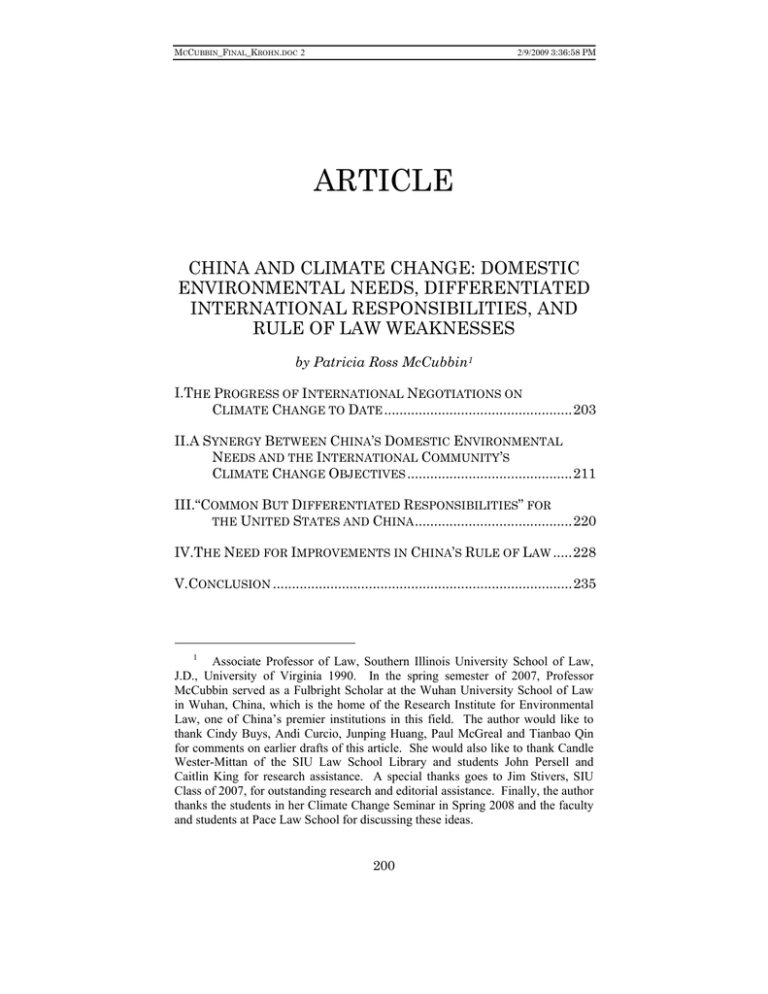

ARTICLE

advertisement