LAUNCHING ALTERNATIVE REVENUE-GENERATING PROGRAMS: A CASE-STUDY OF EASTBROOK COMMUNITY SCHOOL‟S ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT

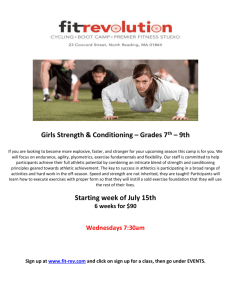

advertisement