Elora Stack REST 392L Civil Rights through Documentary Dr. Mar Peter-Raoul 10/20/09

advertisement

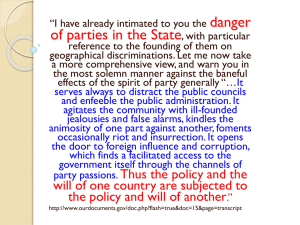

Elora Stack REST 392L Civil Rights through Documentary Dr. Mar Peter-Raoul 10/20/09 Moral Leadership In a New York Times article, “The Invisible War” by Bob Herbert, one leader of morality emerges, Dr. Denis Mukwege, a gynecologist in Bukavu who treats the women of the Democratic Republic of Congo who are brutally raped and mutilated. Dr. Mukwege was born on March 1, 1955, which was about the same year that James Lawson, a leader in the civil rights movement was entering graduate school. At first these two leaders of morality seem not to have any commonalities. One conducts his leadership in Africa, the other in America, both several years apart, and both for different causes, but that is a general assumption, and vastly overlooks the heart of the matter of being a moral leader. Both Dr. Mukwege and Lawson were inspired to help and inclined towards nonviolence at an early age. Dr. Mukwege would accompany his father to his pastoral appointments with patients when he was young. This is where he discovered his desire to help the patients in a more tangible way, by medically attending to their needs. In comparison, Lawson learned non-violence as a young boy, from his mother and his ministering father. Together these men both grew up with the intent of implicating direct action, but not just any direct action, non-violent direct action that would have the people’s best interests at heart. Lawson was born in 1928, so he has a twenty-eight year head start on Dr. Mukwege born in 1955. However, that does not change the fact that they both grew up to be very influential people in society. Lawson, just a freshman in college became a part of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Both organizations were dedicated to the practice of nonviolent resistance to racism. Lawson was later moved to the Nashville chapter of FOR where he taught many workshops on nonviolence to stop segregation. Dr. Mukwege not only practiced medicine that would benefit the poor and war-torn areas of the DR Congo, but he too taught the staff what he had learned studying gynecology at the CHU of Angers in France. Both Lawson and Mukwege trained the people around them furthering their efforts, and by doing so their cause was more effective. Among Lawson's students were people like Diane Nash, John Lewis, and James Bevel, who would later become important figures in the civil rights movement. Dr. Mukwege’s support staff are also important heroes in the fight for proper healthcare for the women, the savagely abused victims of gang-rape. In a New York Times article, Bob Herbert states, “The victims number in the hundreds of thousands. But the world, for the most part, has remained indifferent to their suffering” (Herbert 1). The world may have, but not Dr. Mukwege. He has treated over twenty-one thousand patients in the duration of the DR Congo’s twelve-year war, working eighteen-hour days, with as many as ten surgeries in a day. This is also relative to the work of Lawson, who participated in the many sit-ins, demonstrations, and marches throughout the movement, never giving up, never stopping his non-violent practices despite the daily frustrations of living in a world that had been indifferent to the suffering of African-Americans for so long. Neither has wavered in his beliefs despite different setbacks. For Lawson it was his sentence to federal prison for not registering for the military draft in 1951, based on his moral and religious objections to the war. After prison, Lawson deepened his beliefs of nonviolence by studying the work of Gandhi in Nagpur, India. He returned in 1955, entered graduate school, and went on to work with Martin Luther King, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) where he was involved in some of the most noted sit-ins, demonstrations and achievements of the movement. For Dr. Mukwege it was the destruction of the Hospital of Lemera during the Congo civil war in 1996. As a survivor he pressed on, moving to Bukavu, where he saw the continuing suffering of women during childbirth, and of victims of sexual violence, and established the Panzi Hospital of Bukavu. “Despite the presence in the region of the largest U.N. peacekeeping mission in the world, no one has been able to stop the systematic rape of the Congolese women” (Herbert 1). The same sentiment was held in the struggle for civil rights for African Americans in the years from 1955-1968. The civil rights movement, with its many victims and martyrs seemed to be nearing no end, but after many years progress finally came. In situations of neglect, atrocities, and struggle, there are always the leaders, whether noticed or not, that continue to do what is morally right in the face of adversity. Both Dr. Mukwege and Lawson are important moral figures in the fight for civil rights, whether it is for an entire race, or for a specific gender. The situation in Africa might be equivalent to what happened in America some fifty years back. No hope, neglect for the welfare of the nation’s own people, destruction, lack of media coverage, and a long term battle that would not have an end in sight unless more people stepped up and took the baton of moral leadership, to take necessary steps to help a nation of people recover, and begin to build. People like Dr. Mukwege make the difference between no hope and the possibility of change and peace. Dr. Mukwege although different in background, and born in a different era from Lawson, is of the same caliber of Lawson and the many other heroes of the civil rights movement who made it possible for a race of people to achieve equality. Dr. Mukwege, although only one man unable on his own to stop the atrocities in Africa altogether, is using his abilities and every moment of his life to provide care, and hope to the women and people of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Works Cited: "About: Dr. Denis Mukwege," The Panzi Hospital of Bukavu, 10/19/09. <http://www.panzihospitalbukavu.org/drmukwege.php?weblang=1>. Herbert, Bob, "The Invisible War," The New York Times, 10/19/09. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/21/opinion/21herbert.html?scp=1&sq=Dr.%2 0Denis%20Mukwege&st=cse>. Swomley, John M., "James Lawson, a living civil rights hero," BNET, 10/19/09. <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3861/is_200307/ai_n9295890/?tag=conte nt;col1>.