Document 10906504

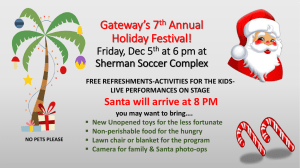

advertisement

Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1--SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, 1968 (50 cents). No. 2—TAOS-RED RIVER-EAGLE NEST, NEW MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE, 1968 (50 cents). No. 3--ROSWELL-CAPITAN-RUIDOSO AND BOTTOMLESS LAKES STATE PARK, NEW MEXICO, 1967 (50 cents.) No. 4--SOUTHERN ZUNI MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO, 1968 (50 cents). No. 5—SILVER CITY-SANTA RITA-HURLEY, NEW MEXICO, 1967 (50 cents). No. 6—TRAIL GUIDE TO THE UPPER PECOS, NEW MEXICO, 1967 ($1.00). No. 7--HIGH PLAINS NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO, RATONCAPULIN MOUNTAIN-CLAYTON, 1967 (50 cents). No. 8—MOSAIC OF NEW MEXICO'S SCENERY, ROCKS, AND HISTORY, 1967 ($1.00). No. 9—ALBUQUERQUE - ITS MOUNTAINS, VALLEY, WATER, AND VOLCANOES, IN PRESS. COVER: Aspen Basin in the autumn two billion years of earth history . . . as seen in half a day CAMEL ROCK SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 1 SANTA FE BY BREWSTER BALDWIN AND FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI 1968 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, PRESIDENT STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, ACTING DIRECTOR THE REGENTS MEMBERS EX OFFICIO The Honorable David F. Cargo .........................Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo ............................. Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS William G. Abbott ..................................................... Hobbs, New Mexico Eugene L. Coulson, M.D..........................................Socorro, New Mexico Thomas M. Cramer ...............................................Carlsbad, New Mexico Steve S. Torres, Jr ....................................................Socorro, New Mexico Richard M. Zimmerly .............................................Socorro, New Mexico First Edition, 1955 Second Edition, 1968 drawings by David Moneypenny photographs by Wayne B. Bera For sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex. 87801—Price $0.50 Preface Santa Fe depends primarily on three reservoirs for its water supply. These reservoirs, which hold almost enough water to satisfy the city's yearly uses, are filled by the springtime melting of the winter's snows. Growth of the state's capital city and several years of drought led to the need to use under-ground water. Wells were drilled for supplementary water on the basis of the technical study of the geology and water resources of the Santa Fe area, later published as U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1525. This pamphlet, which originated the Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past series, stemmed from this technical study of the geology and ground-water resources of the Santa Fe area. It attempted to share the fun of geology with the layman, whether resident or tourist. As the list inside the front cover shows, succeeding efforts established the series. The response of travelers of New Mexico's highways and byways to these little guide books has demonstrated the public's interest in and enjoyment of roadside geology. The current booklet brings the first-edition material up-to-date and incorporates changes in format designed to make it more convenient to use. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Zane Spiegel, then of the U.S. Geological Survey, in preparing the original booklet, Miss Teri Ray for her extensive help with this edition, David Moneypenny for the drawings and sketches, and Wayne B. Bera for the photographs. 1 REGIONAL SETTING 2 Introduction Each highway out of Santa Fe leads to a different landscape. The towering and forested slopes of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, just east of the city, contrast markedly with the deep gorge of White Rock Canyon, some miles to the west. The juniper-dotted plain which stretches to the south and west from Santa Fe gives way on the north to colorful “badlands.” The slow but relentless action of geologic processes, working patiently through the millions of years of geologic time, formed a wide variety of prehistoric scenes in this area. Oceans slowly flooded in and then drained off, leaving featureless coastal plains. Ancient mountain ranges gradually reared their heights, only to be worn down again by ceaseless erosion. And fairly recently in geologic time, perhaps in the last million years, a majestic volcanic mountain subsided in a few fiery months to leave only the remnants we call the Jemez Mountains. We can glimpse some of the scenes of the geologic past by looking at the rocks along the roads near Santa Fe. Although the geologist seldom thinks in terms of number of years, he has accepted estimates of the ages of geologic events, and these will be included as an aid to imagining the geologic history. The laboratory of the geologist is all of the outdoors, and it is well suited for a Sunday outing, for a science-class field trip, or for the sheer fun of hiking over the hills and down the valleys. Four brief trips will reveal chapters in the story of the changing landscapes around Santa Fe. The map in the center of the pamphlet shows the route of each of the four trips and also shows what geologic formation is at the surface in each part of the area. The geologic timetable gives some perspective of the dim past, and the other maps, cross sections, and pictures help to show the shape and nature of the rock units. THE CITY The longest continuously occupied capital and oldest seat of government in the United States, Santa Fe has a full and colorful history. Long before the Spanish arrived, Indians had built pueblos (villages) at several locations in the general area. The junction of mountains, plains, and the Santa Fe River offered protection, food and wood supplies, farm land, and water. In 1598, only 33 years after the founding of St. Augustine, Florida (the nation's oldest city) and 22 years before the Pilgrims touched Plymouth Rock, Don Juan de Oñate established the first colony, San Juan de los Caballeros. The present-day Pueblo of San Juan still proudly bears the name Oñate gave it. In 1610, he moved his headquarters 28 miles southeast where later that same year, Don Pedro de Peralta founded the "Villa de Santa Fe” (Town of the Holy Faith) on the site of an abandoned Indian pueblo. 3 The Spanish maintained a precarious hold on this most northern outpost of their frontier (indeed, on their entire frontier, from western Texas to California). Distance from headquarters and necessary supplies—Mexico City— Durango—Chihuahua, constant political intrigue and strife between representatives of Church and State, and ceaseless raids by Indians made life in the northern province one of isolation, poverty, hardship, warfare, and fear. For 12 years, from 1680 to 1692, the Indians did "rule" New Mexico again, the tribes having united in revolt to drive the Spanish south to El Paso del Norte (Juarez). Don Diego de Vargas reconquered the province and the capital in 1692, ending the Pueblo Revolt and successfully ensuring Spanish domination. With the collapse of the Spanish colonial empire by 1825, the new nation of Mexico assumed sovereignty over New Mexico, as well as the entire Southwest. Unending internal conflict caused Mexico to neglect and almost forget her remote, poverty-stricken, harassed citizens in New Mexico. The opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821 brought the first significant contacts with United States' citizens. Most Americans associate "Santa Fe" with the Santa Fe Trail, which for some 59 of the city's 358 years played a significant role in the life of the city and its appeal to merchants and emigrants from the east. Today, U.S. 85 closely follows the route of the Santa Fe Trail from a few miles above Wagon Mound to its terminus in the Santa Fe Plaza. In some places across New Mexico, one can still see the many ruts that mark the Trail. In 1846, during the war between Mexico and the United States, General Stephen W. Kearny marched his army to the Plaza in August and claimed the territory for the United States. New Mexico and the Southwest came under the jurisdiction of the United States, where they have since remained, except for a short time in 1862 when General Henry Sibley's Confederate troops briefly occupied Santa Fe during the Civil War. Thus, Santa Fe has known Indian, Spanish, Mexican, American, and Confederate rule. The advent of the railroad in 1880 doomed the Santa Fe Trail as a commercial route and started the decline of the city as a rip-snorting trading center. The steep grades proved too severe for the railroads of that day to negotiate and the line had to bypass the capital on its way to Albuquerque. Its main line passes through the station at Lamy, about 17 miles south of the city, where passengers may take the bus into Santa Fe. As you drive about the city and visit its many attractions, see how Santa Fe easily, gracefully, and unmistakably reflects the three major cultures that have affected it Indian, Spanish, and American. The original Spanish PLAZA still serves as the hub of the city and center for municipal activities, from art shows to concerts to dances to religious ceremonies to parades to pageants. You cannot miss the PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS, the long, low building distinguished by the row of wooden pillars that takes up the entire north side of the Plaza. Indians from nearby pueblos offer jewelry, pottery, and other items for sale, under the protection 4 PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS of its wide portal. Built in 1610 and occupied continuously by governors of New Mexico until 1909, the Palace has since housed collections of the Museum of New Mexico and, more recently, exhibits of the New Mexico Historical Society and the School of American Research. On the northwest corner of the Plaza, across from the Palace of the Governors, stands the NEW MEXICO MUSEUM OF (FINE) ART, which emphasizes fine arts of the Southwest. Just off the southeast corner of the Plaza, La Fonda—the Harvey House at the ‘end of the line’—occupies nearly the entire block. Beyond it towers the CATHEDRAL of St. Francis at the head of San Francisco Street. Archbishop John B. Lamy, first non-Spanish priest in the newly created American diocese, built the cathedral in 1869 on the site of a church erected in 1622. He served as the model for "Bishop Latour" in Willa Cather's well-known novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop, and now lies buried, with others, beneath the high altar. Many of the French family names one now comes across in this area belong to descendants of workmen Archbishop Lamy recruited from France to build the cathedral. Low mounds of earth about 1000 yards northeast of the Plaza mark the site of Fort Marcy, constructed in 1846 by General Kearny. SAN MIGUEL MISSION church, south from the Plaza on College Street, dignifies the corner of what looks like a very narrow alley—De Vargas Street. Historians consider the church "early seventeenth century" and the first one in Santa Fe. It contains early paintings on hides and the original 5 SAN MIGUEL MISSION church bell. East of the church, De Vargas Street merges into CANYON ROAD, an old Indian "highway" and for more than a quarter of a century the heart of Santa Fe's famous art colony. Nine INDIAN PUEBLOS lie within easy driving range of the capital and include San Juan, where the Spanish established the first colony in New Mexico; San Ildefonso, home of Maria Martinez, internationally famous potter; and Taos, the state's only occupied multistoried pueblo. 6 Trip 1 TESUQUE FORMATION - SANTA FE GROUP Landmarks—Camel Rock--Bishop's Lodge To Circle Drive, 3 miles north of the Plaza to locate the principal landmarks. Then north to Camel Rock and return through Tesuque and past Bishop's Lodge. Round trip distance, 25.5 miles; driving time 45 minutes. 0.0 Leave Plaza from northeast corner. Drive four blocks north on Washington Street. 0.3 0.3 TURN LEFT at the oval around the Federal Building on the north side for one block to west. 0.1 0.4 TURN RIGHT onto old U.S. 285-84-64, drive north up hill. As you ascend hill, the left road-cuts are in pink-tan silt, sand, and gravel of the TESUQUE FORMATION of the SANTA FE GROUP —geologic terms that indicate divisions of rock units within broad age groups. Ancient streams deposited these sediments in late Tertiary time (see geologic timetable, p. 16). 1.8 2.2 Junction with new U.S. 285-84-64 bypass on left; BEAR RIGHT. 0.3 2.5 Roadcut on left; local erosional unconformity in the Tesuque Formation, formed when streams eroded briefly during deposition of the formation. 7 LOCAL EROSIONAL UNCONFORMITY IN TESUQUE FORMATION 0.2 2.7 BEAR RIGHT onto black-topped road (for short distance) of Circle Drive. 0.9 3.6 STOP A at metal gate on right. The panoramic sketch will identify the mountains visible from this point. Notice lovely expensive homes nearby. To the east are the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. To the southwest in the far distance are the Sandia Mountains just east of Albuquerque. The higher parts of this range consist of the same ancient rocks that make up the Sangre de Cristos. Halfway to the Sandias are the Cerrillos ("little hills"), to the left of which are the Ortiz Mountains. The Ortiz Mountains and the Cerrillos are part of a north-trending chain of moderately young igneous rocks (rocks formed from the cooling of molten rock). In this igneous chain of hills are deposits of zinc, lead, silver, copper, gold, and turquoise. The turquoise was mined by the Pueblo Indians centuries before the Spaniards arrived. It was PANORAMA FROM CIRCLE DRIVE 8 a famous product of Spanish New Mexico and is a trademark of the "Land of Enchantment" today. Turning toward the north you see the "badlands" of the Española Valley, where soft pinkish-tan sandstone is almost the only rock visible. This soft rock is readily weathered into bizarre shapes, such as "Camel Rock," 13.7 miles north of the Plaza on the west side of the highway. You may find fossil bones in these pinkish beds, because famous collections of late Tertiary fossil mammals have been assembled from these beds around Española. To the northwest, forming the high, even skyline, are the Jemez Mountains. Los Alamos is on the plateau sloping toward you, and Bandelier Monument is in one of the many deep canyons that gash the plateau. The canyons drain into the deep gorge of White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande, but the canyon can't be seen until one gets on the very rim. As a matter of fact, there are only a few roads giving a glimpse of the canyon, that to Buckman and N. Mex. 4 to Bandelier National Monument being the easiest to drive. The sand and gravel hills a couple of miles to the west hide most of the lava mesa (Mesa Negra) between White Rock Canyon and the Santa Fe area. However, Tetilla Peak, the most prominent pointed hill on the lava mesa, is visible. On a clear day, the volcanic pile of Mt. Taylor appears in the saddle between Tetilla Peak on the left and the Jemez Mountains on the right; Mt. Taylor is 100 miles west-southwest of here. We have been looking at parts of the Rio Grande trough, which forms an irregular belt 20 to 50 miles wide and trends southward from Colorado toward the south part of New Mexico. The Rio Grande Valley lies in this structural trough. The old rocks are deep below the surface in its center, but they form the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the Sandia Mountains, and other ranges on its borders. The rocks in the trough include not only thousands of feet of sand and gravel brought in by rapidly flowing streams, but also large amounts of moderately young volcanic material. But to have the old rocks forming mountains and the young rocks underlying the lower elevations—that is upside down! In the Great Plains, and on the Colorado Plateau along the Grand Canyon, we see older rocks below and younger above. This is the normal sequence. But along the Rio Grande trough the younger beds were in the wide SHAPE OF THE RIO GRANDE TROUGH 9 4.2 4.4 4.6 4.8 5.5 10 belt that dropped down while its borders rose into mountain ranges. The amount of vertical movement may have been as much as five miles in places. Near Los Lunas an oil test drilled through 9000 feet of basinfilling sand and gravel, although another 5000 feet of the same material had apparently already eroded away. The up-and-down movement was not simple, for it has left a jumble of fault blocks, each one displaced vertically a few hundred or thou-sand feet from the next. This mountain-building caused many earthquakes, but it must have taken several million years if the rate was similar to the mountain-building in California today. 0.6 STOP B at turnout on the left in front of house, at the south end of the ridge overlooking Santa Fe and the Bishop's Lodge highway. From here we can see more of the details of the Santa Fe area proper. The center map shows the distribution of the main rock units, and the geologic timetable lists the sequence of units and geologic ages. Along the east edge of the area are the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, which are here composed of Precambrian and Pennsylvanian rocks. In the southwest corner of the area are many small hills which lie just north of the Cerrillos and which, like the Cerrillos, are made of midTertiary volcanic rocks. The juniper-dotted plain that slopes westward from the mountains across most of the area is underlain by the youngest beds of the "Santa Fe Group." This Group consists of soft sandstone, sand, silt, and gravel of late Tertiary and perhaps Quaternary age. The pinkish-tan soft sandstone and gravel we see along Trip 1 belong to the Tesuque Formation of the Santa Fe. Along the north edge of the area, this plain is being cut up into the "badland" topography that is typical of the Tesuque Formation outcrops farther north around Española. To the west is the lava-capped mesa, Mesa Negra, which projects eastward to the west edge of our area. 0.2 Junction with N. Mex. 22; TURN RIGHT toward Santa Fe. 0.2 Junction with Camino Encantado; TURN RIGHT toward good view westward of Jemez Mountains on western skyline. 0.2 Roadcuts on both sides of Camino Encantado of Tesuque Formation gravelly sandstones unconformable on pink clayey silts. 0.7 Junction with U.S. 285-84-64; TURN RIGHT toward Camel Rock region. As highway descends hill, on right are many roadcuts in Tesuque Formation. SCOTTISH RITE CATHEDRAL 1.1 At sign "Tesuque Turn Off 1000 feet" and junction with dirt road from right, notice flat-topped ridge straight ahead on right side of highway. This gravel-capped hill is a remnant of an ancient higher level of the streams in this area. 2.1 8.7 SANTA FE OPERA turnoff, left. Founded in 1957 by its general director, John Crosby, the Santa Fe Opera Association rebuilt and expanded its facilities following a disastrous fire in 1967. The new design incorporated a fifty per cent increase, both in area and volume, over the original theater, although the sweep and height of its canopy give the same openair feeling. The audience can still view the lights of Los Alamos, thirty miles distant, through an opening at the back of the stage. Internationally renowned, the Opera has presented more than forty-five operatic works (including at least nine American and two world premieres), most of them in English though a sprinkling retains the German, French, Italian, and Russian lyrics. An apprentice program provides singers for the chorus and minor roles. Some operatic 6.6 11 headliners have appeared at this "opera under the stars"; many others who made their debuts here have since attained worldwide recognition. Its season usually runs from mid-June or the first week of July through August. Straight ahead on skyline, the even surface sloping gently westward is the remnant of an ancient, high-level stream bottom. 0.9 9.6 Highway crosses Rio Tesuque. 2.4 12.0 JUNCTION, left, road to Tesuque Pueblo. Always a small village, Tesuque (from Spanish approximation of Indian term for "spotted dry place" because the Rio Tesuque disappears in the sand and comes to the surface only in some spots) holds a major place in New Mexico history. Here occurred the murder that heralded the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and prompted the Indian leaders to change the date of the uprising from August 13 to August 10. Primarily farmers, the Tesuque Indians do not have good-quality handicrafts, but they present colorful and authentic ceremonials and have retained, much of their early culture. 1.7 13.7 CAMEL ROCK. Turn left across the highway into the parking area. Weathering of the soft sandstone of the Tesuque Formation shaped this camel-like rock and the other bizarre forms that characterize the Española Valley. Fossil bones may occur in these pinkish beds, for OUTCROPS OF TESUQUE FORMATION EAST OF CAMEL ROCK 12 BISHOPS LODGE IN FOOTHILLS famous collections of fossil mammals have come from those around Española ("new Spain"; "Spanish lady"). Before you leave the parking area, notice the hills of this interesting formation across the highway from Camel Rock; paying particular attention to the slightly tilted layering effect in the middle sections and the typical badland ruggedness caused by erosion in the area to your right. Also toward the right, notice the white "streak" across a spur of the rough, eroded rocks, as well as directly across the highway: beds of pumicite. They were blown out of a distant volcano and interbedded with the Tesuque Formation's stream deposits. These hills mark the southern edge of the badland topography around Pojoaque (possibly "drink water place" or "place where the flowers grow along the stream") and Española. TURN AROUND; take U.S. 285-64-84 back toward Santa Fe. 3.7 17.4 Junction; TURN LEFT onto N. Mex. 22 to Tesuque village. Do not confuse this place with the Indian pueblo. The route parallels the Rio Tesuque part way. This lovely valley offers many picturesque scenes for your camera of small farms and casas against the mountain back-drop. 0.8 18.2 On northern edge of Tesuque suburbs, highway is on ancient stream bottom 15 to 20 feet above present stream bed; this is a "terrace" whose sands and gravels were laid down 2200 to 1200 years ago; then a lower, deeper stream valley was cut until about 1880 when the present stream channel and its flood plain were formed. The lower terrace, 8 to 10 13 feet above the present stream bed, is to the right of the highway, below the 10-foot bench scarp. It was Rio Tesuque's stream bottom level during the period from 1200 to 1880. 1.0 19.2 Junction (beyond El Nido nightclub); take LEFT FORK, Bishop's Lodge Road. 3.0 22.2 Bishop's Lodge turnoff to left. Clear, swift, cold stream running through the Lodge's grounds is Little Tesuque Creek; it will be seen upstream on Trip 2. 0.2 22.4 To left, you can see the roadcut made by the old highway across the middle of the knoll; ahead in right roadcut are same light-gray tuffaceous sandstones of the Bishop's Lodge Member of the Tesuque Formation. Cobbles of volcanic rocks are scattered through this gray bed, suggesting volcanic eruptions during its formation. 0.6 23.0 In right roadcut is weathered dark-green olivine basalt. This volcanic flow rock also crops out in deep gully left of the highway; again, it tells of the volcanic activity during the late Tertiary when the lower part of the Tesuque Formation was being deposited. 0.5 23.5 Junction from right of Circle Drive. Good view straight ahead of Ortiz and Sandia mountains on southern skyline. OLD ROADCUT IN LIGHT-GRAY TUFFACEOUS SANDSTONES 14 GOVERNOR'S MANSION 0.9 24.4 Mansion Drive intersection. Side trip to right to top of hill gives view of GOVERNOR'S MANSION. 0.7 25.1 Federal Building on right; keep straight ahead. 0.4 25.5 Plaza; end of Trip 1. 15 GEOLOGIC TIMETABLE 16 Trip 2 PRECAMBRIAN AND PENNSYLVANIAN ROCKS Hyde Memorial Park Road Up the Hyde Park Road to Little Tesuque Creek, 5 miles northeast of the Plaza to see Precambrian and Pennsylvanian rocks, then up to Hyde Memorial State Park and the ski basin road. Round trip distance, 17.5 miles; driving time, 45 minutes. The rocks that make up the Sangre de Cristo Mountains just east of the city, and indeed in the eastern part of the city, are largely Precambrian in age. North of the Santa Fe River, Pennsylvanian sediments form sheets that rest on the Precambrian rocks. The word "Precambrian" is quite significant, for it refers to the oldest rocks of the earth. Precambrian rocks represent our record of the first three quarters of geologic time, and yet they are lumped under one term. They are older than rocks of the Cambrian, which is the first period of geologic time during which fossils record an abundance of life. The fossils help to show the relationships between rocks of different areas and also to interpret the origin of these rocks. And so the absence of fossils in Precambrian rocks makes it difficult to understand them. The Precambrian rocks near Santa Fe include pink, green, and gray rocks, with many mineral crystals and usually with a banded or a streaked appearance. These rocks can be seen in several places near Santa Fe. They are well exposed in roadcuts along U.S. 85 between 5 and 10 miles southeast of the city on the Las Vegas highway. We shall see Precambrian rocks on Trip 2, which takes us northeast of Santa Fe on the Hyde Park Road. 0.0 Leave northeast corner of Plaza, jogging northward onto Washington Street. 0.3 0.3 Federal Building on left; keep straight, past Scottish Rite Cathedral. 17 GRAVELS OVER LIGHT-GRAY SANDS NEAR JUNCTION OF N. MEX. 475 AND GONZALES ROAD 0.2 0.5 TURN RIGHT onto Artist Road (N. Mex. 475) at signs for ski area and Hyde Park. 1.5 2.0 Junction with Gonzales Road from right; sign on right "Santa Fe Ski Basin, 15 miles." In left roadcut, the light-gray tuffaceous sands of the Bishop's Lodge Member of the Tesuque Formation are overlain conformably by coarse gravels washed from the mountains during more recent time. For the next two miles, roadcuts are of Precambrian rocks: pink granite, faintly banded, called granite gneiss (composed of pink feldspar and glassy quartz) intruding green schist (thinly banded rock). 1.8 3.8 Side road to right to Hyde Park Estates. Twisted and contorted pink Precambrian granite gneiss in roadcut to left. 0.3 4.1 Rancho Elisa on left. Beds of Pennsylvanian rocks ahead in roadcuts on right. 0.5 4.6 Fossiliferous Pennsylvanian limestones interbedded with shales in right roadcut. Roadcuts ahead in thick limestone; then abruptly along a vertical contact, crumbly Precambrian rocks to the north. The Penn- 18 sylvanian sedimentary rocks are in contact with the weathered Precambrian along a break in the earth's crust, a geologic "fault." 0.7 5.3 STOP C. Turnout on right after crossing culvert over Little Tesuque Creek. Across the road and on the north bank of the creek about 200 feet to the west is a huge vertical wall-like mass of rock. It is worth walking over to see, for it consists of angular pieces of granite glued together by a very fine-grained granite "powder." This "breccia" (broken rock) represents massive granite that was shattered and re-cemented along a fault (slipping of rocks along a break). Many such masses of granite breccia can be found east and southeast of Santa Fe. GRANITE BRECCIA AT STOP C 19 6.3 8.3 8.5 11.8 12.2 20 A few feet to the right of the breccia there is a prospect tunnel. The coarse pink granite on the right intruded the gray banded schist. This is the same relationship we noted three miles back along the road. The thinly banded schists may have been originally sand or mud, or they may represent volcanic rocks; in any case they have been so altered in form (metamorphosed, changed) by heat and pressure, and by the heat and chemical attack of granite intrusions, that there is little hint of their original nature. Up the road from the parking turnout, in the left roadcut, the coarsegrained pink granite that has intruded the gray banded schist forms both sills (intrusions that run parallel to the bedding or banding of the "host" rock) and dikes (tabular masses of intruded rock that cut across bedding). The massive dark-green rock is amphibolite, being made up mainly of green laths of the amphibolite mineral, hornblende. 1.0 Pavement ends; as road climbs into the mountains notice the change in trees from piñon to ponderosa pine, then aspen, and in the highest timber zone, spruce and fir. The white-barked aspen begins in the valleys at Black Canyon camp ground. Precambrian rocks in all roadcuts. 2.0 Enter Hyde Memorial State Park. Camping and picnic tables. 0.2 Parking on right for lodge and store of Hyde Park. TURN AROUND. (Or if you wish to drive it, the road continues nine miles up to the ski basin and Ski Lodge with numerous beautiful mountain views, especially of the aspen basin in the autumn. Roadcuts and outcrops are of Precambrian rocks.) 3.3 Cross culvert over Little Tesuque Creek near Stop C. As road ascends hill, notice that the Precambrian granite gneiss (a gneiss is a coarsely banded rock) is badly shattered and deeply weathered to a rotted mass of half rock and half soil—it is a fossil soil near the top of the hill that formed before the Pennsylvanian sediments were laid down, some 300 million years ago. 0.4 STOP D. Pull off on narrow right shoulder of road just beyond right-angle curve. In roadcut on left, thick-bedded Pennsylvanian limestones abut against the crumbly, rotten Precambrian granite gneiss; their contact is a vertical plane, a FAULT. The massive limestones on the right, south side, of the fault are normally much higher than the Precambrian granite gneiss; thus they have been dropped to their present position. If you climb up onto the hilltop above the roadcut, LA BAJADA HILL AREA you can find the basal Pennsylvanian sandstone and shale unconformable on the Precambrian, resting on the fossil soils derived from the granite gneiss. 0.2 12.4 STOP E. Pull off on narrow right shoulder or at turnoff near culvert on left side of road. Reddish shale and limestone downhill are in basal part of Pennsylvanian beds and are not far vertically above the hidden Precambrian granite gneiss. Eastward along the highway, the Pennsylvanian sedimentary rocks are mostly brown sandstone and shale. Fossils! The limestone ledges here have many fossils. The series of ¼inch discs with hollow centers are parts of crinoid stems. These stems were the attachment of a cup-shaped marine animal; such "sea lilies" inhabit some oceans today. The nut-shaped shells with ridges are brachiopods of several kinds. These and other kinds of fossils have weathered out of the rock and can be found in the loose debris just below the limestone ledges. Weathering is now etching other fossils into relief on the limestone ledges. The abundance of 21 FOSSILIFEROUS LIMESTONES AT STOP E 13.0 15.0 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 22 shell fragments in the rock suggests that the limestone represents a sand of shell particles that accumulated in a surf zone near the shore. 0.6 Entrance to Hyde Park Estates on left. Road is back into Precambrian rocks; roadcuts of pink granite that intruded and "digested" the green schist. 2.0 Junction with Gonzales Road, paved; BEAR LEFT. 1.0 On left, pinkish Tesuque Formation faulted down against Pennsylvanian limestone and shale. 0.1 Pennsylvanian sandstone, coal, shale, and lime-stone in quaries on right. 0.1 Road crosses contact with Precambrian rocks on left and Pennsylvanian on right. 0.1 TURN RIGHT onto Cerro Gordo Road, which parallels the north side of the Santa Fe River and westward merges with Palace Avenue. 1.2 17.5 Northeast corner of PLAZA. End of Trip 2. On the Hyde Park trip, we saw Pennsylvanian sedimentary rocks resting on Precambrian metamorphic rocks. The marine fossils indicate that a sea was there, and some of the sandstone and coal beds were formed by streams and in swamps on land. The shoreline of a Pennsylvanian sea must have moved back and forth across this area. Regional studies suggest that not many miles to the northwest there was a mountain range at the same time, projecting southward from what is now Colorado. But where are the rocks of the Cambrian to Mississippian periods? Most of these are not found until we go to central and southern New Mexico around Socorro and Truth or Consequences. Indeed, the area in which Pennsylvanian beds rest chiefly on Precambrian rocks includes much of northern New Mexico as well as parts of southern Colorado and northwest Arizona. There are some remnant patches of Mississippian limestone and sandstone between the Pennsylvanian and the Precambrian—a small block along Little Tesuque Creek between the Hyde Park Road and Bishop's Lodge, many remnants along the Pecos valley to the east, and others—but we infer that for the most part there was a landmass that was being eroded for much of the long period from Cambrian to Mississippian time. Some sediments, such as the Mississippian limestone and sandstone, were deposited during this period but were eroded in most areas before the Pennsylvanian. PERMIAN THROUGH CRETACEOUS ROCKS After the Pennsylvanian Period, there is another long gap in the geologic record near Santa Fe. No rocks near the city represent the Permian, Triassic, Jurassic, or Cretaceous periods. However, rocks of these ages are exposed along Galisteo Creek near Cerrillos. Permian and Triassic sedimentary beds can be seen around Canyoncito, 13 miles southeast of Santa Fe on U.S. 85, and Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous rocks are well exposed on the north side of Galisteo Creek, 2 to 5 miles east of U.S. 85, 22 miles southwest of Santa Fe along La Bajada Hill. These rocks were deposited in the Santa Fe area but have been buried by younger beds or removed by erosion. The Permian through Cretaceous sediments represent a fluctuation of marine and nonmarine conditions. The coal at Madrid to the south is Late Cretaceous in age and formed on the coastal plain of the last large sea to invade north-central New Mexico. 23 Trip 3 EOCENE - OLIGOCENE - MIOCENE "Garden of the Gods," Cerrillos, Turquoise Hill, La Bajada Hill, and Cienega GALISTEO FORMATION Late in the Cretaceous Period, the flat coastal plain gave way to rising mountains. This mountain chain was a forerunner of the present Rocky Mountains. Later geologic events have obscured the exact limits of the Eocene mountainous areas around Santa Fe. But there was a basin where Lamy, Galisteo, and Madrid are now. Streams that headed in these highlands carried sand, mud, and gravel into the basin to make up what we call the "Galisteo Formation." To "Garden of the Gods," Cerrillos, Turquoise Hill, La Bajada Hill, and Cienega southwest of Santa Fe—to see Eocene to Miocene sediments and volcanic rocks. Round trip distance, 72 miles; driving time, 2 hours. 0.0 Leave Plaza; go southwest to join Cerrillos Road (U.S. 85) south toward Albuquerque. 1.3 1.3 Junction with St. Francis Drive at Traffic light; continue straight ahead on Cerrillos Road. 1.8 3.1 Traffic light at junction with Osage Avenue, U.S. 85 bypass. 1.2 4.3 Notice bluff on the north side of Santa Fe River, to the right; a similar rise in ground is on the left to the south. We are driving along the floor of an earlier, higher valley of the Santa Fe River. 26 LOOKING SOUTH TOWARD VERTICAL PALISADES OF GALISTEO FORMATION AND GALISTEO VALLEY WITH ORTIZ AND SANDIA MOUNTAINS ON SKYLINE 6.2 8.7 9.8 1.9 Junction to municipal airport; KEEP LEFT on U.S. 85. 2.5 Pumice (white frothy particles blown out of a volcano) in roadcuts. 1.1 Junction, TURN LEFT onto N. Mex. 10. 2.4 11.2 New Penitentiary on right (west). 5.0 17.2 Continue straight ahead; junction with N. Mex. 22 from right. It leads west to Picture Rock. 3.8 21.0 Vertical palisades of sandstone on right. 0.2 21.2 STOP F at turnout near Broken Hill Ranch. The vertical beds of red mudstone and yellow sandstone, which make a miniature "Garden of the Gods," are part of the Galisteo Formation. Geologic formations are named for geographic features; this unit was named for Galisteo Creek, which lies just to the south between here and the Ortiz Mountains. Two kinds of fossils have been found in the formation not many miles from here, petrified wood and mammal bones. The wood, mostly 27 pine, is abundant at Sweet's ranch, a mile southeast of Broken Hill Ranch. The bones have been identified as late Eocene titanotheres. The titanothere is extinct, but, according to the people who like to put old bones together, it resembled a moronic rhinoceros. From the fossils and other characteristics of the Galisteo Formation, it is evident that the sand and mud were carried into a basin by streams in a climate more humid than today's climate. Some of the streams must have flowed rapidly in flood-time to carry the boulders and pebbles visible in some of the beds. If sediments such as these sandstones and mudstones are deposited as horizontal sheets, why are the beds standing on end? In this area, the beds were tilted to their present vertical position by a mass of hot, pasty rock that forced its way upward from a mile or more below the surface. Several such igneous intrusions make up the Cerrillos, a few miles to the west. 1.4 22.6 Roadcuts of reddish Galisteo Formation beds. "GARDEN OF THE GODS" STEEPLY DIPPING BEDS OF GALISTEO FORMATION AT BROKEN HILL RANCH 28 0.5 23.1 Roadcuts in vertical, contorted black shale and tan sandstone of the Cretaceous Mesaverde Formation. These marine beds are some of the youngest Cretaceous rocks in the region. 0.8 23.9 Ridge to right of highway capped by massive monzonite rocks intruding black Mancos Shale. The marine Mancos Shale is one of the older of the Cretaceous units in this area. 0.3 24.2 Junction with road to Cerrillos; TURN AROUND. N. Mex. 10 continues south across Galisteo Creek to Madrid. To the north on the other side of the A. T. and S. F. Railway tracks, and on the north side of the valley, the black Mancos Shales are capped by high-level stream gravel and intruded by the monzonite sills at the east end of the shale cliff. 1.1 25.3 Roadcuts again in vertical Mesaverde Formation beds. To left in distance, to northeast, horizontal beds of the Santa Fe Group are unconformable on steeply dipping Cretaceous and Galisteo layers. 1.9 27.2 Garden of the Gods, again. VERTICAL MESAVERDE FORMATION SHALE AND SANDSTONE 29 PICTURE ROCK 0.3 27.5 In left roadcut, Santa Fe Group pink sands unconformable on yellowish Galisteo beds. 0.8 28.3 Side road, right, to village of Galisteo. 1.5 29.8 Cross Arroyo Coyote; notice the water from Coyote Spring here and also the volcanic rocks in the stream bed. 1.4 31.2 Junction with N. Mex. 22; TURN LEFT. 0.8 32.0 "Picture Rock," a butte of igneous rock on left. The Cerrillos, straight ahead, and the other knobs and hills around here are of similar kinds of rock. 0.6 32.6 Highway makes right-angle curve to right. 1.0 33.6 Right-angle curve to left. 0.3 33.9 STOP G. The many prospects and mine workings on Turquoise Hill, to the north, date back at least to the turn of the century, and pos- 30 sibly centuries earlier. Perhaps $2,000,000 worth of turquoise was won from Turquoise Hill. Another famous turquoise mine, Mt. Chalchihuitl, is in the middle of the Cerrillos and was worked by the Indians before the Spanish arrived. Hike the 1000 yards to the north to see the old workings. VOLCANOES Deposition of the mud and sand of the Galisteo Formation was ended when volcanic outpourings blocked and choked the streams. Lava, ash, and bouldery flows covered much of the surface west of Santa Fe. There was a north-south belt of volcanic centers that included the Ortiz Mountains, the Cerrillos, and the Cienega area. The purplish-gray rocks seen back in Arroyo Coyote are volcanic rocks; the grayish intrusive rocks of Picture Rock and Turquoise Hill are monzonites related to the volcanic rocks. These are called the Espinaso volcanics. 1.0 34.9 Right turn; Cerrillos to west; base-metal mines (lead and zinc) have produced some ore from the Cerrillos in the past. 0.4 35.3 Continue straight ahead; side road from left from Cerrillos; good view to north. VIEW NORTHWEST FROM CERRO DE LA CRUZ ACROSS THE CIENEGA AREA TOWARD THE JEMEZ MOUNTAINS. U.S. 85 IN LOWER PART OF PICTURE 31 ROADCUT AT 43.6. MORRISON ON LEFT FAULTED AGAINST MANGOS AT EXTREME RIGHT OF PHOTOGRAPH 1.7 37.0 Bridge across Alamo Creek. Water again in this lush, grassy valley. Bonanza Hill is ahead to right; Cerro de la Cruz is the black cone-shaped butte ahead to left. The mound just to our right in the valley was the site of a mill that treated the lead-zinc ore from the Cerrillos in the 1880's. There is no trace now of the mining camp of Bonanza, which was on the hill just behind us. 0.2 37.2 Curve to left. 0.9 38.1 Junction with U.S. 85 at Turquoise Trading Post. TURN LEFT onto U.S. 85, drive southwest toward La Bajada Hill and Albuquerque. Sandia Mountains on southwest skyline; La Tetilla Peak to northwest with Jemez Mountains on northwest skyline. 0.6 38.7 Bridge over Alamo Creek; note swampy stream bed. 1.1 39.8 Low ledges of black basalt to right beyond fence. These basalt flows were extruded from the basalt volcano ahead on the right. 1.1 40.9 Crest of hill on curve to right; basalt volcano cone to right. 1.8 42.7 Begin descent of La Bajada Hill. Calichified (rich in lime) gravels and soil on top of black basalt flows at top of hill. Basalt is vesicular (full of holes from ancient gas bubbles) and flow banded. In left roadcut below the basalt are pinkish silts and clays of the Santa Fe Group, partly baked when the hot basaltic lava flowed over them. 32 CHANNEL-FILLING SANDSTONE IN GALISTEO FORMATION 0.2 42.9 In left roadcut, greenish-gray to gray-black Cretaceous Mancos Shale cut by vertical dark-gray dike of intrusive rock called "limburgite." Pinkish Santa Fe Group beds above the Mancos. 0.7 43.6 In left roadcut, the yellow-brown sandstones and gray shales, cut by the reddish-purple, nearly vertical igneous dike, are beds of the Morrison Formation. These rocks are older than the Cretaceous Mancos Shale, being of Jurassic age, about 145 million years old. They were deposited on vast flood plains and in and near meandering streams. To the north near Rosario, they overlie the Todilto gypsum, another Jurassic rock unit. At the west end of the left roadcut, the yellowish Morrison sandstones are in vertical contact with blackish-gray Mancos Shale—another geologic fault that broke the rocks, the Mancos Shale on the west being down-dropped along the fault against the older (therefore lower in the rock sequence) Morrison beds. In the broad valley to the north on the right side of the highway, reddish beds of the Galisteo Formation crop out; these are on the west side of another fault along which they were dropped down to the level of the Mancos Shale. Most of the La Bajada escarpment is a series of complex faults, with the down-dropped blocks on the west side—this is how the land surface has been affected by the geologic structure to show the change in rock elevation from the basalt-capped Santa Fe plateau down to the Rio Grande Valley. 0.2 43.8 High roadcut on right is of the greenish-gray Espinaso volcanic rocks, here mostly conglomerates with the cobbles of volcanic materials. The 33 GALISTEO FORMATION OUTCROPS ON LA BAJADA HILL lenticular beds dip to the northeast; thus another fault has been passed since the previous roadcut, with the Espinaso units dropped down to the west. The Espinaso beds grade downward into the Galisteo layers in the valley to the west. 0.1 43.9 Roadcuts in reddish sandstone, siltstone, and claystone of Galisteo Formation. The massive, lenslike sandstone in the upper part of the right roadcut is a channel sandstone, deposited near the center of an ancient stream during Eocene–Oligocene time. Typical outcrops of the Galisteo Formation occur in the right roadcut a few hundred feet downhill, near the highway sign; lenticular beds of pebbly sandstone, massive siltstone, and silty, layered shale and claystone, all various hues of reddish brown. 0.8 44.7 Bottom of La Bajada Hill. Outcrops on both sides of highway are of pinkish Santa Fe Group beds, partly covered by local stream wash sands and gravels. Again a large fault has been crossed, between the Galisteo and the Santa Fe rocks, with the Santa Fe layers down-dropped to the west. 0.9 45.6 Crossroad; TURN AROUND, carefully. Road to right to Cochiti Dam on the Rio Grande; left to Kaiser Gypsum Rosario plant and quarry. The Jurassic Todilto gypsum is used to make gypsum wall-board. It was deposited about 150 million years ago in an extensive 34 inland sea that covered most of north-central and northwestern New Mexico. RETRACE U.S. Highway 85 toward Santa Fe. 0.3 45.9 In right roadcut, local stream gravels that are younger than the Santa Fe Group beds they overlie. Ahead are badlands cut in reddish layers of the Galisteo Formation at the base of La Bajada Hill. 0.6 46.5 At bottom of La Bajada Hill, cross fault zone between down-dropped pinkish-brown Santa Fe beds to west and the reddish Galisteo Formation to the east. The whitish streaks in the Galisteo are lenses and nodules of "lime," calcium carbonate and some gypsum. 1.8 48.3 High roadcut on right of greenish-gray Mancos Shale cut by vertical limburgite dike, overlain by pink "baked" Santa Fe bed and capped by the black basalt flow. 2.5 50.8 Turn out on right as descend from crest of hill, near convenient high-way department litter can. View to northeast, across valley of Alamo Creek, of the Santa Fe area. The city, about 15 miles away, lies snuggled at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo ("Blood of Christ") Mountains; when the setting sun strikes them just right, these mountains appear to be a beautiful darkred color. To the right of U.S. 85, a few miles to the west, are the coneshaped hills of Cerro de la Cruz and Bonanza Hill. 1.7 52.5 Bridge across Alamo Creek; cottonwood grove on right fed by spring water. VIEW NORTHEAST FROM MILEAGE 50.8 TOWARD SANTA FE 35 PANORAMIC VIEW TO SOUTHWEST. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, BONANZA HILL, … 0.6 53.1 Junction with N. Mex. 22 from right, south, at Turquoise Trading Post. About half a mile to the northeast, the highway ascends a small rise; just off the highway to the right is a black, cone-shaped, pointed hill, Cerro de la Cruz (hill of the cross). Watch carefully for junction to left with N. Mex. 22. 0.7 53.8 TURN LEFT onto black-topped N. Mex. 22 to Cienega. Cross cattle guard just off U.S. 85 and STOP for views. STOP H. Looking back toward the highway, you can see the following landmark features in a panoramic view from east to west, clockwise in order: Bonanza Hill Turquoise Hill in saddle Cerro de la Cruz Cerrillos (Ortiz Mountains in saddle of Cerrillos) Sandia Mountains highway to Albuquerque volcano just west of highway (source of several lava flows) canyon of Santa Fe River cutting into the lava mesa (Mesa Negra) Tetilla Peak Jemez Mountains on skyline 36 …CERRO DE LA CRUZ, CERRILLOS, SANDIA MOUNTAINS, AND HIGHWAY Cerro Seguro—the rounded black knob this side of the mesa Cerros del Rio—shrub-covered high mesa to northwest and just to the north of us a wet valley—water again "Cienega" means "marsh" or "miry place"—there are many seeps and springs. Grass is green in the valley of Cienega Creek, and irrigation ditches line the sides. Where does this water come from? The arroyos between here and Santa Fe are dry and sandy. The mountains east of Santa Fe are made of fairly impermeable rock, so both rain and melting snow run out onto the plain and seep into the sandy channel fill of the numerous arroyos. Hard summer rains on the plain also soak in fairly quickly. The water seeps slowly westward toward the Rio Grande, for the rock under the plain is sand and gravel. But at Cienega, there are several kinds of volcanic rocks, all practically impermeable. This rock is a barrier to groundwater movement, and so the water comes to the surface. The quiet old community of Cienega has for many years diverted this discharging ground water for irrigation along the narrow valley of Cienega Creek. 0.9 54.7 Abandoned Cienega school on right, as descend into valley of Cienega Creek. Behind and to north is St. Joseph Church. Knob behind school and the one ahead of us are part of a dike (a vertical, crosscutting igneous rock sheet) shown as "d" on the sketch map. 37 VIEW TO NORTHWEST ALONG CIENEGA ROAD. LEFT OF ROAD, JEMEZ MOUNTAINS ON … 0.1 54.8 Bridge across Cienega Creek. 0.1 54.9 STOP I. Pavement ends; dirt road ahead leads left, west, to a local ranch; right, it follows Cienega Creek upstream. The geologic history of the Cienega area has been pieced together by geologists from the many rock outcrops. With the help of the map of the Cienega area, you can drive along each of the roads and see the main features. The vertical relationships are shown on the cross section. The central part of the area consists of monzonite, the gray-brown rock with the small, light-gray feldspar crystals. The monzonite was once a pasty mass of molten rock that forced its way up through other rocks as an igneous intrusion. The Galisteo Formation (the red beds which you saw on the way down from the highway), and some volcanic breccia southwest of the monzonite were tilted by this intrusion. Later the surface was worn down by streams to expose the monzonite. Next, two sets of volcanic breccias and flows of the Espinaso volcanics were poured out onto the surface. These breccias can be seen just east of the dam (marked on the Cienega map). On the southwest side of the dam, there are elongated holes in the rock—these were gas bubbles that were stretched as the lava moved. The cliffs northeast of the dam along the road show the nature of the volcanic breccias 38 …SKYLINE AND TETILLA PEAK; TO RIGHT, CERRO SEGURO AND CERROS DE RIO ON SKYLINE clearly (photograph). Small and large blocks of volcanic rock are embedded in fine-grained volcanic material. These volcanic breccias are common in many parts of New Mexico and represent lava flows or ash flows that picked up blocks of earlier formed rock. The breccias were buried by flows of the Cieneguilla limburgite, a basaltlike black lava that forms cliffs between Cieneguilla and Canyon along the Santa Fe River. The hill with the white mission cross and Cerro Seguro are made of limburgite, as is the cap of Cerro de la Cruz. Cerro de la Cruz is not a complete volcanic cone, but it may be the core or plug of a former volcano. All these volcanic rocks probably were formed in Oligocene–Miocene time. Later faulting has tilted the volcanic breccias and offset some of the strata of rock. A fault can be seen north of the road that leads toward the Gallegos ranch. Here the monzonite is faulted up against red beds of the Galisteo Formation. Before leaving the Cienega area, notice two other kinds of rock, the gravel and the mesa-capping lava, which belong in a later part of the story. The gravel (not shown on the map) underlies the lava west of the Santa Fe River and blankets most of the rest of the Cienega area. However, hills of the volcanic rocks were not all buried under the gravel and lava flows. The monzonite and the limburgite are resistant to erosion and both form knobs that stand above the level of Mesa Negra. 39 MAP AND CROSS SECTION OF ROCK UNITS IN THE CIENEGA AREA b, basalt flows; A, Ancha Formation (not shown on map); C, Cieneguilla limburgite; v, Espinaso volcanics; m, monzonite; G, Galisteo Formation; d, dike (not shown on section); dashed line, boundaries of rock units; faults indicated by D/U (D—down, U—Up). 40 RUGGED CLIFFS OF ESPINASO VOLCANIC BRECCIA ALONG CIENEGA CREEK 54.9 Leave STOP I; TURN RIGHT, eastward and follow the unpaved road as it parallels Cienega Creek through the scenic farming community. 0.7 55.6 Espinaso volcanic rocks, here volcanic breccias, in cliffs on left. 55.9 0.3 Junction, TAKE LEFT FORK. Right fork follows an arroyo for about 2 miles, then crosses the mesa and rejoins U.S. 85 (I-25) about half a mile south of the junction with N. Mex. 10. 2.0 57.9 Cross cattle guard after driving under telephone line on flat mesa. In onefourth mile, begin descent into valley of Santa Fe River. 0.6 58.5 Cieneguilla; small church a quarter of a mile on left; sharp RIGHT TURN at base of the bluff; road then angles across the Santa Fe River flood plain. The channel from Santa Fe downstream to Cieneguilla is a broad sandy arroyo flanked by terraces (former, higher, stream floors). This sandy stream bed, usually dry, is in marked contrast with the running water and narrow canyon of the Cienega area. (But do not risk this "dry" arroyo during or after stormy weather!) 0.4 58.9 Cross to west side of Santa Fe River arroyo. 41 0.6 59.5 Junction, KEEP RIGHT, along side of arroyo. The cinder pit on the hillside to the west was once part of a volcanic cone; it was later buried by a lava flow. 2.3 61.8 Cross to south side of Santa Fe River and drive up onto main terrace. 0.2 62.0 Sewage plant on left. 1.3 63.3 TURN LEFT onto black-topped road from municipal airport. In less than a mile, Santa Fe Municipal Golf Course is on right. 2.7 66.0 Junction with U.S. 85, Cerrillos Road. Follow direction signs and TURN LEFT onto Cerrillos Road toward Santa Fe. 6.0 72.0 Santa Fe PLAZA—altitude 6990 feet. End of Trip 3. CLOSE-UP OP VOLCANIC BRECCIAS 42 Trip 4 MIOCENE TO PLEISTOCENE Buckman Road THE SANTA FE BEDS The rise of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the filling of the Rio Grande trough with sand and gravel and with lava flows are the important last chapter of our story; the final page is recorded in the downcutting of the present streams. Back in 1869, F. V. Hayden made a geologic reconnaissance in the Santa Fe area. He originated the name "Santa Fe" for the beds of sand and gravel, partly consolidated into ledge-forming rocks, that crop out from Galisteo Creek north toward Taos. More recent geologic studies have shown that the Santa Fe beds accumulated as "basin-filling" sediments during the formation of the Rio Grande trough, from Miocene to Pleistocene time. Perhaps the trough is still actively deepening. The movement, which began in the Miocene, has been primarily along faults, or breaks, rather than a result of warping or folding. As the mountains slowly rose and the trough subsided, the streams brought more and more sand and silt and gravel into the basins that make up the trough. Near Los Lunas, southwest of Albuquerque, the basin fill is more than 2 miles thick! In the Santa Fe area, some of the details of this basin filling can be seen. Toward the end of the volcanism that we noted around Cienega, volcanic ash was blown into the air and settled down over a large area. The whitish ash beds around Arroyo Hondo and Bishop's Lodge belong to this stage of Miocene time. At about the same time, the present Sangre de Cristo Mountains began to rise along faults trending north and north-northwest. The long straight valley traversed by U.S. 85, 5 to 10 miles southeast of Santa Fe, was eroded along one of these faults. Streams, invigorated by the steeper slopes, carried sand and silt westward to pile up several thousand feet of basin-fill. If we had been here some 10 or 15 million years ago, about at the end of the Miocene epoch, we would have noticed frequent stream floods carrying debris down from the mountains east of us, but even in a lifetime we would not have been particularly impressed with the accumulation of sediments. If the main amount of basin-fill accumulated in only a million years, a rate of an inch every ten years would result in nearly 10,000 feet of sediment! This thick part of the Santa Fe beds, characterized by ledge-forming soft sandstones exposed north of the city, is called the Tesuque Formation; a typical exposure is shown in the photograph. 43 The Tesuque Formation around Pojoaque and Española has yielded abundant bones and teeth of the horses, deer, camels, bears, and other mammals that lived during the late Miocene and early Pliocene. The nature and abundance of fossils indicated a fairly moist climate and grassy plains, and generally good living conditions. Collections and studies of fossils of these beds have been made since 1880, and the Frick Laboratory of the American Museum of Natural History is making an intensive study of the fossils. At some time in the Pliocene epoch, the Tesuque sediments were in turn broken by faults and tilted westward about 10 degrees. A prominent westwardsloping fault block just north of Pojoaque can be seen from U.S. 285 north of Santa Fe. At the same time, there was a final upfaulting of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The plains west of the mountains were eroded, for the Tesuque Formation is absent both at the "Garden of the Gods" (Stop F) and at Cienega. The gravel at both of these places belongs to the Ancha Formation, the next younger unit of the Santa Fe beds. The erosion in the Pliocene produced a westward-sloping plain, although some of the volcanic rocks around the Cerrillos and Cienega stood as hills above this plain. Eventually the plain was buried under the sand and gravel of what we call the Ancha Formation. The relationships of the Ancha Formation are seen on Trip 4. The westward-sloping surface was covered by cinders from volcanoes, such as the cinder pit north of Cieneguilla, and then was buried under lava flows. The eastern limit of the flows was about the position of the present cliff of basalt along the west edge of the Santa Fe area. Here the lava is only 50 feet thick, but it is several hundred feet thick in White Rock Canyon opposite Frijoles Canyon. A water well on the mesa encountered 1000 feet of basalt, although some of this thickness is probably of an earlier set of flows that form the high, dissected mesa of the Cerros del Rio. VIEW SOUTHEAST TOWARD THE SANGRE DE, CRISTO MOUNTAINS, 10 MILES NORTH OF SANTA FE; TESUQUE FORMATION IN MIDDLEGROUND 44 DIKE WITH UNCONFORMITY With the outpouring of basaltic lava west of the Santa Fe area, the streams that drained westward from the mountains were dammed up. The Santa Fe River was turned southward toward Cienega by the flows. Erosion and deposition were only minor for part of the Pleistocene. Now our story shifts to the Jemez Mountains. Volcanic activity that continued through Ancha time had by now formed a magnificent towering mountain. The mountain may have been capped with snow and ice, and there were glaciers high in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, too. The climax of volcanic activity took place in a few fiery months. Pumice was blown out over a wide area. Shortly afterward, great volumes of hot volcanic ash flowed eastward from the crater. The ash flows filled canyons that had been cut in the basalt—a 500-foot buried canyon can be seen in Frijoles Canyon below the Bandelier Monument—and diverted the ancestral course of the Rio Grande. If you drive up toward Bandelier National Monument on N. Mex. 4, you will see this sequence near the junction of the highway leading to Los Alamos; basalt is overlain by pumice, which in turn is overlain by the tan, cliff-forming ash flows. With the outpouring of the pumice and ash, the mountain peak subsided or collapsed. All that remains is a circular "caldera," and Valle Grande is part 45 of this depression. The rim of the caldera, which measures 16 miles across—one of the largest known in the world—forms the mountains just west of Los Alamos. Fortunately, some of the pumice was blown across the Santa Fe area, and so we can correlate the events around Santa Fe with the volcanic history of the Jemez Mountains. The pumice indicated in the sketch of buried land surfaces is 5 miles south of the Buckman road, but another deposit can be seen along U.S. 85, 8.7 miles southwest of the Plaza. These and other pumice deposits occur in a band trending southeast across the center of the Santa Fe area. Although we cannot give accurate geologic dates for the post-Tesuque events, the basaltic flows are possibly early Pleistocene and the pumice slightly later. Faulting produced the scarp at La Bajada, southwest of Santa Fe, and the waterfall of the diverted Santa Fe River began cutting headward, forming the 400-foot canyon below Cienega. By the time the waterfall had reached Cienega, the river upstream had brought in the volumes of gravel seen around the village. The gravelly floor of the valley of this ancestral river has proved to be fairly resistant to erosion, and so when downcutting of streams in the present cycle began, two streams took over the work. The present Santa Fe River is on the north side and Arroyo de los Chamisos on the south. Other drainage modifications of this recent vintage include the course of the Santa Fe River through narrow canyons in the Cienega area and the headwater diversions of creeks in the mountains. The last trip takes us to the northwest corner of the Santa Fe area, where Cañada Ancha drains northwest at the base of the lava mesa in a youthful course. Buckman Road northwest of the Plaza to see the rocks and buried surfaces of the Santa Fe beds. Round trip, 24 miles; driving time, 45 minutes. 0.0 Leave Plaza on north-west corner at west end of Palace of Governors. Drive west past Art Museum for one block; TURN RIGHT onto Grant Avenue and after a half block, TURN LEFT at traffic light onto Johnson Street. Drive west two blocks. 0.4 0.4 Junction with U.S. 285-8464, Jefferson Street; TURN RIGHT, north onto highway. 46 NEW ME XICO MUSEUM OF ART 0.4 0.8 Rosario Chapel cemetery on right. Legend has it that De Vargas camped here before retaking Santa Fe in 1892 and built a chapel, part of which comprises today's Rosario Chapel. He attributed his victory of reconquest to La Conquistadora, represented by a statuette of the Blessed Virgin that he brought with him. Although normally honored in a side chapel of the Cathedral, the statuette becomes the focus of a religious procession early each summer to return it to the Rosario Chapel for a period of veneration of the Virgin. 0.2 1.0 Santa Fe National Cemetery to right, one of the 97 in the country and analogous to Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Title to the original land was donated by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Santa Fe through Bishop John B. Lamy on July 2, 1870. Initial interments at the site were the remains of United States' soldiers from the Civil War battle of Glorieta. Among others buried here are Governor Charles Bent, General Patrick J. Hurley, and Oliver LaFarge. 0.2 1.2 TURN LEFT off highway. 0.2 1.4 Cross, carefully, North St. Francis Drive onto Alamo Drive. 47 BURIED LAND SURFACES NORTHWEST OF SANTA FE 0.3 1.7 TURN RIGHT onto Camino de las Crucitas; pavement ends in half a block; go up hill on dirt road. Well-exposed outcrops of Tesuque Formation in roadcuts. 0.3 2.0 Junction where Arroyo Torreon crosses; TAKE RIGHT FORK. 0.1 2.1 Junction, TAKE LEFT FORK. 0.6 2.7 Road crosses abandoned railroad grade as it did at Arroyo Torreon; as you climb onto ridge top, notice this railroad grade to the north along north bank of Arroyo de los Frijoles, to right. This railroad once extended up the Rio Grande into Colorado. For the first 6 miles from Santa Fe, the stream and roadcuts show the westward-dipping, soft sandstone and siltstone of the Tesuque Formation. 1.6 4.3 Cross sandy channel of Arroyo de los Frijoles; take LEFT FORK at top of hill on northwest side of valley. 0.5 4.8 Junction, TAKE RIGHT FORK. 1.0 5.8 Cross sandy arroyo. 0.4 6.2 Cross Arroyo Calabazas (where are the pumpkins?). 48 0.3 6.5 Top of hill; TAKE LEFT FORK. Cerros del Rio straight ahead and Jemez Mountains on skyline. 0.9 7.4 Cattle guard. 0.2 7.6 Junction, continue straight ahead on LEFT FORK, cross cattle guard. Ranch road to right. 0.8 8.4 STOP J. Here the road begins to drop off the upland surface. A thin bed of gray-black basalt cinders (tuff) crosses the road here. The cinders forming the tuff bed were spewed from one or several of the volcanoes that dot the lava mesa, and they were deposited in a few weeks—an instant of geologic time. They thus rest on a former land surface. From Stop J eastward for 2 miles, the tuff is on the Tesuque Formation, and from here westward it is on the Ancha Formation, as indicated in the sketch of the buried land surfaces. Careful geologic mapping along the arroyos that are cutting down through the sequence of former land surfaces has shown that the Ancha Formation rests on a westward-sloping surface that cut across the tilted Tesuque Formation, and the cinders preserve a second buried land surface. The upland remnants are all that is left of a third surface now being eroded by streams. 1.7 10.1 Road joins abandoned railroad grade in valley of Alamo Creek. The PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS ON NORTH SIDE OF PLAZA 49 hills nearby are made up of the gravels and sands of the Ancha Formation; about 200 feet of the Ancha underlie the basalt-capped mesa ahead—ten times the thickness of the Ancha Formation at Stop J. 2.0 12.1 Windmill. The road follows the railroad and arroyo (Canada Ancha) north to Buckman, an abandoned community, and joins N. Mex. 4 west of Pojoaque, but it crosses private property. Turn around and return to Santa Fe. End of Trip 4. 50 Conclusion In these brief trips near Santa Fe, we have had glimpses of past landscapes. Moreover, it is now evident that modern landscapes are transient. How old, then, are the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, for example? Well, they are made of Precambrian and Pennsylvanian rocks, and so the rocks are a quarter of a billion to perhaps a billion years old. These rocks were forced up into the mountains about the end of the Cretaceous Period, some 70 million years ago, and though they were then eroded to a low elevation, some vestiges of the "first shaping" remain. The rocks were faulted up to their present heights during "Santa Fe time," beginning perhaps 15 million years ago and continuing almost to the present. Modeling of these heights is fairly recent, going back scarcely before the Pleistocene, and this phase is still going on. In the next 100,000 years, the climate may return to glacial conditions, and in future millions of years, mountain-building may be renewed—or it may be going on today! THE MAP ENDS HERE TOO 51 Some Additional Reading If you wish to learn more about geology, the following books will help: Geology—Merit Badge Series: Boy Scouts of America, 1953. (An excellent introductory booklet on geology.) The Rock Book: C. L. and M. A. Fenton, Doubleday, Doran & Co., Inc., 1940. (About minerals and rocks.) The Rocky Mountains: Wallace W. Atwood, Vanguard Press, 1945. (Geology, scenery, folklore, and landforms of the Rockies.) If you wish to read more about the geology of this region : Tertiary geology of the Galisteo—Tonque area, New Mexico: Charles E. Stearns, Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 1953, vol. 64, p. 459-508. (This is a recent study with a good list of other pertinent geologic articles; for the geologist.) Crater Lake, the story of its origin: Howell Williams, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1941. (This is the fascinating story of a caldera, with a history similar to that of the Jemez Mountains, as told by a park ranger to people who had never looked at rocks before.) Mining districts of New Mexico; Cerrillos: Charles L. Knaus, New Mexico Miner, Oct. 1951 (p. 13), Dec. 1951 (p. 10), and Feb. 1952 (p. 12). (An easily read summary of a well-known mining district.) Mosaic of New Mexico's scenery, rocks, and history: Paige W. Christiansen and Frank E. Kottlowski, New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Scenic Trips No. 8, 1967. (Descriptions of geology of Santa Fe area and the rest of the state, as well as articles on history, plants, animals, and other interesting facets of New Mexico.) Geology and water resources of the Santa Fe area, New Mexico: Zane Spiegel and Brewster Baldwin with contributions by other authors, U.S. Geological Survey, Water-Supply Paper 1525, 1963. (Technical description of geology, water resources, and geophysics of the Santa Fe area.) TOPOGRAPHIC MAPS Topographic maps are available for about 60 per cent of the State of New Mexico. These maps, prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey, show cultural and drainage features, such as houses, wells, roads, streams, and arroyos, and they depict the topography by contour lines of elevation. Earlier maps have been on a scale of either 1 or 2 miles to the inch. Currently, however, much of northcentral New Mexico is being mapped on a scale of 2000 feet to the inch, including the area around Santa Fe. Each map costs only 50 cents and is available from either the U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Denver, Colorado 80225, or from the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Socorro, New Mexico 87801. The maps should be ordered by quadrangle name; these names are listed on the index to mapping. The latter is available without charge from either of the two agencies.