ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere thanks and appreciation to some very special people…..my

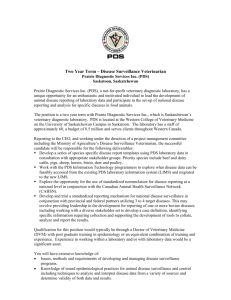

advertisement