Disordered p-n junction in graphene M. M. Fogler, L. I. Glazman,

advertisement

Disordered p-n junction in graphene

M. M. Fogler,1 L. I. Glazman,2, 3 D. S. Novikov,2, 3 and B. I. Shklovskii3

arXiv:0710.2150v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 11 Oct 2007

1

Department of Physics, University of California San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093

2

Department of Physics, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511

3

W. I. Fine Theoretical Physics Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455

(Dated: October 11, 2007)

We evaluate the resistance of a gate-tunable graphene p-n junction, in which the gradient of the

carrier density is controlled by the gate voltage. Depending on this gradient and on the density of

charged impurities, the junction resistance is dominated by either diffusive or ballistic contribution.

We find the conditions for observing ballistic transport.

PACS numbers: 81.05.Uw, 73.63.-b, 73.40.Lq

Graphene is a new material whose unique electronic

structure endows it with many unusual properties [1]. A

monolayer graphene is a gapless two-dimensional (2D)

semiconductor with a massless electron-hole symmetric

spectrum near the corners of the Brillouin zone, ǫ(k) =

±~v|k|, where v ≈ 108 cm/s. The concentration of these

“Dirac” quasiparticles can be accurately controlled by

the electric field effect [2, 3]. An exciting experimental development is the ability to apply such fields locally, by means of submicron gates. Using this technique, graphene p-n junctions (GPNJ) have been recently

demonstrated [4, 5, 6].

Even within idealized models that neglect disorder and

electron interactions, GPNJ were predicted to display a

number of intriguing phenomena. They include Klein

tunneling [7, 8, 9], Veselago lensing [10], microwaveinduced [11] and Andreev [12] reflection, and strong ballistic magnetoresistance [8, 13]. Nontrivial corrections to

these predictions and the potential for new physics are

expected when interactions and disorder are included in

the model. For example, long-range Coulomb interactions are responsible for nonlinear screening in GPNJ,

which can modify its resistance substantially [14]. The

purpose of this paper is to investigate how the junction

resistance is affected by disorder. We show that in existing GPNJ this effect is indeed strong and suggest what

can be done to reduce it in future.

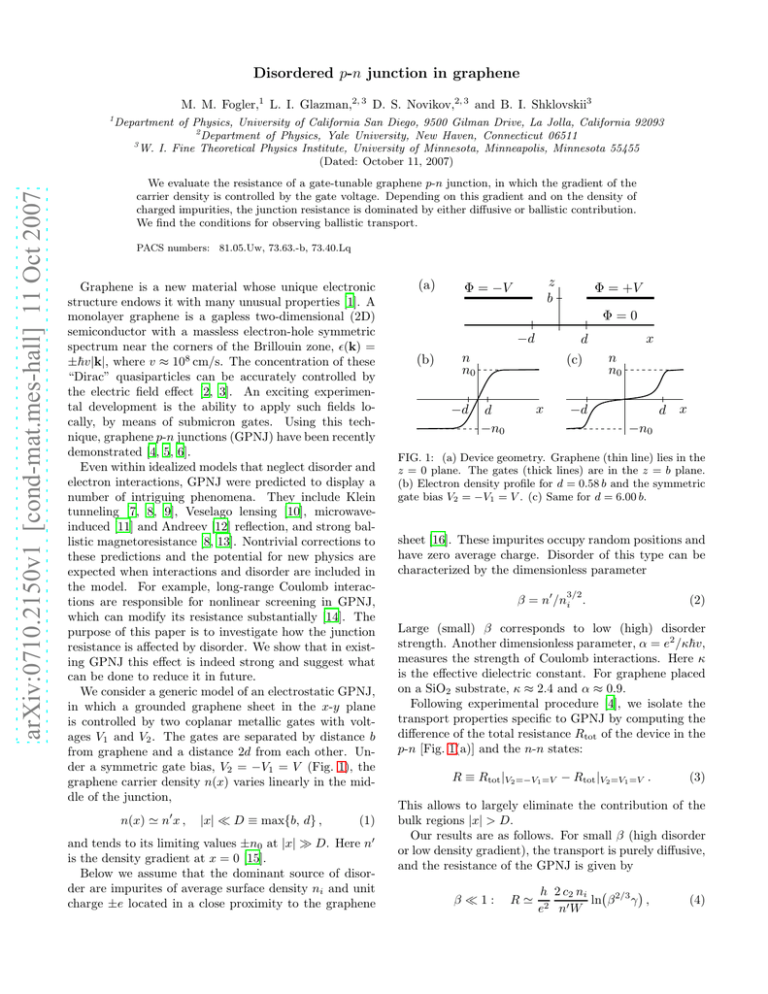

We consider a generic model of an electrostatic GPNJ,

in which a grounded graphene sheet in the x-y plane

is controlled by two coplanar metallic gates with voltages V1 and V2 . The gates are separated by distance b

from graphene and a distance 2d from each other. Under a symmetric gate bias, V2 = −V1 = V (Fig. 1), the

graphene carrier density n(x) varies linearly in the middle of the junction,

n(x) ≃ n′ x ,

|x| ≪ D ≡ max{b, d} ,

(1)

and tends to its limiting values ±n0 at |x| ≫ D. Here n′

is the density gradient at x = 0 [15].

Below we assume that the dominant source of disorder are impurites of average surface density ni and unit

charge ±e located in a close proximity to the graphene

(a)

z

b

Φ = −V

Φ = +V

Φ=0

(b)

−d

n

n0

−d

(c)

x

d

−n0

x

d

−d

n

n0

d x

−n0

FIG. 1: (a) Device geometry. Graphene (thin line) lies in the

z = 0 plane. The gates (thick lines) are in the z = b plane.

(b) Electron density profile for d = 0.58 b and the symmetric

gate bias V2 = −V1 = V . (c) Same for d = 6.00 b.

sheet [16]. These impurites occupy random positions and

have zero average charge. Disorder of this type can be

characterized by the dimensionless parameter

3/2

β = n′ /ni .

(2)

Large (small) β corresponds to low (high) disorder

strength. Another dimensionless parameter, α = e2 /κ~v,

measures the strength of Coulomb interactions. Here κ

is the effective dielectric constant. For graphene placed

on a SiO2 substrate, κ ≈ 2.4 and α ≈ 0.9.

Following experimental procedure [4], we isolate the

transport properties specific to GPNJ by computing the

difference of the total resistance Rtot of the device in the

p-n [Fig. 1(a)] and the n-n states:

R ≡ Rtot |V2 =−V1 =V − Rtot |V2 =V1 =V .

(3)

This allows to largely eliminate the contribution of the

bulk regions |x| > D.

Our results are as follows. For small β (high disorder

or low density gradient), the transport is purely diffusive,

and the resistance of the GPNJ is given by

β≪1:

R≃

h 2 c2 n i

ln β 2/3 γ ,

e 2 n′ W

(4)

2

where W is the length of the device in the y-direction,

the coefficient c2 is discussed below, and γ is defined by

γ ≡ (n′ )1/3 D ≫ 1 .

(5)

The condition γ ≫ 1, which is satisfied in experiment [4, 5, 6], ensures that the density n(x) varies across

the GPNJ slowly enough, D = max{d, b} ≫ kF−1 (n0 ),

to justify its evaluation by

pmeans of classical electrostatics [14]. Here kF (n) = π|n| is the local Fermi wave

vector. Equation (4) is written for β 2/3 γ ≫ 1, i.e., for

n0 ≫ ni , where the GPNJ is still well-defined despite

random fluctuations of the electron density n(x, y) due

to disorder.

In the opposite regime, β ≫ 1, the GPNJ resistance

β≫1 :

R = Rbal + Rdif

(6a)

is the sum of the ballistic and the diffusive contributions,

c1

h

, c1 ≈ 1.0 ;

e2 α1/6 (n′ )1/3 W

γ

h 2 c2 n i

ln 4/3 , γ ≫ β 4/3 .

≃ 2 ′

e nW

β

Rbal =

(6b)

Rdif

(6c)

Equations (4) and (6c) are valid with logarithmic accuracy and match at β ∼ 1. The ballistic contribution

dominates, R ≃ Rbal ≫ Rdif , provided

β≫

2α1/6 c2

ln

c1

γ

β 4/3

3/2

.

(7)

Realistically, the “large” logarithmic factor here is ∼ 2.

Thus the right-hand side of Eq. (7) is about 0.3–0.5. In

comparison, we estimate for recent experiments [4, 6] β ∼

0.5. This puts them in the crossover regime where Rbal ∼

Rdif . (The reported data suggests Rbal W ∼ Rdif W ∼

1 Ω · cm). To move deeper into the ballistic regime one

should either increase n′ or decrease ni .

Below we first consider electrostatics of the gatetunable junction, and then evaluate its resistance.

Electrostatics.— Electron density in graphene is related to the electrostatic potential Φ(x, z) by the Gauss

law, n(x) = (κ/4π)∂z Φ(x, +0). To find Φ and n we can

treat graphene as an ideal conductor. (For the discussion of this approximation, see Refs. [14] and [17].) The

calculation can be done using the conformal mapping

π

a+w

(8)

= (x + iz) ,

2w + ln

a−w

b

which transforms the upper half-plane z > 0 with the

branch cuts along the gates [cf. Fig. 1(a)] to the upper

half-plane of a complex variable w = w(x, z). Here a is

found from

p

√

√

a(a + 1) + ln( a + a + 1 ) = πd/(2b) .

(9)

The graphene sheet, the left gate, and the right gate

are mapped onto the intervals −a < w < a, w < −a,

and w > a, respectively, of the real axis. Therefore, the

sought potential is given by

Φ(x, z) = (1/π) Im [V1 ln(a + w) − V2 ln(a − w)] . (10)

Using these equations and simple algebra, we find

n(x) =

κ (V2 + V1 )a + (V2 − V1 )w(x)

,

8πb

a(a + 1) − w2 (x)

(11)

where w(x) stands for the real quantity w(x, z = 0) defined by Eq. (8). For the symmetric gate bias we obtain

n0 (V )w(x)

,

a(a + 1) − w2 (x)

n(x) =

V2 = −V1 = V ,

(12)

in which case the density gradient at x = 0 is given by

n′ =

π n0 (V )

,

2b (1 + a)2

n0 (V ) =

κV

.

4πb

(13)

Examples of n(x) computed according to Eqs. (8) and

(12) are plotted in Fig. 1(b) and (c).

Ballistic resistance.— The resistance Rbal of a clean

GPNJ is related [8] to the electric field at the p-n

interface. To compute this field one has to go beyond electrostatics of ideal conductors and take into account nonlinear screening at the p-n interface. Equation (6b) for Rbal was derived from this analysis in

Ref. [14]. A simple explanation of this result can be

given in the case α ∼ 1, where Rbal can be qualitatively understood as the

ballistic resistance of a system with W kF n(xtun ) transmitting channels: Rbal ∼

(h/e2 )(kF W )−1 ∼ (h/e2 )(xtun /W ). Here the effective

“width” of the p-n interface

xtun = α−1/6 (n′ )−1/3

(14)

is found from the condition that it is of the order of

the quantum uncertainty

in the quasiparticle coordinate,

xtun ∼ kF−1 n(xtun ) . (In Ref. [14] xtun was denoted by

xTF .) The quasiparticles that manage to get inside the

strip |x| < xtun cross the p-n boundary without tunneling

suppression [8].

Below we consider the resistance (3) of a symmetrically

biased GPNJ, V2 = −V1 = V . The transport is either

diffusive or ballistic depending on the gradient (2).

Diffusive transport, β ≪ 1.— Introduction of charged

impurities results in the finite carrier mean free path

l(n) = 1/ni Λ ,

Λ = 2πc2 (α)/kF (n) ,

(15)

where Λ is the transport cross-section for Coulomb impurities [18, 19, 20, 21]. For α ≪ 1 (graphene on large-κ

substrate), c2 = πα2 /2, while for α ≈ 1 (SiO2 substrate),

c2 ∼ 0.1 [22]. Impurities act as independent scatterers if

|n| ≫ ni . The corresponding resistivity is [18, 19, 20, 21]

ρ(n) =

h ni

h

= 2

c2 (α) ,

2e2 kF l

e |n|

|n| ≫ ni .

(16)

3

(a)

x

0

x tun x flc

x flc

D

x bal

x

(b)

0 x tun

D

FIG. 2: A sketch of the characteristic lengthscales in a GPNJ

for (a) β ≪ 1 and (b) β ≫ 1. Only the x > 0 side of the junction is shown. The diffusive region is hatched. Parameters

xtun and xflc are indicated by the dashed lines in the regimes

(a) and (b), respectively, because they do not have a direct

physical meaning in these cases.

It is legitimate to treat ρ n(x) as the local x-dependent

resistivity if the density gradient is sufficiently small, such

that l(n)|∂x n| ≪ n. For β ≪ 1 this condition is satisfied

at all |x| ≫ ni /n′ where Eq. (16) is itself valid, |n| ≫

ni . On the other hand, in the strip |x| . xflc = ni /n′

[Fig. 2(a)], the disorder-induced fluctuations of the local

density overwhelm the average n(x) ≃ n′ x dependence.

As a result, Eq. (16) no longer holds.

Since the transport remains diffusive in this strip (certainly, it cannot be ballistic because of strong disorder) [23], we can assume that the corresponding local

resistivity is of the order of its bulk value ρ ∼ h/e2 at

the charge neutrality point [3]. This allows us to estimate

the resistance of this region as ∼ (h/e2 )(xflc /W ).

According to our definition (3), the GPNJ resistance is

the difference of the total resistances in the p-n and n-n

configurations. It is convenient to write it as R = Rdif (0),

where

Z∞

2

dx̃ ρ(x̃)|V1 =−V2 − ρ(x̃)|V1 =+V2 . (17)

Rdif (x) =

W

x

Using Eqs. (8), (12), (16), and the expression

n(x) =

n0 (V )a

,

a(a + 1) − w2 (x)

V1 = V2 = V ,

(18)

for the charge profile in the n-n state that follows from

Eq. (11), the integral in Eq. (17) can be transformed to

n0

h 2c2 ni

, x & xflc . (19)

ln

Rdif (x) ≃ 2 ′

e nW

(a + 1)n′ x

This resistance is logarithmically larger than

(h/e2 )(xflc /W ).

In other words, the resistance of

the |x| < xflc strip is much smaller than that of the rest

of the junction. Therefore, R ≃ Rdif (xflc ), which leads

to Eq. (4).

Ballistic transport, β ≫ 1.— Here the carrier density

n(x) varies with x more rapidly. As a result, the diffusive

approximation breaks down inside the strip |x| . xbal

whose width is given by the condition l[n(xbal )] ∼ xbal ,

xbal ∼

1 n′

.

4πc22 n2i

(20)

The carrier density at x = xbal is still high, n(xbal ) ≫ ni ,

so that at |x| > xbal Eq. (16) applies. Thus, the diffusive contribution to the resistance is Rdif ≃ Rdif (xbal ),

leading to Eq. (6c). [The extra factor β −2 under the

logarithm in Eq. (6c) vs. (4) comes from xbal ∼ β 2 xflc .

Note, however, that xflc has no direct physical meaning

if β ≫ 1.]

In contrast, within the strip |x| < xbal the transport is

ballistic: the local mean-free path l[n(x)] nominally exceeds |x|, so that quasiparticles reach the p-n interface

largely without experiencing impurity scattering. We

now note that the tunneling strip (20) is located deep

inside this ballistic region,

xtun ∼

4πc22 xbal

≪ xbal ,

α1/6 β 4/3

(21)

see Fig. 2(b). Therefore, the transmission problem is

reduced to the clean case [14], yielding Eq. (6b) for the

ballistic resistance Rbal .

Due to the large logarithmic factor in Rdif [Eq. (6c)],

the ballistic contribution in Eq. (6a) starts to dominate

the diffusive one only when β exceeds a logarithmically

large threshold, Eq. (7). In other words, the ballistic

transport is observable only for a GPNJ with a sufficiently large concentration gradient.

Let us illustrate geometrical requirements imposed by

the criterion (7) assuming α ∼ 1. Consider first the case

of widely separated gates, d = 1 µm and b = 50 nm. For

the impurity concentration ni ∼ 1012 cm−2 (presumed

to be a typical number), we get β ≈ 0.005 even for a

relatively high maximum density n0 ∼ 10ni ∼ 1013 cm−2 .

Thus, in this kind of a GPNJ one cannot observe ballistic

transport. On the other hand, in a shorter device, b ≈

d ≈ 40 nm, such as that of Ref. [4], the minimum density

needed to reach the ballistic regime, β ∼ 0.5, is close to

the experimental value n0 = 2 × 1012 cm−2 [4] at which

evidence of the ballistic resistance was indeed seen.

To conclude, the presence of charged disorder results

in the two distinct transport regimes in the junction.

The GPNJ resistance in the ballistic regime is given by

Eqs. (6), and in the diffusive regime by Eq. (4). In the

current experiments [4, 5, 6], the ballistic regime was

reached only marginally. For ballistic devices one should

aim at larger electron density gradients n′ and smaller

impurity concentration to satisfy the condition (7). The

requirement on n′ becomes less stringent for substrates

of high dielectric constant κ, which reduces the weight

c2 ∝ α2 ∝ κ−2 of Coulomb scattering. Finally, the

present approach can be extended to other geometries

that involve local gate control of graphene nanostructures

(asymmetric junctions, multiple gates, etc.).

This work is supported by the Grants NSF DMR0706654 (M. F.) and NSF DMR-0749220 (L. G., D. N.).

M. F. thanks the W. I. Fine TPI for hospitality.

4

[1] A. K. Geim and K. S. Novoselov, Nature Mater. 6, 183

(2007); A. H. Castro Neto, F. Guinea, N. M. R. Peres,

K. S. Novoselov, and A. K. Geim, arXiv:0709.1163

(2007).

[2] K. S. Novoselov, A. K. Geim, S. V. Morozov, D. Jiang,

Y. Zhang, S. V. Dubonos, I. V. Grigorieva, and A. A.

Firsov, Science 306, 666 (2004).

[3] K. S. Novoselov, A. K. Geim, S. V. Morozov, D. Jiang,

M. I. Katsnelson, I. V. Grigorieva, S. V. Dubonos, and

A. A. Firsov, Nature 438, 197 (2005).

[4] B. Huard, J. A. Sulpizio, N. Stander, K. Todd, B. Yang,

and D. Goldhaber-Gordon, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 236803

(2007).

[5] B. Özyilmaz, P. Jarillo-Herrero, D. Efetov, D. A. Abanin,

L. S. Levitov, and P. Kim, arXiv:0705.3044 (2007).

[6] J. R. Williams, L. DiCarlo, and C. M. Marcus, Science

317, 638 (2007).

[7] M. I. Katsnelson, K. S. Novoselov, and A. K. Geim, Nature Phys. 2, 620 (2006).

[8] V. V. Cheianov and V. I. Fal’ko, Phys. Rev. B 74, 041403

(2006).

[9] J. M. Pereira, Jr., V. Mlinar, F. M. Peeters, and

P. Vasilopoulos, Phys. Rev. B 74, 045424 (2006).

[10] V. V. Cheianov, V. I. Fal’ko, and B. L. Altshuler, Science

315, 1252 (2007).

[11] M. V. Fistul and K. B. Efetov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,

256803 (2007).

[12] A. Ossipov, M. Titov, and C. W. J. Beenakker, Phys.

Rev. B 75, 241401(R) (2007).

[13] A. V. Shytov, N. Gu, and L. S. Levitov, arXiv:0708.3081

(2007).

[14] L. M. Zhang and M. M. Fogler, arXiv:0708.0892 (2007).

[15] Note that n′ stands for the density gradient computed

classically. Quantum effects decrease true n′ [14].

[16] J. H. Chen, C. Jang, M. S. Fuhrer, E. D. Williams, and

M. Ishigami, arXiv:0708.2408 (2007).

[17] See M. M. Fogler, D. S. Novikov, and B. I. Shklovskii,

arXiv:0707.1023 (2007) and references therein.

[18] T. Ando, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 074716 (2006).

[19] K. Nomura and A. H. MacDonald, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,

076602 (2007).

[20] E. H. Hwang, S. Adam, and S. Das Sarma, Phys. Rev.

Lett. 98, 186806 (2007).

[21] D. S. Novikov, arXiv:0706.1391 (2007); Appl. Phys. Lett.

91, 102102 (2007).

[22] Treating the impurity screening within the Random

Phase Approximation (RPA) and calculating the scattering cross-section perturbatively yields c2 (0.9) ≈ 0.05

[18, 20]. For α ∼ 1 this calculation is likely to underestimate c2 . Using the RPA at the Dirac point and treating scattering off the resultant Coulomb potential exactly

yields c2 (0.9) ≈ 0.26 (when averaged over the donors and

acceptors) [21]. This is likely to overestimate the resistivity. Thus, the true c2 (α ∼ 1) is probably close to 0.1.

[23] In addition, we assume that the temperature is not too

low and neglect any localization effects.