refinement and continuous improvement across the

enterprise; improvement gains are sustained.

Exceptional, well-defined, innovative approach is fully deployed

across the extended enterprise (across internal and external value

streams); recognized as best practice.

Table 3.1 LESAT Capability Maturity Levels - general descriptions ("Lean Enterprise

Self Assessment Tool," 2001).

The assessment tool is divided into three sections. This configuration allows different

elements of lean maturity to be highlighted and emphasized with particular questions.

The first section, "Lean Transformation/Leadership," assesses strategic integration,

leadership and commitment, value stream analysis and balancing, change management,

structure and systems, and lean transformation planning, execution and monitoring. The

outline of this section follows the LAI Transition to Lean Roadmap (Figure 3.1). The

second section, "Life Cycle Practices," examines enterprise level core processes

(including acquisition, program management, requirements definition, product/process

development, supply chain management, production, and distribution and support) and

key integrative practices. The third section, "Enabling Infrastructure," scrutinizes lean

organizational enablers (finance, information technology, human resources, and

environmental, health and safety factors) and lean process enablers (standardized

processes, common tools and systems, and variation reduction).

Long Term Cycle

Entry/Re-entry Cycle

I.BAdpt ea

Paadg

LC Focus on the

Initial

Lean

Value Stream

"Map Value Stream

"Internalize Vision

"Set Goals &Metrics

Decision to

Pursue

Enterprise

ransformation

I Detailed

Lan

'

-

Incentive

Align

Viain

Short Term Cycle

Detailed

o i o

M

L oeannProg

itorresIAc

0sn

4

-

Corrective

tion-

Lean

Transformation

Framework

'Create

. &Refine

insformation Plan

ýy

&Prioritize Activities

Ourtuoesteon

iitResources

eEducation &Training

Enterpriseea

jevelpDetiedPl

Iita ve

Ms

" mpemn LanAtiite

Enterprise

Level

10 Transformation

Plan

~

/

Figure 3.1 LAI's Enterprise Level Transition to Lean Roadmap.

Because LESAT was designed to assess "lean maturity" it is not organized to assess

enterprise change capabilities. However, there are parallel or related concepts for the

change capabilities in the leadership and enabling infrastructure sections of LESAT. To

help develop these connections between LESAT and the twelve change capabilities, and

use the LESAT scores to provide insight into the change capabilities, I will describe each

transformation capability and the associated LESAT section and question.

3.3 A Leadership Team with a Shared Mental Model

A leadership team with a shared mental model should embody the assumptions of both

Theory E (focus on economic value delivered) and Theory O (focus on development of

organizational capabilities), and should strive to balance the approaches suggested by

both theories (Beer & Nohria, 2000). The team must understand the interactions

throughout the organization, and have the capacity to optimize across the system, and

know that politically, as one employee stated, "Not everyone will win every day." The

EVSMA process can help develop this capability by encouraging honest discussion and

providing a forum for leadership communication, but it does not ensure that it will

persist.

This team must have one clear leader driving all efforts, but this leader should also be a

part of the team, and must share the same mental model. Everyone else should not be

expected to defer to the opinions of this leader all the time, but nor should team members

reject the opinions offered by the leader just out of hand. Everyone should be given the

opportunity to express innovative ideas free from judgment and pervasive criticism

(Isabella, 1990).

i I

i

1L

d

C

ed

Cd

4)"

cd

0 0

t 0 -4> 0 'AC

's

d

a 0 4.o

0

c

c~~

o 0

to 0

Cd

u

a)

.c

4).

'-4

0s

,

0U0

g

EI

d

-ovcr

cn

+.b)

v

o0

o w

cd

>

od

4

.)

"

b4-dý

>-

d

0

.

u

0

o

o

-k

o

.. CO

4

cddo

t-4

w 4.4.)

o

w~ A

W~

ot

vl,4

Ln

-

0a

~

0

.0

0

0,

od

w -4o

"

~ou1

0

oUU,*>

t

> 4-o

-4

-c

Cd

-4 W

cd

4

Ew

;..4 0

E4

Cd

4

*Cd

0

Cd

-S

0-

0

-1cd

Z

cqs

04

4-4

Cd

zz

5

to

L:L,;

0

=

d · d

ý

(

W

cd

-4

UPaQ:I >

4 cd

~

0

d

id

ý--4

C

0

tol

6

rt5

0.4 A4

0

rz)

c

-21"cc

Iz. q,

A shared mental model will enable this team to participate in strategic planning and

implementation processes on a more regular basis. They will be able to agree on the case

for action, identify their future state goals, and collectively create a transformation plan

that will allow victory.

The first section of LESAT discusses and describes qualities inherent in a leadership

team that shares drive and motivation. In particular, I believe TTL link I.B - Adopt Lean

Paradigm - best captures the shared understanding needed by a leadership team. Included

within this section are the practices and maturity levels captured in Table 3.2.

The EVSMA process can instigate the formal process of leadership education, as well as

provide an environment in which a consensus surrounding a commitment to lean

enterprise transformation could be built. A high maturity level for all of these practices

would include the ability to make lean thinking integral to leadership discussions and

events at any site and any time. In order to move forward with this capability, and with

lean enterprise transformation, an enterprise will have to strengthen its leadership

commitment, better communicate this commitment and enthusiasm to the workforce, and

show specific examples of lean improvements in leadership processes.

However, developing this capability is bigger than just "executive development" and

typical team building exercises. The team must actively share views and attitudes, and

they must understand how they can work together for the greater good of the enterprise.

These activities should not be seen as part of the lean initiative underway, but rather as a

foundation for overall successful management. This quality is captured in LESAT

practices I.B.1 and I.B3: leaders must actively work to educate themselves in lean

practices together, and create a new vision of the enterprise that they all believe in. High

maturity in these practices would indicate an enterprise leadership team ready to proceed

with lean enterprise transformation.

3.4 Planning and Implementation Process

A Planning and Implementation capability entails an efficient and effective process

which brings lean concepts and tools to the truly enterprise level. This process must

allow senior leaders, and others, to connect strategic planning to financial budgeting and

resource (people, time, and money) allocation all the way through operationalization of

ideas and efforts.

Up-front planning is important, but follow-through is critical. Many transformation

efforts get stuck when then cannot generate and then sustain quick wins, and when they

cannot link individual successes back to the larger strategic goals of the enterprise, such

that everyone can become excited (Kraatz & Zajac, 2001). There is a difference between

planning and acting, and the latter should not be automatically substituted for the former.

This capability will go hand-in-hand with the system of metrics capability, as that

capability will provide a way to track the effectiveness and efficiency of this planning

and implementation process.

The planning and implementation process capability is stressed throughout LESAT;

likenesses of this capability can be seen in all three sections. Those practices that best

illustrate this capability and its relationship to the leadership team necessary to take

advantage of an efficient and effective process are found in Section I, and highlighted in

Table 3.3.

Throughout the EVSMA process, leadership teams are challenged to include lean projects

and efforts in their strategic plans. Stakeholder analyses are completed, and the

knowledge generated through this analysis will allow teams to balance long-term and

short-term stakeholder objectives as they move forward with their transformation efforts.

An enterprise with low LESAT maturity must work to develop a model through which all

lean efforts can be coordinated and aligned such that they can avoid sub-optimizing the

systems. As maturity levels rise, they must strive to allow local managers and employees

to correct mistakes and enable fast corrective action. Continuous improvement must be a

priority for teams with low to medium maturity levels. Otherwise momentum can be lost,

and transformation may stall. Teams with high LESAT scores on all seven of these

measures will be able to demonstrate the capability of an effective and efficient planning

and implementation process.

4-4

U,

0

Q

•.•,•

4)

0

0

4

a CU

~j

c4

0

P"4

a

.)

a.

0

.

no

.5?IP

U

ok

Cd

~cis

"o

a.)

,u

9~.

4. o

o

C.)U,

'

U,

t

o

h

0

0

~~

B

Uf~ 1-4

1-4

Cd

C's

~ ~a.

.-

!

n

lu2

U,

B

.a

a

0

0

4-

0

o

0 1

00U-.

(L)

o,

1: Cd

P

o

0a 1e

0

a.) 0440

Pu

K

.)4

~*

0

a.)

Uo

o'g

M rE]Ia.)

PE

"o

F4

a

*D

-)Q

O

rl

a.)~ ~4bO

.0.

q*

*

F:

.C

.

~)

U

B4

.

b

U

0

1-4

U,

a.

U,

an

02

U,

=

S;o

-'

S

a.)

.

0

>o

0

00

0

3

A'S

bge

fg

o 2U

Cm

y

,U

·

04 Q

a.'

al.

c3

0

4)

0

u0

o2'-4 4Bn

13

a.)B

x

o.,4

o0

,d

o;4

o

cH

E

CA

3.5 Balanced and Cascading System of Metrics

A system of metrics should be designed such that it supports the strategic intentions of

the enterprise. The set should drive ideal behaviors at all levels, as opposed to behavior

devised purely to meet expectations. Ultimately, metrics should drive behavior that

results in the delivery of expected value to all stakeholders. Vikram Mahidar, another

LAI research assistant, has devised a graphical representation of the cascading nature of

an effective system of metrics (Figure 3.2).

--

Metric Cluster

I

Metric Set

I

N

Individual Metric

Figure 3.2 Conceptual design for the Lean Enterprise Performance Measurement System

(Mahidhar, 2005).

Quite importantly, everyone involved in collection of any data should understand the

rationale behind those metrics selected. This understanding will establish a sense of buyin from all employees. Also, if people recognize and respect the justification and

motivation for each measure, they may see a reduced incentive to "game the system" and

manipulate the way data are reported.

0

E

-o

*0

4Cfa

u

cl

Cf

C/

E

E-0,

At LAI, we subscribe to the idea that when it comes to enterprise level metrics, fewer are

better. Fewer metrics at the enterprise level allows for ease of reporting and ease of

problem solving (Mahidhar, 2005). This concept is also captured in LESAT (Table 3.4)

under practice I.C.4, but it is not expected until a level 3 maturity has been reached. This

indicates that enterprises with low capabilities are still able to instigate transformation

efforts, but must develop the capability further before success can be assured. Also,

metrics should not be used only for reporting and pure data collection: the data must be

used for learning and optimization across the enterprise. This is recognized by high

maturity enterprises, and is well defined in LESAT practices I.F.2 and I.G.2.

However, all of this does not imply a specific "balanced scorecard" approach (Kaplan &

Norton, 1996), but rather just the idea that metrics must be ingrained into the organization

and used to test and validate all improvement efforts, and used when making decisions at

all levels. For an enterprise to arrive at high maturity in this capability, this system of

metrics will become part of the new enterprise culture. Everyone must be trained to

appreciate metrics, and replace the "check the box" mentality of developing plans that are

never implemented and followed.

3.6 Standardized Processes (and a Team to Track Them)

Standardized processes and standard work are hallmarks of a truly lean enterprise. While

a new organization or enterprise can take the time to design effective and efficient

processes from scratch, this is virtually impossible for an existing and complex

enterprise. Because of this, any enterprise looking to embrace lean transformation must

work to document current processes, develop and standardizing new or existing process

where applicable, and continue to track these processes and their adoption by workers

and employees (Spear & Bowen, 1999). Standard processes allow workers the flexibility

to identify suspected problems, collect data as to the cause of this anomaly, and then

implement at solution as soon as possible. This greater flexibility allows change to occur

in that the "community of scientists" is free to work on local projects without approval

from higher levels.

The capability to standardize and track processes would likely involve a team or body of

people that would have a myriad of responsibilities:

* Identifying processes in which standard work could be designed and

implemented throughout the enterprise;

* Coordinating experts in every office or shop involved;

* Facilitating the design of the new work;

* Educating people on the new work;

* Providing coaching resources necessary for local leaders to train

people on the new work; and

* Collecting data for follow-up and documentation.

This team would also be a clearing-house for processes, such that in cases where

processes are similar, each team does not have to reinvent the wheel. They would also

manage all improvement practices, such that "lean" becomes an all-encompassing mindset, instead of just a set of tools to use. However this team should not be seen as the only

change agents in the picture. Instead, they can be viewed as supplementary to the

facilitators and coaches and change agents described below.

The capability encompassed by standardized processes and a team to track them is

codified within three questions in Section III of LESAT. This section focuses on

enterprise infrastructure necessary for successful lean enterprise transformation. In