PATTERN JURY INSTRUCTIONS (Civil Cases) Prepared by the

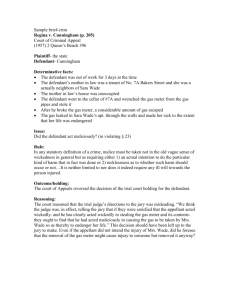

advertisement