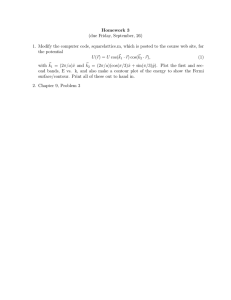

/I

advertisement