February 2006

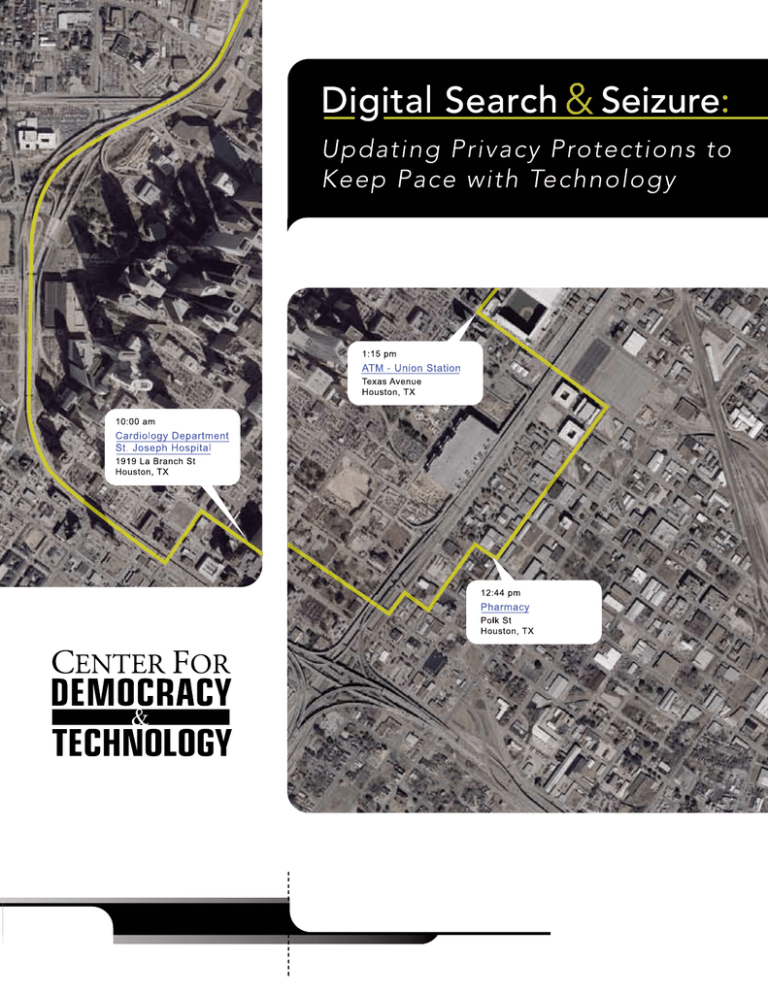

advertisement