THE BLACK ROCK MARKET SQUARE: A CREATIVE PROJECT

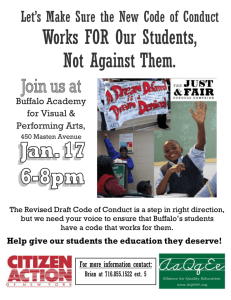

advertisement