School of Public & Nonprofit Administration Master of Public Administration Program

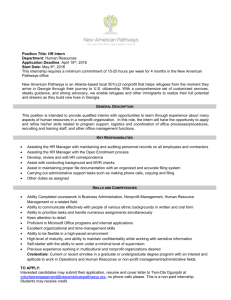

advertisement