Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England

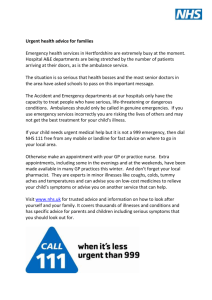

advertisement