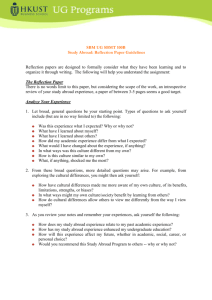

Ball State University Final Approval Sheet for

advertisement