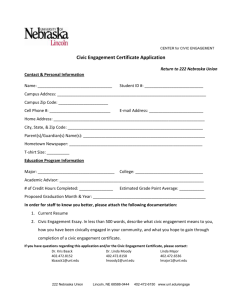

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

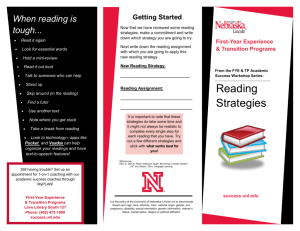

advertisement