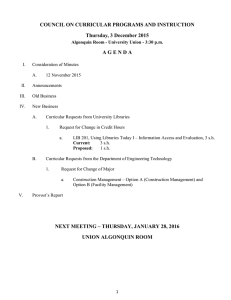

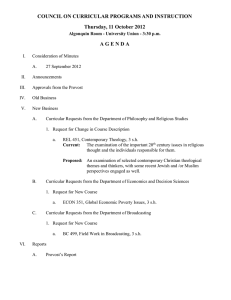

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COMPETITION AND THE CURRICULAR PRACTICES OF

advertisement