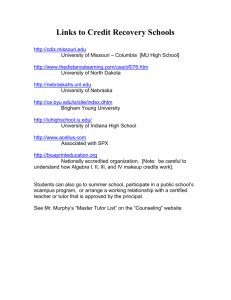

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

advertisement