EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT ATTITUDES AND ATTRIBUTIONS OF

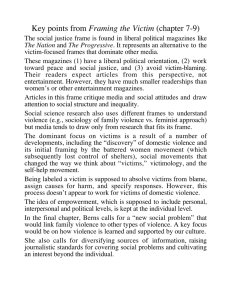

advertisement