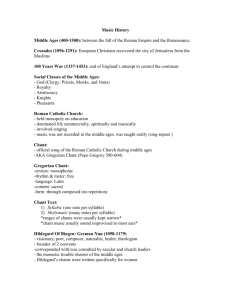

THE GRADUALE ROMANUM: A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH TO CHANT RESTORATION A THESIS

advertisement