EFFECTS OF THE ELIMINATION OF INDIANA PROPERTY TAX

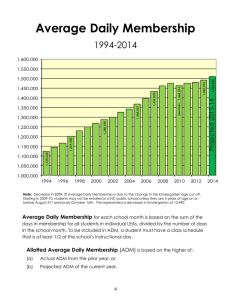

advertisement