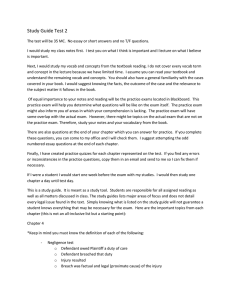

T P C S

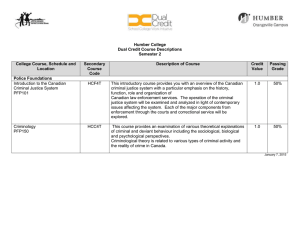

advertisement