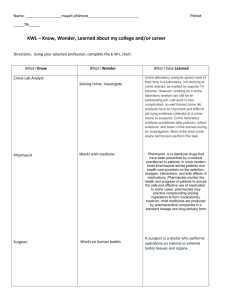

SELECTING THE BEST ANALYST FOR THE JOB A Model Crime Analyst

advertisement