Improving referral pathways between urgent and emergency services in England

advertisement

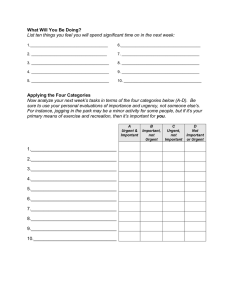

Transforming Urgent and Emergency Care Services in England Improving referral pathways between urgent and emergency services in England Advice for Urgent and Emergency Care Networks NHS England INFORMATION READER BOX Directorate Medical Nursing Finance Commissioning Operations Trans. & Corp. Ops. Publications Gateway Reference: Patients and Information Commissioning Strategy 04075 Document Purpose Guidance Document Name Improving referral pathways between urgent and emergency services in England Author Urgent and Emergency Care Review Programme Team Publication Date November 2015. Target Audience CCG Clinical Leaders, CCG Accountable Officers, Care Trust CEs, Foundation Trust CEs , NHS England Regional Directors, NHS England Directors of Commissioning Operations, Emergency Care Leads, Directors of Children's Services, NHS Trust CEs, System Resilience Groups; Urgent and Emergency Care Networks Additional Circulation List CSU Managing Directors, Medical Directors, Directors of Nursing, Local Authority CEs, Directors of Adult SSs, NHS Trust Board Chairs, Directors of Finance, GPs, Special HA CEs Description This document is designed to help Urgent and Emergency Care (UEC) Networks and System Resilience Groups (SRGs) to improve the flow of patients and information within the urgent and emergency care system by supporting an enhanced and consistent approach to the referral of patients between healthcare professionals and providers. Cross Reference Superseded Docs (if applicable) Action Required Timing / Deadlines (if applicable) Contact Details for further information Revised planning guidance for 2015/16; Five Year Forward View N/A Best practice N/A england.urgentcarereview@nhs.net 0 0 Document Status This is a controlled document. Whilst this document may be printed, the electronic version posted on the intranet is the controlled copy. Any printed copies of this document are not controlled. As a controlled document, this document should not be saved onto local or network drives but should always be accessed from the intranet. 2 Document Title: Improving referral pathways between urgent and emergency services in England Subtitle: Advice for Urgent and Emergency Care Networks Version number: FINAL 1 First published: November 2015 Updated: (only if this is applicable) Prepared by: UEC Review Team The National Health Service Commissioning Board was established on 1 October 2012 as an executive non-departmental public body. Since 1 April 2013, the National Health Service Commissioning Board has used the name NHS England for operational purposes. Equality and Health Inequalities Promoting equality and addressing health inequalities are at the heart of NHS England’s values. Throughout the development of the policies and processes cited in this document, we have: Given due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimisation, to advance equality of opportunity, and to foster good relations between people who share a relevant protected characteristic (as cited under the Equality Act 2010) and those who do not share it; and Given regard to the need to reduce inequalities between patients in access to, and outcomes from healthcare services and to ensure services are provided in an integrated way where this might reduce health inequalities. Urgent and Emergency Care Networks are reminded to pay due regard to the two duties above when this guidance is implemented locally. Information Governance Safe and efficient patient care requires effective, timely and appropriate transfer of key information that follows the patient through the healthcare system. This is particularly important in the urgent and emergency care system where, by definition, the patient is accessing care from outside of their routine care providers. The informed consent of patients should normally be sought and obtained before accessing or sharing information about them. This informed consent needs to ensure that the patient understand who will access their data and for what purposes. If they are adults and lack the capacity to make these decisions, those decisions should be 3 made in their best interests in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its Code of Practice. If they are children aged under 16, those decisions should be made by someone with parental responsibility for them, unless they are Gillick competent and, after applying the Fraser Guidelines it is best interests to respect their decision. If they are children aged 16 or 17, the principles set out in paragraph 12.13 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice should be followed. The wishes of children (and those with parental responsibility for them) can/should be overridden in their best interests to save them from significant harm; the wishes of adults with capacity cannot be overridden unless overriding their wishes may prevent serious crime Significant abuse or neglect are/may be crimes. All of the above is subject to what might happen in an emergency when people cannot make, or cannot properly be expected to make, decisions. When that is so, all decisions to do with their immediate care and welfare should be made in their best interests in accordance with chapter 5 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice. 4 Contents 1 Document summary ............................................................................................ 6 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England ..................... 6 Purpose ......................................................................................................... 7 Audience ....................................................................................................... 7 Structure ........................................................................................................ 7 How it will be used ......................................................................................... 8 Clinical governance ....................................................................................... 8 2 Introduction.......................................................................................................... 9 3 Description of the proposed changes ................................................................ 10 3.1 4 How this works in practice: ................................................................................ 11 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 5 HealthPathways .......................................................................................... 11 The Initial Response Service ....................................................................... 12 Paramedic Pathfinder .................................................................................. 13 Direct referral to a diabetic specialist nurse team ........................................ 14 Implementation .................................................................................................. 15 5.1 6 Guidance on referrals across the UEC system ............................................ 10 Principles of enhanced referral .................................................................... 15 Benefits ............................................................................................................. 16 6.1 6.2 Benefits to the system ................................................................................. 16 Benefits to the patient .................................................................................. 16 7 Summary and Conclusion ................................................................................. 17 8 Appendix 1: Case illustrations ........................................................................... 18 Case 1................................................................................................................... 18 Case 2................................................................................................................... 18 Case 3................................................................................................................... 19 5 1 Document summary 1.1 Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England The NHS Five Year Forward View (5YFV) explains the need to redesign urgent and emergency care services in England for people of all ages with physical and mental health problems, and sets out the new models of care needed to do so. The urgent and emergency care review (the review) details how these models of care can be achieved through a fundamental shift in the way urgent and emergency care services are provided to all ages, improving out-of-hospital services so that we deliver more care closer to home and reduce unnecessary hospital attendances and admissions. We need a system that is safe, sustainable and that provides high quality care consistently. The vision of the review is simple: For adults and children with urgent care needs, we should provide a highly responsive service that delivers care as close to home as possible, minimising disruption and inconvenience for patients, carers and families. For those people with more serious or life-threatening emergency care needs, we should ensure they are treated in centres with the right expertise, processes and facilities to maximise the prospects of survival and a good recovery. As part of the review, a number of products are being developed to help create the conditions for new ways of working to take root and when combined, deliver an improved system of urgent and emergency services. The review proposes that five key changes need to take place in order for this to be achieved. These are: Providing better support for people and their families to self-care or care for their dependants. Helping people who need urgent care to get the right advice in the right place, first time. Providing responsive, urgent physical and mental health services outside of hospital every day of the week, so people no longer choose to queue in hospital emergency departments. Ensuring that adults and children with more serious or life threatening emergency needs receive treatment in centres with the right facilities, processes and expertise in order to maximise their chances of survival and a good recovery. Connecting all urgent and emergency care services together so the overall physical and mental health and social care system becomes more than just the sum of its parts. NHS England is collaborating with patients and partners from across the system to develop a suite of guidance documents and tools to promote best practice and 6 support commissioners and providers in achieving a fundamental shift towards new ways of working and models of care. These guidance documents are being developed as a suite entitled ‘Transforming Urgent and Emergency Care Services in England’ and are designed to be read together. The suite comprises the following components: Role and establishment of Urgent and Emergency Care Networks (UECNs), published June 2015. Clinical models for ambulance services. Improving referral pathways between urgent and emergency services in England. (This document.) Safer, faster, better: good practice in delivering urgent and emergency care’, published August 2015. This good practice guide focuses on the safe and effective care of people with urgent and emergency health problems who may seek or need specialist hospital based services. Urgent and emergency care: financial modelling methodology. Other products to support include a Directory of Services (DoS) – a tool to include all available services that can be referred to, and Commissioning Standards for Integrated Urgent Care (that includes the NHS 111 contact number), which has been published, as well as its supporting documents, to be published. These will include the Integrated Urgent Care Payment annex; Integrated Urgent Care Contract Alignment Plan; NHS England Integrated Urgent Care (NHS 111 Telephony) National Business Continuity Policy; Procurement Guidance and Integrated Urgent Care Model (Financial Model Tool). 1.2 Purpose This document is designed to help UECNs to improve the flow of patients and information within the urgent and emergency care system by supporting an enhanced and consistent approach to the referral of patients between healthcare professionals and providers. 1.3 Audience This document is intended to be used by UECNs. It provides advice for commissioners on the benefits of enhancing referrals within the urgent and emergency care system, and advice for providers on good practice and how this might be implemented, understanding that this will also be determined by local need. Membership of UECNs is outlined in the Role and Establishment of Urgent and Emergency Care Networks. 1.4 Structure The document begins with an introduction explaining why the move to a more cohesive and integrated approach to the delivery of care is desirable, and how 7 different parts of the health service can collaborate to deliver this. It goes on to describe the proposed changes in patient referral across the urgent and emergency care system, and the benefits of implementing these changes. 1.5 How it will be used The 5YFV emphasised the importance of how we will increasingly need to manage health care systems through networks of care; not just by, or through, individual organisations. UECNs are expected to define consistent pathways with equitable access across urgent and emergency care. Commissioners should utilise the principles outlined in this document, tailoring them to meet local need as identified by the networks across England. 1.6 Clinical governance At an operational level, the patient pathways described under each service specification will define clinical accountability according to the patient’s needs and their referral pathway. 8 2 Introduction The demand for urgent and emergency care has increased significantly over the last decade. Patient attendance at hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) has increased by more than two million, to 16 million annually, and emergency admissions to hospitals have increased by 31%. Attendance at walk-in centres and minor injury units has increased 12% annually, and the number of 999 calls to the ambulance service has increased from 4.9 to 9 million calls per year. As the population is living longer, and has increasingly complex medical needs, this demand is only predicted to increase. The annual cost to the NHS of admissions for conditions that are appropriate for ambulatory care was estimated to be £1.42 billion in 2009/10, and accounted for 15.9% of all emergency admissions to hospital.1 Many patients who seek emergency input from the NHS111 and ambulance services with ambulatory care sensitive (ACS) conditions would benefit from referral to more appropriate care pathways without admission to hospital.2 There is emerging evidence that the 999 activity of patients on clinical registers is predictable, and access to data and appropriate and expedient care can reduce conveyance by over 20%. In 2010, in the North West alone, more than 18,000 chronic obstructory pulmonary disease (COPD) patients who accessed urgent and emergency care were admitted to hospitals, of which 11,000 could have been treated in their community via primary and community services. 3 Additionally, mental illness is estimated to be the primary cause of around 5% of ED attendances, and alcohol-misuse a further 10%. 4 It is estimated that there are around 150,000 hospital attendances for self-harm each year. Approximately 90% of these patients have a diagnosable mental health condition.4 Often, the physical symptoms are treated without managing the underlying mental health problem resulting in future multiple attendances. At present ambulance and other urgent care professionals are not uniformly empowered to refer patients to community or specialist services. Urgent Care Centres (UCCs) frequently do not permit paramedics to refer patients to them on the assumption that the ambulance service does not deal with minor injuries,3 and hospitals, in turn, may not accept referrals from non-medical healthcare professionals working in UCCs. Paramedics report that an absence of appropriate referral pathways can lead to duplicated and unnecessary activities which consume time and resources, reduce 1 Tian, Y, Dixon A, Gao H. Emergency hospital admissions for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Data briefing. Kings Fund. 2012. Available at http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/data-briefing-emergency-hospital-admissions-for-ambulatory-care-sensitive-conditions-apr-2012.pdf 2 Paramedic Pathfinder and Community Care Pathways, North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust. Last accessed 30/7/15. Available at https://www.nwas.nhs.uk/DownloadFile.ashx?id=286&page=16586 3 Health Committee. Written evidence from the College of Paramedics (ES 17). May 2013. Last accessed 30/7/15. Available at http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmhealth/171/171vw13.htm 4 Liaison Psychiatry in the Modern NHS, Centre for Medical Health (2012) Available at: http://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/liaison_psychiatry.aspx?ID=665 9 efficiency and almost certainly affects patient perceptions of a joined-up NHS.3 3 Description of the proposed changes 3.1 Guidance on referrals across the UEC system In order to facilitate an improved flow of patients and information within the UEC system, all registered health and social care professionals within physical and mental health (referred to in this document using the general term ‘practitioner’), following telephone consultation or face-to-face contact with a patient, should be empowered, based on protocols developed and agreed locally, to make direct referrals and/or appointments for patients with: The patient’s registered general practice or corresponding out of hours (OOH) service; Urgent Care Centres; Emergency Departments in Emergency Centres and in Emergency Centres with Specialist Services; Mental health crisis services and community mental health teams; Specialist clinicians, if the patient is under the active care of that specialist service for the condition which has led to them accessing the urgent and emergency care system. UECNs are encouraged to define the exact referral pathways available to each professional working within their network. The underpinning documentation to support this proposed change is described further in Commissioning Standards Integrated Urgent Care (for NHS 111 services). The diagram below illustrates what a functionally integrated urgent care service including an urgent care clinical hub might look like: 10 This integrated care model is also described in more detail in Commissioning Standards - Integrated Urgent Care (for NHS111 services). 4 How this works in practice: 4.1 HealthPathways Developed in 2008 in Canterbury, New Zealand, HealthPathways is described as the ‘most innovative and most effective’ change to the health and social care system.5 Essentially, HealthPathways are local agreements on best practice whereby hospital doctors, GPs, nurses and allied health professionals have designed patient pathways and treatment plans in cohesion. These are managed within the community and incorporate guidelines on referrals, available resources for GPs to avoid unnecessary referrals and indicate suitable tests to be conducted before making a referral either in the community or to a hospital. 5 The quest for integrated health and social care - A case study in Canterbury New Zealand. Timmins, N & Ham, C (2013) Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2013/09/right-track-how-healthpathways-are-improving-care-canterbury-new-zealand 11 Canterbury has more than 480 pathways which are routinely reviewed every year and regularly audited. Referrals are directed through an Electronic Shared Management System which is used to request tests as an outpatient, to make community assessments and to request specialist advice. An Acute Demand Management System (ADMS) has been implemented which provides general practice with a support structure for patients who may need medical support but otherwise do not need to be referred to a hospital. It also offers support for the hospital to refer patients from the emergency department to more appropriate settings, thereby benefiting patients who require tests or observation but do not require admission to hospital. As a result patients can be managed close to home where it is safe and appropriate to do so. How the ADMS works in practice – an example A specific programme for COPD was introduced after analysis showed that once patients reached the emergency department they had very high admission rates. Patients are given care plans and something as simple as a fridge magnet which has their normal oxygen saturation and exercise tolerance on it. This allows the ambulance service to know what is ‘normal’ for the patient, so that – supported by telephone access to a respiratory physician – paramedics can decide whether the patient needs to go to the emergency department or can be managed in the community by the GP or by acute demand management. In the winter of 2012, Canterbury estimates that some 40 per cent of COPD patients who would previously have been taken to the emergency department were diverted to other forms of care’.6 Other innovative changes include an Electronic Shared Care Record View (eSCRV), a 24 hour General Practice service where GPs responsible for out of hours care work alongside a nurse triage system, and a number of centers that have extended opening hours. A falls management system has been implemented, as has a pharmacy-linked medication management system which conducts a review of patients prescribed multiple drugs. Results Canterbury demonstrates low rates for acute medical admissions compared to other health boards in New Zealand. Its average length of stay is low, and its acute readmission rate is also low. These innovations have led to a demonstrably reduced demand on hospital resources and a flattening and reduction of the demand curve across health and social care, due to improved integration between hospital, primary care and community services. Overall this has resulted in better and more integrated care for patients, resulting in ‘the right care in the right place at the right time’. 4.2 The Initial Response Service 12 Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust have implemented an assessment response team providing a single entry point for patients with mental health issues via a 24/7 telephone line. The service provides advice for patients on their current presentation and allows referral into other services so that patients can access the right care for their needs, without the need to default to Accident and Emergency Departments. The service also provides advice to General Practice on presenting patients, so GPs feel better supported in managing patients with mental health issues.6 Nurses triage through telephone consultation. This results in a clinical decision, identifying the most appropriate intervention for the individual which could be: Referral to rapid response for face to face triage; home visits undertaken within one hour; Referral to GP services to manage presenting symptoms; Referral to existing Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment Teams for crisis management; Simply providing telephone advice on managing the current situation. Staff meet daily to discuss patient referrals, which enables the large proportion of referrals that are not urgent or in mental health crisis to be booked into the most appropriate outpatient service or proceed with an agreed management plan. Results Following implementation of the assessment response team, the Trust report: 100% of service users surveyed reported satisfaction with the response and would recommend the service to a friend; A reduction in the number of urgent calls to the ambulance service, improved response times from the Crisis Team and a reduction in four-hour breaches; Reduced avoidable harm due to reduced referrals ‘bouncing’ around the system; 100 per cent of GPs said their calls were answered quickly and the team met their needs. 4.3 Paramedic Pathfinder The North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) implemented Paramedic Pathfinder in 2012. Based on the Manchester Triage System, Pathfinder is a consistent and clinically safe triage system to enable accurate face-toface assessment of individual patient needs on scene, identifying the most appropriate care pathway for that patient. This initiative has been adopted by several UK Ambulance Trusts and has enabled NWAS to increase safe care closer to home by over 10% in 3 years. 7 Pathfinder will generate one of four key outcomes which stream and direct patients based on their care needs, including: 6 The Initial Response Service, Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust. Available at: www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/media/2422305/northumberlandtyne_cs_final.pdf 7 Paramedic pathfinder and community care pathways. Available at http://www.nwas.nhs.uk/DownloadFile.ashx?id=286&page=16586 and http://www.nwas.nhs.uk/professionals/paramedic-pathfinder/#.Vegi8aHTU-I 13 Emergency department; Urgent care centre; Community or primary care pathways; Self-care. Community Care Pathways (CCPs) are one of the clinical outcomes linked to the Paramedic Pathfinder. Each individual care plan will enable ambulance paramedics to access the most effective referral and treatment option for known patients. The community care plans are prepared by the patient’s ‘case worker’ or lead clinician and are an effective alternative pathway of care for patients with long term conditions that enables paramedics to identify when referral to expert community teams may be a better option for the patient. GP Referral Scheme in Paramedic Pathfinder In 32 of the 33 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) across the North West, ambulance crews have access to a GP via a GP Referral Scheme, with patient consent, to establish if the patient is safe to be left at home, requires a GP visit or should be transported to the ED. Over the past 12 months this has greatly increased the proportion of patients successfully managed using a “See and Treat” model of care. The GPs have been funded by the local CCG, as an ED avoidance scheme. The results show that in little over a year, almost 30,000 ED attendances have been avoided, with financial savings noted in both ED attendances and acute admission costs. 4.4 Direct referral to a diabetic specialist nurse team A direct referral pathway for acute hypoglycaemic events, where patients are referred directly to a diabetic specialist nurse (DSN) by the ambulance service, has been trialled in West Yorkshire.8 Patients with acute hypoglycaemia for whom an ambulance has been called are assessed and treated on scene by the ambulance service, rather than being transported to an ED or UCC. Patients are referred directly by ambulance staff to the DSN team, who contact the patient via telephone within 7 days. Results The DSNs arranged for 76% of referred patients to be reviewed in clinic; all were provided with patient education regarding hypoglycaemia and over half had their medications altered. Following contact and review by the DSN team: 8 Walker A, James C, Bannister M, Jobes E. Evaluation of a diabetes referral pathway for the management of hypoglycaemia following emergency contact with the ambulance service to a diabetes specialist nurse team. Emerg Med J 2006;23:449-451 14 88% of patients reported in a post-treatment survey that their understanding of hypoglycaemia had improved; 73% of patients felt more able to self-manage any future hypoglycaemic episodes. Overall patient satisfaction with the care pathway and the care they had received was high. 5 Implementation Successful implementation of this guidance should be supported by the local development of direct community and acute specialist referral pathways to enable safe and effective onward care to be reliably achieved as an alternative to ED presentation and emergency hospital admission. Appropriate clinical and information governance arrangements will need to be established, and it is suggested that governance and responsibility rests with the referring practitioner until the referral has been accepted by the receiving practitioner, at which point governance and responsibility transfers. Successful implementation is also dependent on the development of a trusting, reciprocal arrangement between composite parts of the UEC system. Practitioners will need to be able to trust the referrals from other health and social care professionals without the need to re-triage. To facilitate a process of continuous quality improvement, and to provide education for those who refer, an enhanced feedback loop should be established. This will provide the practitioners who receive referrals with access to a method of feeding back to a named practitioner in the referring service. To achieve this, a senior member of clinical staff with clinical governance responsibilities should be nominated in each referring service (e.g. ambulance trust, NHS 111 provider, etc.) to act as an accessible point of contact for collating and responding to this feedback, and introducing any education and system changes that are required in response to the feedback received. In some instances a “trusted assessor” model may be implemented that, by pathway, provides senior clinical expertise and authority to support practitioners operating within that care pathway and also offers expert clinical assurance for practitioners, patients and relatives. This will help to build confidence in the enhanced referral pathway, and ensure it can be subject to regular audit and review. 5.1 Principles of enhanced referral Nothing in this guideline is intended to replace the primacy of general practice in coordinating care and referral to specialist services. 15 The referring practitioner must assess the patient either over the phone or in person prior to initiating any onward referral. Patients can only be referred to hospital specialists when they are under the active care of that specialist team for the condition that has led them to contact the urgent and emergency care system. The timing of any referral should be proportionate to clinical urgency. In many cases the utilisation of the expertise within an urgent care clinical hub may help to assess and prioritise referrals, thereby preventing system overload. 6 Benefits 6.1 Benefits to the system The benefits to the system of adopting an enhanced and consistent approach to the referral of patients include: Enabling health and social care professionals to enact previously agreed care plans, by removing potential referral barriers in the system. This reduces pressure on EDs and acute hospital beds by offering access to alternative services and pathways of care. It also reduces the use of ED as a “default service” or “safety net” when other services prove inaccessible. Management of patients within community care settings enables emergency resources to be more available and responsive to life threatening emergencies. Enabling patients with presenting mental health issues to be seen by mental health services at an earlier point, which can significantly improve chances of recovery. Financial savings may be significant, and a direct result of a reduction in ED attendance and emergency admissions, particularly for patients with care plans. Examples of this can be seen in Kirklees and Warrington where admissions for patients with a current care plan are 50% lower than pre-care plan9. Up to 40% reduction in conveyance to the ED as a result of paramedic pathfinder. 60% reduction in 999 calls for those patients with an active care plan. Avoiding ‘duplication of effort’; for example when the patient is assessed by multiple services before reaching a point of definitive care. NHS England will be releasing in the later part of the year an Urgent and Emergency Care Review financial modelling methodology document – this document will provide further guidance for localities on how they can model and understand the potential financial implications of improving referral pathways. 6.2 Benefits to the patient The benefits to the patient include: 9 Avoiding unnecessary and inappropriate delays to the appropriate care; Avoiding duplication of assessment and additional steps in the urgent care https://www.nwas.nhs.uk/DownloadFile.ashx?id=286&page=16586 16 pathway that add no value to the patient; The patient can be guided towards the most appropriate care destination directly, by overcoming unnecessary referral restrictions and integrating elements of the urgent and emergency care system; Where the patient requires follow-up with a specialist service to which they are already known, this can be arranged directly in a timely way; Access to community care for patients who require it, such as district nursing care, community physiotherapy or review by a falls team. 7 Summary and Conclusion This guideline describes the principles underpinning a system of enhanced referral and improved patient pathways achieved by removing unnecessary blockages and reducing duplication in the urgent and emergency care system. Clear and consistent feedback mechanisms are required to support this recommended service development and ensure a process of continuous quality improvement supported by education and audit. 17 8 Appendix 1: Case illustrations Case 1 ST is a nine year old child who has brittle asthma. He has previously been hospitalised on a number of occasions due to his severe and recurrent attacks. ST has regular review appointments at his local hospital in a specialist paediatric asthma clinic. It is Monday morning, and ST’s mother has observed deterioration in his condition, which has worsened further over the weekend. She dials 111 and is connected to a children’s nurse, working in an urgent care clinical hub. The nurse is able to assess ST’s condition over the telephone and assess the acuity of his attack. The nurse and ST’s mother agree that he does not need immediate hospital admission, but further specialist input is required. The nurse is able to refer ST directly to the inpatient specialist team, who arrange to see ST at the hospital outpatient clinic that afternoon. ST is seen within four hours of the 111 call by a consultant paediatric respiratory physician who prescribes a high dose of oral steroids and modifications to ST’s inhalers that rapidly improve his breathing. ST’s condition settles, and he is able to return to school the next day, avoiding a hospital admission. Case 2 JN is an 80 year old lady who lives in sheltered accommodation; she uses her emergency call bell after falling at home. When the paramedics arrive they find her on the floor, shaky and upset, with some bruising to her right shoulder. The paramedics help JN to her feet, and are able to assess the need for hospitalisation based on the injuries sustained and agree that clinically, admission to hospital is not required. The paramedics treat JNs physical injuries in her home, avoiding the need for transfer to hospital. The paramedics note that JN is taking medication to lower her blood pressure, and with her consent refer her to her GP for follow up. The referral includes a request for a review of her current medication The paramedics recognise JN’s anxiety regarding her fall, and that she is at risk of further falls. With JN’s consent they refer her to the local falls team who arrange to visit JN at home in two days’ time. The community falls team develop a personalised treatment plan with JN, which includes an exercise programme and advice on how to complete everyday tasks more safely. JN reports that her confidence has increased, and that her independence is improved as a result. JN has avoided a hospital visit and her risk of further falls; injury and hospital admission are substantially reduced as a result of these referrals. 18 Case 3 KR is a 47 year old man with schizophrenia who moved to new accommodation several months ago. He was unable to find a practice that would register him and lost contact with his community psychiatric nurse (CPN), and was unable to access his antipsychotic medication. Since then he has become progressively more withdrawn, and has been seen by his new neighbours to be muttering to himself. KR calls NHS111 with a sore throat, which he feels has been caused by poisons that his neighbours are concealing in his food. His call is transferred to a mental health nurse, who establishes KR’s mental capacity and with his consent is able to access his electronic summary care record and confirm his history of schizophrenia and usual medication list. The nurse also establishes that KR has not been to a GP for a prescription of his medication for some time, and has lost contact with specialist mental health services. The nurse provides advice to KR regarding his presenting minor illness, and with his consent is able to refer him directly to the local mental health crisis home treatment team. He is seen by the crisis team that afternoon, and is restarted on his medication, which has been dispensed by his GP pharmacy. The crisis home treatment team see him daily for 2 weeks, help him register with a practice and allocate a new accountable care coordinator. This CPN arranges to review him regularly, and his symptoms improve over the next few weeks. The prompt involvement of mental health services through a direct referral pathway means that KR’s mental health issues are addressed swiftly, and this prevents him from deteriorating to a point where an acute mental hospital admission is required. 19