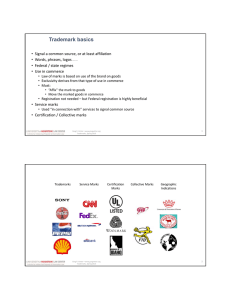

Trademark basics

advertisement