ARTICLE WIND ENERGY: SITING CONTROVERSIES AND RIGHTS IN WIND

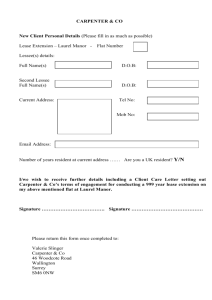

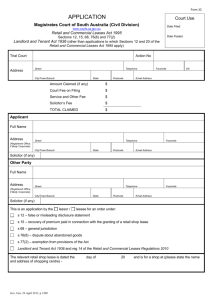

advertisement