50-STATE SURVEY OF PROTECTIONS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASERS OF CONTAMINATED PROPERTY

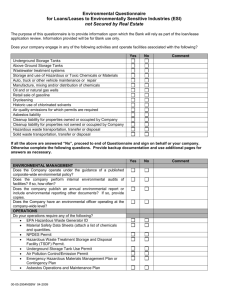

advertisement