Document 10924815

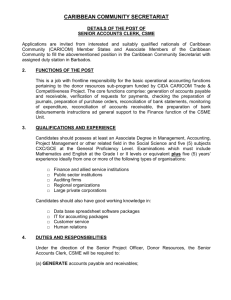

advertisement