FINDING COMMUNITY AT THE BOTTOM OF A PINT GLASS: COMMUNITIES

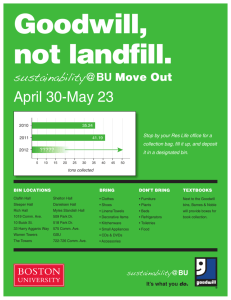

advertisement