Document 10913516

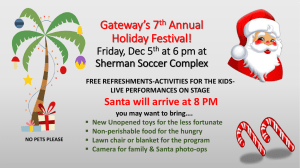

advertisement