3 In Vivo Two-Photon Laser Scanning Microscopy with

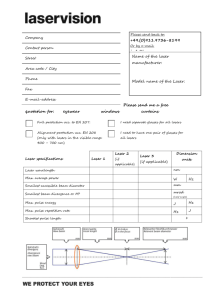

advertisement