Research Report City Fiscal Conditions in 2002

advertisement

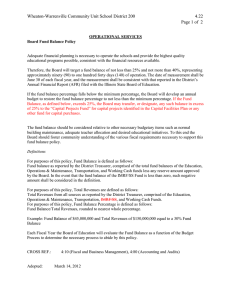

Research Report on America’s Cities City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 National League of Cities Copyright © 2002 National League of Cities Washington, D.C. 20004 Research Report Table of Contents Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .page iii Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .page v City Fiscal Conditions in 2001 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .page 1 Appendices Appendix A . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .page 23 Appendix B . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .page 26 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 Research Report City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 Ackowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the 308 respondents to this year’s fiscal survey. The commitment of these cities’ fiscal officers to this project is greatly appreciated. Data entry was provided by the Survey Research Laboratory of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs under the supervision of Jennifer Parsons, Assistant Director for Research Programs. Chris Hoene, Research Manager at NLC, guided this research endeavor from the redesign of the survey instrument through its administration phase and provided helpful and useful commentary on the analysis. Bill Barnes, Director of the Center for Research and Municipal Programs at NLC, provided helpful comments about the survey instrument and the final report. Christiana Brennan, Research Assistant at NLC, provided additional support in monitoring survey responses, conducting follow-up mailings and phone calls, and editing the final report. Michael A. Pagano August 2002 iii Research Report City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 Executive Summary Amid the current economic downturn, the fall of the stock market, and federal and state budget crises, fiscal conditions in America’s cities are also declining. 1 For the first time in a decade, the majority of city officials report that they are worse off financially than in the previous fiscal year. Since the recession that ended in 1993, more than half of city officials have annually reported being better able to meet financial needs in the current fiscal year than in the previous fiscal year. In 2002, the majority of officials report that their cities are worse off financially than in 2001. 2 On the revenue side, the decline in city fiscal conditions is being fueled largely by slower than expected growth in revenues from sales taxes, income taxes, and tourist-related taxes such as restaurant and hotel taxes. While city officials had predicted a slowing of the growth rate in these revenues, actual receipts between October 2001 and March 2002 (the post-September 11, 2001 period) were substantially below projections. On the expenditure side, public safety spending, rising health care costs, and infrastructure investment are fueling a steady rate of growth. Heightened demands for public safety expenditures after September 11, 2001 began to be apparent in early- to mid-2002 and are expected to continue to increase in the future. Aside from concerns about the health of the local economy, rising costs of health care and increased spending on infrastructure continue to be among the factors city officials cite as having the most negative impact on their local budgets. Concerns about slow revenue growth and increasing obligations can be seen in city officials’ expectations for their General Fund budgets.3 From 2001 to 2002, growth in General Fund expenditures was expected to increase slightly from its 2000-2001 level, while growth in General Fund revenues was expected to decline significantly. Expectations that these trends will continue into the future have local officials predicting a further worsening of conditions in 2003. Two-thirds of city officials believe that their city 1 “Cities” refers to municipal corporations. will be less able to address financial needs in fiscal year 2003. 2 All references to specific years are for fiscal Final figures for 2001 reveal that conditions in that year were probably the peak of the previous positive trend.4 In 2001, year-end balances, often called reserve funds or rainy-day funds, reached the highest point since the fiscal survey was first administered in 1985. Yet, city reserves are now threatened by significant erosion in the face of a worsening economy. As a result, there is cause for real concern that conditions will likely worsen in the near future. years. 3 The General Fund is the primary annual operating fund for cities. It is the largest fund, accounting for an average of 50 percent of total city revenues in 2001. 4 Many cities’ fiscal years ended prior to, or just after, September 11, 2001. v City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 1 The data for this report were derived from 308 Michael A. Pagano University of Illinois at Chicago The purposes of this study are to detail cities’ fiscal situations in 2002 and over the past decade and a half, to examine the effect of taxing authority and revenue diversity on revenue growth, to identify important factors affecting cities’ ability to balance budgets, and to delineate policy actions taken by cities in the past year that were designed to address their fiscal needs. 1 Overview of the Fiscal Environment Not since February 1998 has the Dow Jones Industrial Average fallen below the 8,000 mark as it did in July 2002, and the price of high-tech stocks on the NASDAQ retreated to 1997 levels. Not since Fiscal Year 1997 has the federal government incurred a budget deficit. The unemployment rate in June 2002 was 5.9 percent (down from 6.0 percent in April 2002), a level not seen since September 1994. 2 Per capita personal income increased in 2001 over 2000 levels by over $500 to $23,687 (constant 1996 dollars), a healthy increase compared to earlier years. 3 And while the prognosis for the long-term is for the national economy to regain its strength, short-term problems continue to beset nearly all sectors. 2001. 4 The cities’ fiscal The nation’s cities started feeling the economic slowdown in officers became less enthusiastic about their cities’ fiscal fortunes, projecting little or no real growth in revenues and ending balances for 2001 or 2002. Even the cautious pessimism of finance officers could not anticipate the bottom dropping out of the 1 respondents to a survey administered in March and April 2002 to all cities with populations exceeding 50,000 and to a sample of cities with populations between 10,000 and 50,000. The response rate was 29.1 percent (see Appendix A for a discussion of the methodology). In this report, the “municipal sector” refers to the sum of all responding cities’ financial data included in the survey. As a consequence, when reporting on general-fund revenues and general-fund expenditures for the “municipal sector,” it should be noted that those aggregate data are influenced by the relatively larger cities that have very large budgets and that deliver services to a preponderance of the nation’s cities’ residents. “Cities,” on the other hand, refers to municipal corporations. Therefore, when averages are presented for “cities” (as opposed to the “municipal sector”), the unit of analysis is the municipal corporation. Average city spending, for example, is equal to the sum of each city’s average spending level divided by the total number of responding cities. Thus, the contribution of a small city’s budgetary situation on the average statistic is weighed equally to the contribution of a large city’s. 2 U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics website, http://data.bls.gov/servlet/SurveyOutput Servlet?data_tool=latest_numbers&series_id= LFS21000000 3 U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts website: http://www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dn/ nipaweb/TableViewFixed.asp#Mid 4 City Fiscal Conditions in 2001 (Washington, DC: National League of Cities, July 2001). Research Report economy, albeit briefly, in response to the shock of September 11, 2001. 5 Not only was Wall Street closed for the first time due to a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, but the impact on retail sales sent many states’, counties’, and cities’ sales tax collections into a freefall. Quarterly state tax revenue figures declined in the July-September 2001 quarter (3rd Quarter 2001) by 3.1 percent, or 5.0 percent in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, and in the 4th Quarter by 2.7 percent, or 4.1 percent in real terms. 6 The economy failed to pick up the momentum in the new year and state sales-tax receipts declined in the 1st Quarter 2002 (January-March 2002) by 7.9 percent, or 9.5 percent in real terms, marking “the worse quarter of state tax revenue decline.” Revenue growth for governments depends in part on their authority to tax individual and corporate wealth and various parts of the economy. Most local governments are authorized to tax real estate, while others’ authority extends to taxing retail-sales transactions, personal property, or wages and salaries. Municipal corporations’ taxing authority is constrained by state constitutions and statutes. Revenue structures are more or less “responsive” to changes in the underlying economic base. Income tax revenue, because it is collected regularly and increases or decreases according to changes in wages and salaries, responds rather immediately to changes in economic circumstances. Sales tax receipts also respond to changes in consumer behavior, which in turn depends on income, needs, and confidence in the future income stream. Property tax revenues tend to be less immediately responsive to changes in the underlying economic base of a city because properties are not exchanged regularly and the value of property, as a consequence, tends to be estimated only occasionally. 5 Surveys of city officials taken shortly after the terrorist attack are reported in: Chris Hoene, “Cities Increase Security, Coordination; Worry About the Economy” Posted: October 22, 2001 on NLC’s website: http://www.nlc.org/nlc_org/site/newsroom/nations_ci ties_weekly/display.cfm?id=A70B94DA-4DD942FE-A23B8B890090333F ; Chris Hoene and Kyan Bishop, “Cities May Face $11 Billion Revenue Hit” Posted: November 12, 2001 on NLC’s website: http://www.nlc.org/nlc_org/site/newsroom/nations_ cities_weekly/display.cfm?id=976CA377-55D9447E-B2857AA7C88503F1 6 Nicholas W. Jenny, “Worst Quarter of State Tax Revenue Decline,” State Revenue Report, No. 48 (June 2002). The federal government and the states rely on one or both of the more elastic general tax sources, namely, the income tax and the sales tax. During the 1990s, an era of rapid economic growth in which both incomes and consumption increased, federal and state revenue collections increased at a very strong rate of growth. Without increasing tax rates, tax revenues surged for those governments that levy a sales or an income tax. Because economic growth is not capitalized entirely in real estate investment and land ownership, governments that rely more heavily on a property tax did not experience revenue growth as rapidly or immediately as the sales or income-tax governments during the 1990s. On the other hand, these property-tax levying governments are not expected to experience the sharp declines in revenue generation as the economy sputters and stalls. Unlike the quick responsiveness of sales and income tax revenue collections to surges in the underlying economy, the growth in property tax collections will change more slowly. Figure 1 presents the index in General Fund revenue growth for the federal government, state governments and municipal governments from 1988 to 2001 (1988=100). The federal government experienced considerable and prolonged growth in revenues, especially since 1996, until the economy slowed suddenly in 2001 and tax rates were reduced. The index for the federal government’s Federal Fund for 2000 was 236, meaning revenues grew 2 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 240 220 200 180 160 140 120 100 1988 Per Capita Income 100 100 GDP 100 Federal 100 State 100 Municipal 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 106 107 110 109 106 112 114 113 116 112 114 117 114 121 115 119 124 117 127 120 123 130 126 131 124 127 138 138 138 129 132 145 149 146 134 137 153 163 153 141 144 163 180 161 146 152 172 198 170 152 157 181 207 183 159 165 193 236 196 169 170 200 224 212 179 Figure 1: Federal, State, and Municipal General Fund Revenue Index (1988=100) 136 percent over their 1988 levels, but then actually dropped in 2001 to 224 due to reductions in the income tax rate and in personal income. States also experienced robust growth until 2001. 7 The index in 2001 for states was 212 or more than double the 1988 level. And although municipalities have experienced a slower overall growth rate in revenue generation than states and the federal government, the index in 2001 for municipalities’ General Fund increased to 179, an increase of nearly 6 percent over 2000 levels. Although access to the property tax by municipalities is ubiquitous, their revenue structures are anything but homogeneous. The revenue trendline for municipalities in Figure 1 masks the influence of diverse revenue structures. Nearly all municipalities are granted a property tax authority by their states, but authority to tax consumption (sales) or income is not universal. For example, of the approximately 555 US cities with populations greater than 50,000, roughly 34 percent have access to the property tax only, 8 percent have access to the income tax (in addition to having access to the property tax), and nearly 58 percent have some retail sales-taxing authority. 8 Besides nearly universal access to the income tax by municipalities in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky (and 20 or so in Michigan) most other municipalities with an income tax authority tend to be among a state’s largest (e.g., New York City, Kansas City, St. Louis, San Francisco) and are granted that authority by a special action of the state legislature. 9 3 7 General Fund revenue data are not tracked by NASBO, but expenditure data are. These expenditure data are used as reasonable estimates of General Fund revenue data. 8 Calculation by author. General taxing authority derived from Appendix A, Michael A. Pagano, City Fiscal Conditions in 1999 (Washington, DC: National League of Cities, 1999) and revised by the author. 9 “Local Income Taxes on Nonresidents in the Nation’s 25 Largest Cities,” memorandum from Nonna Noto, Congressional Research Service, March 12, 2002 (draft); Tracy Von Ins, “Some Cities Turning to Local Income Taxes for Revenue,” Nation’s Cities Weekly, July 9, 2001, p.1. Research Report Sales tax authority is granted to some or all cities in 28 states. In Oklahoma, cities’ general funds rely on the sales tax as the only source of general tax revenues. In the other states, municipalities’ sales tax revenues are supplemented with one or both of the other general tax revenues, namely the property tax and, when permitted by state law, the income tax. The predominant general tax revenue for some cities, then, is the property tax (e.g., Milwaukee, Portland, Buffalo, Boston), for others it’s the sales tax (e.g., Oklahoma City, Shreveport, Dallas), and for others the income tax (e.g., Columbus, Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Cleveland, Louisville, Cincinnati). The composition of municipalities’ General Funds is presented in Figure 2. Although the property tax does represent the largest piece of the General Fund pie (26%), the sales tax and the income tax components taken together amounted to only slightly less (21%) than the property tax element. Other tax revenue accounted for 14 percent of General Fund receipts in 2001. Financial Officers’ Assessments 9 “Local Income Taxes on Nonresidents in the Nation’s 25 Largest Cities,” memorandum from Nonna Noto, Congressional Research Service, March 12, 2002 (draft); Tracy Von Ins, “Some Cities Turning to Local Income Taxes for Revenue,” Nation’s Cities Weekly, July 9, 2001, p.1. Cities’ Chief Financial Officers were asked whether their cities were better able to address their financial needs in the current fiscal year (2002) than in the preceding year (2001). They were also asked for the predictions of the budgetary climate in the next fiscal year (2003). For the first time in ten years, more than half of the responding cities’ financial officers (55%) believed that their city was less able to meet financial needs in the current fiscal year compared to the previous year (Figure 3). This majority “negative” assessment is not significantly related to: Federal funds 2% State funds 13% All other revenues 13% Fees/Charges 11% Other taxes 14% Income tax 8% Property tax 26% Sales tax 13% Figure 2: Composition of municipalities’ General Funds. 4 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 a) taxing authority: finance officers in cities with access to only the property tax only reported that their cities’ financial condition is in worse shape in 2002 than in 2001 in the same proportion to cities that have access to either the income tax or the sales tax [Figure 4]); b) population size: 50 percent of the nation’s small cities (populations between 10,000 and 50,000) and a slightly larger percentages (58%) of larger cities (Figure 5) reported being worse off; or c) regional location: although, 61 percent of the nation’s Midwestern city officials noted the deteriorating financial condition of their cities compared with a smaller 49 percent of the nation’s Western city officials (Figure 6). When asked their assessment of their cities’ ability to meet financial needs the next fiscal year (2003) compared to the current fiscal year, there was a noticeable decline in the proportion of fiscal officers who registered a “better able” response compared to earlier years (Figure 7). Two of three (67%) financial officers predicted that their cities will be less able to address their financial needs in fiscal year 2003 than in 2002, compared to 54 percent who reached this same negative assessment last year and only 37 percent in 2000. This perception did not vary according to the general taxing authority of the city or the size of the city. However, 44 percent of the Southern cities felt that their cities’ financial condition in 2003 would be better than it was in 2002, while only 21 percent of the nation’s Northeastern cities and 24 percent of the Midwestern cities predicted a better fiscal situation. Figure 3: Percent of Cities that Are “Better Able/Less Able” to Meet Financial Needs This Year Than Last Year 80% 1997 1998 1999 2000 56% 45% -55% 1996 -44% 73% -27% 75% -25% 69% 68% 65% -32% 1995 -32% 1994 -35% -43% 54% -46% 1992 34% 22% 21% 1991 -66% -40% -78% -20% -79% 0% 33% 20% -63% Percent of Cities 40% 58% 60% -60% -80% 1990 1993 Less able Better able 5 2001 2002 Research Report Property Tax Cities N=82 -55% 44% Income Tax Cities N=29 -52% 45% Sales Tax Cities N=192 -60 % -54% -50% -40% 44% -30% -20% -10% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Percent of Cities Better able Less able Small Cities N=117 10,000-50,000 -50% Medium Cities N=88 50,000-100,000 Figure 5: Percent of Cities That Are “Better Able/ Less Able” to Meet Financial Needs This Year Than in Last Year By City Size 47% -55% 42% Large Cities N=76 100,000-300,000 -58% 41% Largest Cities N=26 300,000 -58% 42% -60 % -40% -20% 0% Percent of Cities Better able Western Cities N=85 -54% 44% Midwest Cities N=76 -61% 38% Northeast Cities N=26 -50% 43% -80 % -60 % -40% -20% 0% Percent of Cities Better able 6 20% 40% 60% Less able 48% -49% Southern Cities N=113 Figure 4: Percent of Cities That Are “Better Able/Less Able” to Meet Financial Needs This Year Than Last Year By Taxing Authority Less able 20% 40% 60% Figure 6: Percent of Cities That Are “Better Able/ Less Able” to Meet Financial Needs This Year Than in Last Year By Region City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 80% 61% 64% 63% -39% -36% -37% 1996 1997 1998 1999 33% 55% -45% 1995 -67% 53% -48% 1994 -54% 50% -50% -40% 49% -20% -51% 0% 29% 20% -72% Percent of Cities 40% 46% 60% -60% -80% 1993 Less able 2000 2001 Better able City Responses To The Fiscal Environment A set of 18 factors that could affect municipal budgets was presented to finance officers in the survey. They were asked to identify whether the factor had “increased” or “decreased” since FY2001 and whether the change had a “positive” or “negative” effect on the city’s fiscal profile. Figure 8 presents the results. Employee wages and health benefits increased in over 9 of 10 (94%) responding city officials, and more than 7 in 10 city officials identified increases in infrastructure needs (72%) and public safety needs (75%). While 44 percent of the respondents indicated that the health of the local economy increased, only 22 percent indicated it had decreased. In addition, 76 percent noted that the city tax base has increased during the past year – only eight percent noted a decrease. On a personnel issue, 58 percent of responding city officials indicated that costs associated with employee pensions increased over the previous year. One in four indicated that education needs (26%), and federal aid (25%) and state aid (25%) had increased over the previous year. At the same time, 33 percent indicated that state aid had decreased and 24 percent noted a drop in federal aid. Roughly one-third (31%) noted that federal environmental mandates had increased, while 27 percent noted an increase in state environmental mandates. Survey respondents were then asked their assessment as to whether those factors in Figure 8 had a “positive” or “negative” impact on the city’s budgetary capacity to meet city needs. Figure 9 presents the results. “Employee health benefits” topped the list of “negative” impacts with 88 percent of responding city officials citing it as a negative factor; close behind was “employee wages” at 82 percent. Other “negative” impact factors included public safety needs (69%), infrastructure needs (67%), prices and inflation (67%), and employ7 2002 Figure 7: Percent of Cities That Are “Better Able/Less Able” to Meet Financial Needs Next Year (2003) Than in Current Year Research Report ee pensions (57%). The “health of the local economy” was cited by 49 percent of city officials as having had a “negative” impact on the budget, and it was also cited by 22 percent of city officials as having had a “positive” impact. Seven in ten city officials (70%) noted that the “city’s tax base” had a positive impact on their ability to meet cities’ overall needs, while only eleven percent noted that it had a negative impact. An interesting paradox arises from a reading of Figure 8 and Figure 9. There appears to be a disconnect between the fiscal officers’ assessment of the change in their city’s tax base (76% registered an “increase” in the tax base and 70% noted that the impact was “positive”), while a much smaller 22 percent stated that the “economic health” of the underlying economy had increased. Yet, more than 4 in 10 city officials (44%), on the other hand, concluded that their cities’ “economic health” had decreased and 49 percent noted that the impact was negative. In other words, while the tax base appears to have expanded since the last fiscal year, the city’s economic health apparently did not improve. One reason for this seemingly ambiguous response is that the economic downturn that was noticeable early in the fiscal year accelerated toward the end of the fiscal year and nearly collapsed for several weeks after the terrorist attack of September 11th, an issue discussed later this report. Figure 8: Change in Selected Factors from FY 2001 When finance officers were asked to identify the three items that have had “the most negative impact” on the cities’ ability to meet city needs, important shifts from the previous few years became apparent (Figure 10). First, the rise in the importance and impact of “health benefits” placed it at the top of the “most negative factors” list. More city officials (64%) than at any time since this question has been asked (since 1992) 100% 90% Percentage of Cities 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% Health of local economy City tax base Fed non-enviro mandates Amount state aid Education needs St non-enviro mandates Amount federal aid State tax & expenditiures Human Serv needs Population State enviro mandates Fed enviro mandates Employee pensions Prices inflation Employee health benefits Public Safety needs Infrastructure needs 0% Employee wages 10% Increased 93.8% 72.1% 75.0% 91.9% 76.3% 58.1% 31.2% 26.9% 53.9% 48.1% 14.3% 25.3% 19.5% 25.6% 25.3% 11.0% 76.0% 21.8% Decreased 0.3% 1.3% 0.3% 1.0% 2.3% 1.8% 2.9% 2.3% 10.4% 1.3% 1.9% 24.0% 2.3% 1.3% 33.4% 1.6% 7.8% 43.8% 8 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 100% 90% Percentage of Cities 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% Health of local economy City tax base Fed non-enviro mandates Amount state aid Education needs St non-enviro mandates Amount federal aid State tax & expenditiures Human Serv needs Population State enviro mandates Fed enviro mandates Employee pensions Prices inflation Employee health benefits Public Safety needs Infrastructure needs 0% Employee wages 10% Increased 3.9% 3.2% 3.6% 1.9% 3.9% 7.5% 0.6% 1.0% 17.5% 2.9% 1.0% 23.7% 0.6% 1.9% 20.8% 1.0% 70.1% 22.4% Decreased 81.8% 66.9% 69.2% 88.0% 67.2 56.8% 63.0% 29.9% 34.1% 43.2% 24.4% 25.6% 22.4% 20.8% 39.9% 14.3% 11.1% 49.0% Figure 9: Impact of Selected Factors on FY 2002 Budgets and Their Ability to Meet Cities’ Overall Needs placed the problem of health benefit costs as the most important negative factor. A distant second was infrastructure needs cited by 36 percent of the respondents as among the “most negative”, but a clear fall from its nearly perennial number-one position. During the past decade, the larger-than-expected increases in city revenues, especially from sales tax receipts, have found their way into city capital spending plans. As cities have been able to address more infrastructure needs, the category has diminished in relative importance. Finally, the performance of the local economy was identified as among the “most negative” factors by one in four city officials, putting it at near the same level as the 1992-96 period. Revenue Actions 2001 The most common revenue action taken by cities in 2002 and in the previous 15 years was to increase fees and charges for services (Figure 11). Two of five cities (39%) increased levels of fees and charges (Figure 12). The most significant variation in this revenue action was by city size. While nearly half of the nation’s large and medium-sized cities (46% and 44%, respectively) raised user fees, a smaller percentage of the nation’s largest cities raised user fees (27%) (Table 1). One-fifth of all cities (21%) increased property taxes. Less than ten percent of the nation’s large cities raised the property tax, while more than one-fourth (27%) of the small cities 9 Research Report 70 63.6 Percentage of Cities 60 51.4 44.3 20 52.6 47.4 35.7 38.6 21.7 18.9 10 4 8.6 1993 1994 1995 1996 Infrastructure Figure 10: Percent of Cities Reporting Item Has Had Among the Most Negative Impacts on Budget 16.9 7.8 0 1992 25.2 27.3 24.4 23.2 36.1 31.6 26.4 27.7 55.1 49.2 44.3 32.9 29.3 55.5 51 41.1 42.1 40 30 55.3 52.9 50 1997 1998 5 2000 1999 Health Benefits 2001 2002 Local Economy 80 Percentage of Cities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1987 Increased Fees/Charges New Fees/Charges Incr'd Property Tax Rate Development Fees Other Tax Rates New Tax 58 23 38 13 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 62 34 42 22 9 10 60 30 43 18 8 12 73 43 39 28 13 8 78 47 38 26 21 20 52 28 31 15 8 8 49 23 30 16 12 7 48 23 30 16 12 7 47 20 28 10 6 5 39 15 23 13 7 3 32 17 21 18 6 2 29 16 19 12 6 3 31 18 22 22 6 1 32 20 21 17 8 4 35.4 16.2 21.6 17.4 5.9 2.6 39.3 18.2 20.8 18.8 4.3 1.9 Figure 11: Revenue Actions, 1987-2002 45% Percentage of Cities 40% 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Employee Property wages Tax Rate Increased Decreased 1.9% 39.3% 14.3% 20.8% Number of Fees Level of Impact Fees 1.9% 18.8% 1.9% 18.2% 10 Other Tax Rate Tax Base Sales Tax Rate 3.9% 4.3% 2.6% 3.6% 2.3% 3.9% Number of Other Taxes 2.6% 1.9% Income Tax Rate 0.3% 1.6% Figure 12: Revenue Actions in 2001 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 adopted this revenue action. Moreover, 14 percent of all city officials also reported decreases in property tax rates in 2002. Slightly less than one-fifth of all responding city officials increased the number or level of impact fees (19%) and increased the number of other fees or charges (18%) with little variation attributable to city size. Municipal Tax Rate Increases Since 1995, state governments have been reducing tax rates and fees, thus generating fewer revenues than they would have collected in the absence of such actions. State governments reduced revenues through tax and fee reductions by $300 million in the current fiscal year 2002, the smallest decrease in eight years. Nevertheless, since 1995, state governments have EXPENDITURE ACTIONS TOTAL Increased infrastructure spending Increased growth rate of operating spending Increased size of city workforce Increased city service levels Increased contracting out services Improved productivity leveles Increased interlocal agreements Reduced size of city workforce Reduced infrastructure spending Reduced growth rate of operating spending Reduced interlocal agreements Reduced city service levels Reduced productivity levels Reduced contracting out services Increased human service spending Decreased human service spending Increased public safety spending Decreased public safety spending Increased education spending Decreased education spending 47.4 47.7 38.3 23.1 17.9 34.7 21.8 12.3 9.4 14.6 2.3 2.9 0.6 2.9 43.5 2.6 72.7 1.3 13.6 1.6 REVENUE ACTIONS TOTAL Increased level of fees/charges Increased property tax rates Increased number/level of impact or development fees Increased number of other fees or charges Reduced property tax rates Increased tax base Increased rates of other taxes Increased sales tax rates Reduced tax base Increased number of other taxes Reduced rates of other taxes Reduced number/level of impact or development fees Increased income tax rates Reduced income tax rates Reduced sales tax rates Reduced level of fees/charges Reduced number of other fees or charges Reduced number of other taxes 39.3 20.8 18.8 18.2 14.3 3.6 3.9 3.9 2.6 2.6 4.2 1.9 0.3 1.6 2.3 1.9 1.9 1.9 Table 1: Actions That Cities Have Taken During the Past 12 Months LARGEST CITIES LARGE CITIES MEDIUM CITIES SMALL CITIES 300,000 100,000-300,000 50,000-100,000 10,000-50,000 46.2 38.5 38.5 19.2 11.5 50 23.1 26.9 15.4 30.8 0 3.8 0 3.8 26.9 3.8 76.9 0 15.4 0 50 47.4 46.1 27.6 14.5 40.8 21.1 14.5 11.8 18.4 0 3.9 0 3.9 55.3 2.6 80.3 2.6 17.1 3.9 50 51.1 44.3 21.6 18.2 34.1 22.7 11.4 6.8 12.5 2.3 2.3 1.1 0 46.6 2.3 76.1 1.1 12.5 1.1 44.4 47.9 29.1 22.2 21.4 28.2 21.4 8.5 8.5 10.3 4.3 2.6 0.9 4.3 37.6 2.6 65 0.9 12 0.9 LARGEST CITIES LARGE CITIES MEDIUM CITIES SMALL CITIES 300,000 100,000-300,000 50,000-100,000 10,000-50,000 26.9 23.1 15.4 19.2 15.4 3.8 7.7 7.7 0 3.8 3.8 3.8 0 7.7 0 3.8 0 0 46.1 9.2 25 22.4 17.1 5.3 3.9 1.3 1.3 1.3 1.3 2.6 0 1.3 1.3 0 0 1.3 11 44.3 22.7 19.3 21.6 9.1 2.3 5.7 4.5 3.4 5.7 5.7 1.1 0 1.1 5.7 2.3 4.5 1.1 34.2 26.5 15.4 12.8 16.2 3.4 2.6 4.3 3.4 0.9 4.3 1.7 0.9 0.9 0.9 2.6 1.7 3.4 Research Report reduced tax and fee rates generating $33 billion in tax and fee relief, even as recent reports indicate that states’ budgets could be in a $40 billion deficit. 10 Estimates from previous NLC surveys indicate that, in contrast, the “municipal sector” has raised net tax and fee rates each year since 1992 in response to their fiscal situations and in so doing positioned city budgets for years of declining or slow economic growth. City officials were asked to report whether tax and fee rates were increased, decreased, or maintained over the past year. Respondents were also asked to estimate the revenue-raising potential for each fiscal policy action. As a result of raising and lowering tax rates, net tax revenues in the responding cities were expected to increase by $392 million over the previous year. This estimate excludes new money generated as a result of natural increases in tax revenues due to a growing tax base or more efficient revenue collection methods. It includes net changes in revenue that are a direct result of increases and decreases in tax rates, a conscious fiscal policy decision of city officials. 10 National Association of State Budget This tax increase divided by the total number of inhabitants of all the responding city officials (42,887,879 people in 307 responding cities) yields an average increase in taxes of $9.15 per city resident. The Bureau of the Census estimates that approximately 140 million people live in cities with 10,000 or more inhabitants. Multiplying this number by the average amount of per capita tax increase ($9.15) yields approximately $1.28 billion of increased municipal sector tax revenues as a result of net changes in tax rates in 2002. Officers, Fiscal Survey of States, May 2002 http://www.nasbo.org Likewise, as a result of raising or lowering fees and charges or imposing new ones, the Millions of Current Dollars $20,000 $15,000 $10,000 $5,000 $0 ($5,000) ($10,000) 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Net Effect of State Revenue Changes Net Effect of Municipal Revenue Changes Figure 13: Net Revenue Effects of Changes to State and Municipal Tax Rates and Fees 12 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 net increase in fee revenue is expected to amount to $153 million for the responding cities. This is not the amount of user fee revenues that were generated through higher use. Rather, this is the estimated increase in user fee revenues that are due to deliberate policy decisions to raise and lower city user fees and charges or to adopt new fees and charges. If this net increase in user fees and charges is divided by the total number of inhabitants of all the responding cities, the average net increase in fees amounts to $3.57 per city resident. Again, assuming the responding cities are representative of all U.S. cities, the total amount of fees generated by these policy actions equals approximately $500 million in 2002. The net effect of changes in both tax rates and fees for 2002, then, has been to increase revenues by a total of $545 million for the responding cities. This amounts to an average of $12.72 per city resident for all the cities in the survey, or, if extrapolated to all U.S. cities over 10,000 population, the equivalent of approximately $1.78 billion for 2002 (Figure 13). Figure 14: Expenditure Actions in 2001 80% Percentage of Cities 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Decreased Increased Public Safety Spending Capital Spending Operating Spending Growth Rate Municipal Workforce 1.3% 72.7% 9.4% 47.4% 14.6% 47.7% 12.3% 38.3% Human Productivity Contracted Services Levels Out Spending Services 2.6% 43.5% 0.6% 34.7% 2.9% 17.9% Expenditure Actions 2001 Nearly three in four cities (73%) increased public safety spending in 2001 (Figure 14). Roughly half of all responding cities increased infrastructure spending (47%) and the growth rate in their operating budgets (48%) with little city-size variation (Table 1). Almost two in five (38%) of the city officials that responded increased the size of the city workforce, also with little variation by city size. Nearly one in four cities (23%) increased city service levels, 18 percent increased contracting out services, 35 percent improved productivity levels, and 22 percent increased inter-local agreements (all with little variation in these actions based on city size or location). Figure 15 presents city responses to 13 City Services Levels 2.9% 23.1% Number Education of Spending Interlocal Agreements 2.3% 21.8% 1.6% 13.6% Research Report 80 Percentage of Cities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1987 Reduce Operating Budget 57 Reduce Capital Spending 56 Contract Out 27 Reduce Employment 27 Reduce Service Levels 8 Interlocal Agreements Increased Productivity 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 47 39 31 21 8 38 34 30 19 4 50 38 39 23 9 72 47 39 38 18 72 61 30 36 12 69 55 38 38 15 24 36 61 44 39 22 12 24 32 49 30 35 18 9 24 30 33 23 22 17 8 28 31 9 12 28 16 4 18 24 5 4 26 10 1 24 39 6 7 28 9 1 27 46 5 7 28 8 3 23 47 4.5 8.1 28.5 9.9 2.4 24.3 42.9 14.6 9.4 17.9 12.3 2.9 21.8 34.7 Figure 15: Expenditure Actions, 1987-2002 31 questions on expenditure actions since 1987. Fewer city officials identified “increasing productivity” during the past twelve months than in the previous two years. And the percentage of city officials that identified “reducing the growth rate in operating spending” tripled (to 15%) from 2000 levels (5%). The action “reduced growth rate of operating spending” showed notable variation based upon city size in 2002, as it did in 2001. Only one in ten (10%) city officials from the nation’s small cities reported a reduction in the growth rate in operating spending, while a much larger 31 percent of city officials from the nation’s largest cities reported this same action. Variation by city size in the “increased human service spending” action was also significant. Although slightly more than two-fifths (44%) of total city officials reported this action, 27 percent of city officials in the largest cities, and 55 percent of city officials in the nation’s large cities reported increasing their human service spending. Growth in Revenues/Expenditures & Ending Balances Year-to-year growth in General-Fund revenue has been quite robust, especially since 1996. Figure 16 plots the year-to-year changes of both general-fund revenues and general-fund expenditures in current dollars. Between 1991 and 2001, the average annual increase in general-fund revenues was 4.4 percent and the average annual increase in general-fund expenditures was 4.3 percent. Since 1997, however, the growth rate in revenues has been a very robust 5.2 percent while spending averaged 5.0 percent. Controlling for the effects of inflation still presents a fairly strong financial portrait of cities’ revenue and spending in the recent past (Figure 17). Since 14 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 1991, constant-dollar general-fund revenues grew 1.8 percent per year and constant-dollar general-fund expenditures grew 1.7 percent per year. And the growth rate since 1997 was 2.4 percent for general-fund revenues and 2.2 percent for general-fund spending. The political pressure to meet increased public safety concerns, higher health insurance costs, increasing human service needs, and many other city needs led city fiscal officers’ to prepare general-fund budgets for FY2002 that increased spending by 5.6 percent, or 4.45 percent in constant dollars. The budgeted growth rate in current dollar spending is somewhat greater than the previous five-year average of five percent. Budgeted revenue growth for FY2002, on the other hand, is 1.2 percent, or virtually flat in constant dollars. Much of the reason for the no-growth revenue projections for FY2002 can be explained by the poor showing of sales-tax and income-tax collections in FY2001. Figure 18 presents the annual growth rate in general-fund tax receipts by revenue source. The annual growth in sales tax collections between 1995 and 2000 averaged a very strong 6.5 percent but then plunged to –2.3 percent in 2001 and is expected to increase only slightly in 2002 (0.8%). Income-tax revenues also grew at a fairly strong rate, though not nearly as strong as the sales-tax growth rate. (One reason that the growth rate in “income” taxes was not as strong as the federal income tax growth rate during this period is that practically none of the responding cities with the authority to levy an income tax can tax capital gains.) The 4.0 percent average annual increase in income-tax receipts between 1995 and 2000 fell to 2.8 percent in 2001 and is budgeted at only 1.2 percent in 2002. The important point for understanding the projected revenue growth rate for FY2002, then, is that sales-tax collections and income-tax collections are expected to change very little from the previous year, a year that for sales-tax collections actually witnessed a Figure 16: Change in GF Revenues and Expenditures (current dollars) 1.19% 1.0% 0.0% 1986 1993 1994 Change in Current Dollar Revenue (General Fund) 5.56% 6.20% 5.99% 5.82% 5.12% 1998 4.52% 5.50% 4.31% 3.48% 1997 1.90% 3.78% 3.72% 5.31% 6.32% 1992 3.87% 4.14% 1991 3.64% 3.24% 1990 2.0% 3.22% 1989 4.19% 3.64% 1988 3.44% 1987 3.0% 4.75% 7.55% 7.0% 5.30% 4.0% 5.98% 4.96% 5.0% 5.46% 6.0% 5.32% 4.86% 7.0% 7.06% 6.66% 8.0% 1995 1996 1999 2000 2001 2002 (budget) Change in Current Dollar Expenditures (General Fund) 15 Research Report 4.45% 3.58% 2.88% 0.09% 1.80% 1.59% 2.55% 1.58% 2.59% 1.14% 1.20% 1.76% 4.04% 3.02% 1.27% 0.60% 1.00% 0.66% 2.34% 1.79% 2.44% 0.56% 1.87% 1.00% 0.0% 0.75% 1.0% 1.43% 1.04% 0.59% 2.0% 3.00% 4.0% 3.0% 2.43% 4.0% 4.25% 3.84% 5.0% -0.66% -1.0% 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 Change in Constant Dollar Revenue (General Fund) 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 (budget) Change in Constant Dollar Expenditures(General Fund) Figure 17: Change in GF Revenues and Expenditures (constant dollars) 10% 6.1% 0.8% 1.2% 2.8% -2% Figure 18: Year-to-Year Change in General Fund Tax Receipts 5.0% 5.8% 4.8% 4.6% 3.3% 5.5% 4.0% 5.9% 4.0% 5.4% -2.3% 0% 3.2% 2.2% 2% 3.6% 4% 5.9% 6% 7.7% 7.8% 8% -4% 1995-96 (est) 1996-97 Sales Tax Collections 1997-98 1998-99 Income Tax Collections 1999-2000 2000-01 2001-02 (budget) Property Tax Collections (all cities) decline in receipts. The good news is that property-tax collections, which averaged 4.2 percent growth between 1995 and 2000, continued to increase in 2001 at a very robust rate (5.0%) and are expected to increase in 2002 by an even stronger 6.1 percent rate. Ending Balances Cities operate under balance-budget requirements, meaning that cities almost always plan on ending the fiscal year with a surplus. This surplus, which is referred to as a “carryover balance” or a “reserve,” becomes available revenue for the next fiscal year. Reserves are planned for a variety of purposes, including the need to store funds in antic16 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 ipation of an economic downturn and declining revenues. Between 1993 and 2000, cities’ ending balances continued to build as the underlying economic bases of cities expanded rapidly. Indeed, the actual growth rate in revenues for most cities exceeded the budgeted or predicted growth rate, allowing cities to not only build up their savings but also to meet other needs. Among the list of expanding needs that cities have long identified is infrastructure or capital assets. The growth rate in spending on infrastructure between 1994 and 2000 far surpassed the growth rate in city operating spending. And the principal fuel for the explosive growth in capital spending was the unexpected accumulation of tax revenues resulting from economic expansion. A plurality of cities, according to survey respondents, has created “reserve” or “endingbalance” goals for their general funds (Figure 19). A substantial majority of cities either have an “official” ending balance or reserve goal (45%) or a “generally recognized” goal (25%) that they try to reach. Twenty percent of the responding cities follow an “informal” reserve goal policy, while fewer than one in ten (7%) do not have a reserve policy (3% did not answer the question). The survey asked city officials to indicate the dollar value of their cities’ official or “generally accepted” ending balances. Three-fourths of the 251 city officials responding to this question exceeded their cities’ ending-balance goals in 2001, while 15 percent fell below their goal. This latter group of 38 cities missed their target by $171 million, while the former group of 190 cities exceeded their target by $1.6 billion. In 2002, a smaller percentage (60%) of cities are expected to exceed their ending-balance goals. The average ending balance for the nation’s largest cities was $85.6 million in 2001, and $31.8 million for cities with populations between 100,000 and 300,000 (Figure 20). The nation’s small cities (10,000-50,000 population) averaged $5.6 million ending balances, while the medium cities (50,000-100,000 population) averaged $13.5 million. The ending balance goal for the largest cities was $35.9 million, indicating that the largest cities’ average ending balance exceeded the actual goal by $49.7 million on average. The ending balance goal for the large cities (100,000-300,000 population) was $19.6 million. The average large city exceeded the goal by $12.2 million. The ending balance goal for medium cities was Figure 19: Ending Balance Goal Policies, 2002 No goal 7% Unofficial, but generally recognized goal 25% 3% Official ending balance goal 45% Informal goal 20% 17 Research Report $7.7 million, which places the actual ending balances $5.8 million over the goal. And the small cities average ending balance of $5.6 million exceeded the goal of $3.5 million by $2.1 million. The municipal sector’s aggregate ending balance as a percentage of expenditures in 2001 increased to 19.1 percent, its highest point since the fiscal survey was first administered in 1985 (Figure 21). Only once during the series have cities’ budgeted ending balances exceeded the actual ending balances, and that was in 1992. Since then, budgeted ending balances have been generally within 1-3 percentage points of the actual ending balances. In August 2002, it is difficult to understand how city fiscal conditions in FY2001 could have been so strong. Yet, several issues are worth noting. First, nearly 40 percent of all cities end their fiscal years on June 30, which was prior to the September 11th terrorist attacks and the rapid decline in retail sales and tourism. Many other cities end their fiscal years on September 30, only a short time after the attacks and before these cities would have been able to feel the fiscal impacts. The data that is presented herein for a fiscal year does not discriminate between those cities whose fiscal years end June 30th and those that end December 31st or September 30th or April 30th. Consequently, the annual revenue and expenditure cycle for this fiscal report is not the same for all responding cities. Second, the accounting scandals of early 2002 in the private sector and the enormous shock of stock price collapses in June and July were most likely not anticipated or incorporated in FY2002 budget forecasts. The resulting declines in consumer confidence and purchasing power have now placed cities’ fiscal health in a more precarious position. Even though ending balances are at their highest point since data were first collected 18 years ago, there is cause for real concern about the fiscal health of cities. Because of the confluence of the declining economy and the terrorist attacks, this year’s report probes into their revenue impacts. $85,589 $80,000 $78,141 $73,713 ($000) $60,000 $40,000 $28,934 $20,000 $11.832 $5,343 $31,776 $33,299 $13,448 $12,650 $5,422 $5,637 $0 Figure 20: Average Ending Balance by City Size 18 Ending Balance 2000 Ending Balance 2001 Small Large Medium Ending Balance 2002 (budget) Largest City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 20.0 18.0 16.2 16.1 15.0 15.0 11.5 12.3 13.4 10.0 9.0 10.3 9.6 17.1 15.7 12.7 12.2 11.1 18.5 18.3 19.1 11.6 13.2 10.5 14.1 12.0 12.3 12.2 8.9 9.8 16.9 16.6 17.2 15.3 12.2 10.5 5.0 0.0 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Actual Ending Balance Budgeted Ending Balance Figure 21: Ending Balances as a Percentage of Expenditures (General Fund) Recession and 9-11 If city officials were anticipating a decline in certain revenues, one would expect forecasts to capture those declines. Indications that the economy was cooling down were well known by late 2000 and early 2001. But, no one predicted the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, DC on September 11th, 2001. Yet for many cities the revenue implications were obvious. Therefore, to separate the twin effects of recession and terrorist attack, we requested quarterly budgeted and actual data for four revenue sources. The data series for quarterly “budgeted amounts” and “actuals” began in the 4th Quarter of 2000 (October-December 2000) and continued through the 1st Quarter of 2002 (January-March 2002). The survey requested city officials to provide quarterly budgeted and actual collections of (1) property tax revenues, (2) sales tax revenues, (3) lodging, restaurant, amusement, and other tourist-related tax revenues, and (4) income tax revenues for the six quarters beginning with October 1, 2000 and ending March 31, 2002. Responding to the cooling economy, fiscal officers projected slow property-tax revenue growth during those six quarters, October 2000 through April 2002. Because property values and property tax collections tend to change marginally from year to year and do not respond to economic shifts as rapidly as sales, income, or tourist tax receipts, property-tax collection forecasts tend to be fairly reliable and accurate. For example, between October 2000 and March 2001, city officials that provided data on their budgeted property tax collections and actual property tax collections expected to collected $10.4 billion and actually collected $10.3 billion. Actual property tax collections for the six quarters, then, are 99 percent of budgeted or projected property tax collections (Figure 22). 19 Research Report Sales tax and tourist tax revenues, on the other hand, respond to underlying market factors immediately. A downturn in the economy reduces consumer confidence, which in turn tends to push consumer spending down. Since sales tax collections do not lag changes in the underlying economic base of a city, budget officials’ predictions of the state of the economy four or six quarters into the future tend not to be as accurate as their predictions for property tax collections. The same can be said of “tourist” taxes, which include lodging, restaurant, and amusement taxes. For the responding cities, the six-quarter accuracy for sales tax collections amounted to 97 percent of the budgeted amount and for tourist tax collections it was 91 percent. Forecasts of income tax receipts fared the poorest; actual collections were only 90 percent of budgeted amounts. Figure 23 presents the quarter-by-quarter comparisons between “actual” revenue collections and budgeted amounts. Between the 4th Quarter 2000 and the 3rd Quarter 2001, actual collections were roughly within 10 percent of projected collections. During the 4th Quarter 2001 (October-December), actual collections for tourist-related taxes fell to 89 percent of budgeted amounts then to 82 percent during the first quarter of 2002 (January-March). Given the fairly accurate prediction of quarterly “tourist” tax revenues for the first four quarters of the study period, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the substantial and widening gap between actual and budgeted tourist tax revenues for the last two quarters (October 2001 through March 2002) are related to the terrorist attacks and the subsequent decline in the tourist industry. What is also apparent from Figure 23 is that actual sales tax collections were between 98 percent and 102 percent of the predicted levels for the first three quarters of the study period. But for the next three periods, including the post-September 11th quarter, actual sales-tax collections were below budgeted amounts by about the same amount, 92-93 percent. 100.0% 98.0% 98.9% 96.0% 96.6% 94.0% 92.0% 90.0% 89.7% 89.7% 88.0% 86.0% 84.0% Property Tax Sales Tax Income Tax Tourist Tax Figure 22: Six-Quarter Forecast Accuracy (Actual Revenue Collections as a % of Budgeted Receipts) 20 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 Nevertheless, tourist tax revenues do not constitute a large share of municipal revenues, even as they are very important to several of the nation’s tourist destinations. Sales-tax revenues, on the other hand, amount to a very large share. The revenue data presented in Figure 24 are derived from those survey respondents that could provide both budgeted and actual data for all six quarters in the study period. Because more than half of all cities are authorized to impose a sales tax, the number of usable surveys from these cities resulted in a significant number (N=149). Based on the responses from the 149 sales-tax cities who could provide quarterly actual and estimated revenue data, the devastating impact of both the post-September 11th attack and the worsening economy pushed sales tax revenues to $77 million, then $82 million and finally $96 million below budgeted amounts, for a total of $286 million below projects for the four quarters ending March 31, 2002. Although the foregone revenues in Figure 24 are large, it should be noted that the budgeted amounts were not based on optimistic economic scenarios. Fiscal officers projected quite conservatively during this period, an important consideration given the very rapid growth in sales-tax collections in the preceding 4-5 years. For example, as Figure 25 depicts, fiscal officers budgeted for sales tax collections in the 1st Quarter of 2001 to be on average 3.4 percent more than the 4th Quarter of 2000 and only 0.1 percent more in the 2nd Quarter of 2001 than in the 1st. The budgeted amounts actually declined during the 3rd Quarter of 2001 and increased by 2.1 percent in the 4th Quarter and another 2.6 percent in the 1st Quarter of 2002. In other words, fiscal officers expected the late spring and summer months of 2001 to be fairly flat in terms of sales-tax collections but 105.0% 104.1% 104.1% 102.2% 100.7% 100.0% 98.1% 100.9% 97.7% 95.0% 95.1% 97.5% 93.7% 95.7% 92.3% 94.3% 93.4% 90.0% 89.3% 88.6% 85.0% 81.5% 80.0% 4th Q 2000 1st Q 2001 (Oct.-Dec.) Sales Tax (N=149) 2nd Q 2001 3rd Q 2001 Tourist Tax (N=127) 4th Q 2001 Income Tax (N=29) Figure 23: Actual Revenue Collections as a Percentage of Budgeted Receipts 21 1st Q 2002 (Jan.-Mar.) Research Report then pick up again for the Thanksgiving/Christmas season (4th Quarter). In actuality, however, sales-tax collections increased by 4.7 percent in the first quarter of 2001 but then dropped to 95 percent for the next two quarters. Actual sales tax receipts in the 4th Quarter 2001 did increase by 1.7 percent but then actually declined, albeit slightly, in the 1st Quarter 2002. $5,800 $10,840 $5,080 $20,000 $10,905 $40,000 $3,682 $27,386 The twin impacts of the deteriorating economic base, especially in consumption, tourism, and income (employment), and the heightened demands for public safety expenditures after 9-11-01 have become more apparent by early- to mid-2002. Although cities’ ending-balances reached very high levels by the end of FY2001, they are threatened by significant erosion in the face of a worsening economy. Cities’ access to the property tax, which does not change significantly in response to rapidly worsening (or improving) economic conditions, and cities’ substantial ending balances will most likely cushion the landing in the short term. Indeed, the ability to weather at least a shortterm economic decline is the hallmark of city fiscal policies that advocate substantial ending balances and balanced revenue structures. $(100,000) Fourth Quarter 2000 First Quarter 2001 (Jan-Mar 2001) Sales Tax Revenues (Actual-Budget) (N=149) Second Quarter 2001 Third Quarter 2001 Tourist Tax Revenues (Actual-Budget) (N=127) $22,040) $(25,055) $(24,283) Fourth Quarter 2001 $(96,679) $(77,440) $(80,000) $(16,184) $(52,393) $(30,688) $(60,000) $(82,679) $(77,440) $(2.856) $(28,105) $(20,000) $(40,000) $(2,730) $- First Quarter 2002 (Jan-Mar 2002) Income Tax Collections (Actual-Budget) (N=29) Figure 24: Difference Between Actual Revenue Collections and Budgeted Revenues (by Quarter) ($000) 22 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 APPENDIX A Methodology This 2002 report on city fiscal conditions is based on a national mail survey of finance officers in U.S. cities during March and April 2002. Survey data for this report are taken from the 308 city officials that responded to the mail survey, for a response rate of 29 percent (see Appendix B for a list of all responding city officials), allowing us to generalize for all cities with populations over 10,000. In March and April 2002, NLC sent surveys to all cities with populations greater than 50,000 and, using established sampling techniques, to a randomly generated sample of 520 cities with populations between 10,000 and 50,000. Questionnaires were mailed to 1,060 cities. They were returned to the Survey Research Laboratory, College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs, University of Illinois at Chicago, 412 South Peoria Street, Chicago, IL 60607, where they were compiled and coded and the data were put into computer-readable format (see Appendix C). The number of usable responses totaled 308, for a response rate of 29 percent. The response rate was higher for the larger cities than for smaller cities. 23 of the 55 largest cities (>300,000 population), or 42 percent, responded as did 76 of 155 cities, or 49 percent, in the larger city category (100,000-299,999 population). More than a quarter (26%) of the medium-sized cities (50,000-99,999 population) responded, or 88 of 338. And 119, or 23 percent, of the remaining cities that were sent surveys returned the form. Cities that responded to the survey are listed in Appendix A. The responses received allow us to generalize about all cities with populations of 10,000 or more. Due to the lower response rates from smaller cities and cities in the Northeast (16% response rate), any conclusions regarding cities remain tentative. Population groupings in this report are based on Census data. The “largest” cities are TABLE A-1 CITY POPULATION NUMBER OF CITIES IN THIS CLASS NUMBER OF SURVEYS SENT NUMBERS RETURNED RESPONSE RATE >300,000 55 55 23 41.8 percent 100,000-299,999 155 155 76 49.0 percent 50,000-99,999 338 338 88 26.0 percent 10,000-49,999 2,041 512 119 23.2 percent unknown 1 TOTAL 2.589 1,060 307 29.1 percent * All cities with populations greater than 50,000 were mailed surveys, and a random sample of cities between 10,000 and 50,000 were selected and mailed surveys. Table A-1: Cities Surveyed in 2002 and Response Rate By City Size* 23 Research Report defined as those with populations of 300,000 or more; “large” cities have between 100,000 and 299,999; “medium” cities between 50,000 and 99,999; and “small” cities have populations of 10,000-49,999. It should be remembered that the number and scope of governmental functions influence both revenues and expenditures. For example, many New England cities are responsible not only for general government functions but also for public education. Some cities are required by their states to assume more social welfare responsibilities than other cities. Some assume traditional county functions. Cities also vary according to their revenue-generating authority. Some states, notably Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania, allow their municipalities to tax earnings and income. Other cities, notably those in Colorado, Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, depend heavily on sales tax revenues. Moreover, state laws may require cities to account for funds in a manner that varies from state to state. Therefore, much of the statistical data presented herein must also be understood within the context of cross-state variation in tax authority, functional responsibility, and state laws. City taxing authority, functional responsibility, and accounting systems vary across the states. The dollar amounts presented in this report are in either current or constant dollars. Nominal dollars are deflated using the state and local government implicit price deflators. The survey asked for the following statistical data for fiscal years ending in 2000, 2001, and 2002: 13 FEDERAL AND STATE AID; REVENUE COMPOSITION of the city’s General Fund (property tax revenue, sales tax revenue, income tax revenue, other local taxes, fees and charges, state funds, federal funds, all other revenue); LONG-TERM G.O. DEBT OUTSTANDING and LONG-TERM REVENUE DEBT OUTSTANDING; PRINCIPAL AND INTEREST PAYMENTS ON G.O. DEBT; COMBINED FUNDS BUDGET; and CAPITAL SPENDING. The survey also asked for financial data for 2000-01 on the amount of ADDITIONAL CITY REVENUE the city generated during the past year as a result of raising tax rates and of raising fees and charges. 13 Most cities end their fiscal year on June 30 or December 31; a few cities end their fiscal years in April and September. As a result, most of the data requested in the survey are the legislatively approved estimates for the 2002 fiscal year. Data for previous years are actual or preliminary actual. City finance officials were also asked to provide data on their city’s GENERAL FUND. The General Fund is the largest fund of all cities accounting for an average of 49.8 percent of total city revenues in 2001, according to the survey respondents. And this statistic remains remarkably stable despite differences in city size. The General Fund accounts for approximately 45.9 percent of the total city budgets of the responding cities nation’s largest cities (defined as cities with populations greater than 300,000), 47.9 percent of the total budget of large cities (cities between 100,000 and 299,999), 47.6 percent of the total budget of medium-sized cities (cities between 50,000 and 99,999), and 53.8 percent of the total budget of small cities (cities between 10,000 and 49,999). 24 City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 The following were requested: • Beginning balance: These are the resources with which the city’s General Fund begins the year. If the city’s General Fund were a personal checking account, this would be roughly equivalent to the balance carried forward from the previous month. • Revenues (and transfers in): This is the grand total of all taxes, fees, charges, federal and state grants, and other monies deposited into the General Fund. While revenues are generally recurring items, the “transfers into general fund” also lumped into this item probably are not. These transfers occur when, for a variety of reasons, a city brings funds from one of its other specialized funds into the General Fund. • Expenditures (and transfers out): This is the total of all spending by the city’s General Fund and may include both operating and capital spending. Transfers out of the General Fund to other funds are also included here. • Ending balance: This is defined as the resources with which the city’s General Fund is left at the end of the year. The ending balance of one year becomes the beginning balance of the next. The ending balance is easily calculated as: Beginning Balance + Revenues - Expenditures = Ending Balance • Reserves: This is defined as the portion of ending balances that cities have earmarked for a capital project or for any other purpose, rendering those funds unavailable for general-purpose spending. Cities were also asked to identify which of a list of 19 possible fiscal policy actions were taken during the 12 months prior to receiving the survey (April 2001 through April 2002), how many of a list of 18 factors inhibited or helped the city’s ability to balance its budget, what three factors most adversely affected city revenues and city expenditures, what three factors most positively affected city revenues and city expenditures, whether the city is better able or less able to meet its financial needs in 2002 compared with the previous year, and whether the city will be better able or less able to meet its financial needs in 2003 compared with 2002. For this report, regional analysis is based on the Bureau of the Census’ definition of regions: NORTHEAST MIDWEST SOUTH WEST Connecticut Maine Massachusetts New Hampshire New Jersey New York Pennsylvania Rhode Island Vermont Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Michigan Minnesota Missouri Nebraska North Dakota Ohio South Dakota Wisconsin Alabama Arkansas Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Mississippi North Carolina Oklahoma South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia West Virginia Alaska Arizona California Colorado Hawaii Idaho Montana Nevada New Mexico Oregon Utah Washington Wyoming 25 Research Report APPENDIX B Responding Cities Torrence CA Vista CA Yorba Linda CA Concord CA Davis CA Fremont CA Los Angeles CA Norwalk CA Oxnard CA Palmdale CA PLeasant Hill CA Rialto Santee CA Simi Valley CA Danville CA Upland CA Vacaville CA Walnut Creek CA Watsonville CA Whittier CA Windsor CA Boulder CO Brighton CO Fort Collins CO Lakewood CO Longmont CO Colorado Springs CO Ansonia CT New Haven CT Cheshire CT West Hartford CT Boca Raton FL Cape Coral FL Coconut Creek FL Coral Springs FL Fort Lauderdale FL Gulfpoint FL Greenacres FL Inverness FL North Miami FL Pembroke Pines FL Pompano Beach FL Tampa FL Venice FL Palm Bay FL Sweetwater FL Royal Palm Beach FL Wellington FL Albany GA Savannah GA Juneau AK Montgomery AL Dothan AL Mobile AL Selma AL Fayetteville AR Fort Smith AR Little Rock AR Chandler AZ Peoria AZ Phoenix AZ Scottsdale AZ Lake Havasu City AZ Carlsbad CA Anaheim CA Bakersfield CA Bellflower CA Berkeley CA Burbank CA Camarillo CA Chula Vista CA El Segundo CA Fairfield CA Fullerton CA Hermosa Beach CA Irvine CA La Mesa CA Lakewood CA Lodi CA Martinez CA Milpitas CA Montebello CA Monterey Park CA Moreno Valley CA Mountain View CA Orange CA Pittsburg CA Porterville CA Redding CA Redondo Beach CA Riverside CA Salinas CA San Bruno CA San Diego CA San Leandro CA Santa Barbara CA Santa Clara CA Santa Maria CA Sunnyvale CA 26 Burlington IA Davenport IA Mason City IA Ottumwa IA Sioux City IA Dubuque IA Iowa City IA Boise ID Bloomington IL Evanston IL Naperville IL Peoria IL Wheaton IL Mount Prospect IL Rolling Meadows IL Bloomingdale IL Bolingrook IL Franklin Park IL Oak Lawn IL Orland Park IL Woodridge IL East Chicago IN Evansville IN Terre Haute IN Atchinson KS Leawood KS Kansas City KS Topeka KS Lexington KY Alexandria LA Baton Rouge LA Eunice LA Monroe LA Sidell LA Lake Charles LA Shrevport LA Athol MA Bedford MA Boston MA Newburyport MA Arlington MA Annapolis MD Greenbelt MD Newcarrollton MD Lewiston ME Cadillac MI Farmington MI Ferndale MI Oak Park MI City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 Sterling Heights MI Detroit MI Grand Rapids MI Kalamazoo MI Lansing MI Pontiac MI Bemidji MN Bloomington MN Austin MN Moorhead MN Duluth MN Belton MO Bellefontaine Neighors MO Independence MO Joplin MO Kansas City MO Kirksville MO St Joseph MO St. Louis MO Springfield MO Warrensburg MO Greenville MS Gulfport MS Billings MT Great Falls MT Ashville NC Havelock NC Lexington NC Monroe NC Salisbury NC Winston-Salem NC Raleigh NC Reidsville NC Cary NC Matthews NC Lincoln NE Omaha NE Portsmouth NH New Providence NJ South Brunswick Twp NJ Hamilton NJ Piscataway NJ Trenton NJ Albuquerque NM Santa Fe NM Clovis NM Las Vegas NV Buffalo NY Lackawanna NY New Rochelle NY Oswego NY Akron OH Bedford OH Berea OH Brook Park OH Brooklyn OH Brunkswick OH Euclid OH Fairview Park OH Fremont OH Mansfield OH Seven Hills OH Springfield OH Toledo OH Wilmington OH Cleveland heights OH Columbus OH Fairfield OH Perrysburg OH Tiffini OH Warren OH Bartlesville OK Chickasha OK McAlester OK Midwest City OK Norman OK Ponca City OK Shawnee OK Moore OK Salem OR Eugene OR Gresham OR Portland OR Aston PA Bethlahem PA Columbia PA Pittsburgh PA Mechanicsburg PA Philadelphia PA Barrington RI Greenville SC North Charleston SC Athens TN Springfield TN Memphis TN Millington TN Arlington TX Austin TX Balch Springs TX Beaumont TX Brownsville TX Burleson TX Carrollton TX Coppell TX Corpus Christi TX Denton TX League City TX Lubbock TX McKinny TX Mission TX Richardson TX Victoria TX Wichita Falls TX Dallas TX Fort Worth TX Gainesville TX Garland TX Houston TX Irving TX Laredo TX Lewisville TX Longview TX McAllen TX Midland TX Odessa TX Pasadena TX Plano TX Robstown TX San Antonio TX Tyler TX University Park TX Waco TX Layton UT Sandy UT West Valley City UT Alexandria VA Radford VA Richmond VA Roanoke VA Suffolk VA Danville VA Newport News VA Norfolk VA Virginia Beach VA South Burlington VT Salt Lake City VT Bellingham WA Bellvue WA Kelso WA Spokane WA Tacoma WA Brookfield WI Greenfield WI West Bend WI Manitowoc WI Milwaukee WI New Berlin WI Brown Deer WI 27 Research Report City Fiscal Conditions in 2002 NOTES 28