Supreme Court of the United States

advertisement

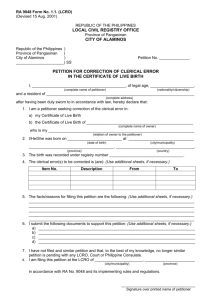

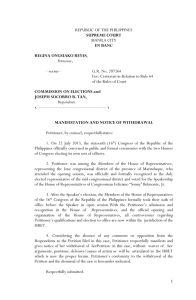

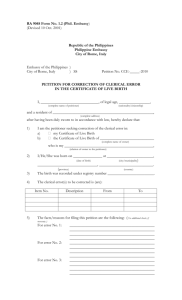

No. 15-1359 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________ EMMALINE BORNE, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. _________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourteenth Circuit _________ BRIEF OF RESPONDENT _________ November 23, 2015 Team 65 Counsel for Respondent QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether a person can be charged under 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) for making an explosive device by designing and fabricating firearm parts on a 3D printer? 2. Whether a person can be prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) for making plans to meet an individual of a known foreign terrorist organization in order to show and demonstrate potentially dangerous computer code to that individual? 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ........................................................................................ 5 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................................................................. 5 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................................................................................ 7 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................................ 11 I. THE PETITIONER’S CONVICTION FOR POSSESSING A “DESTRUCTIVE DEVICE” UNDER 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) WAS PROPER .................................................. 11 A. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) Is A Public Welfare Provision And Should Be Interpreted Broadly To Eliminate The Threat Destructive Devices Pose. ..................... 11 1. Unassembled Components Constitute a Destructive Device Under 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). ............................................................................................................ 16 2. When Considering The Cylinder and Propellants, Along With the Surrounding Circumstances of The Arrest, The Components Constitute A Destructive Device. ... 17 3. Applying A Subjective Standard, The Cylinder And Propellants Officer Smith Retrieved From Petitioner Constitute A “Destructive Device.”................................... 21 4. Both conspiracy and aiding and abetting theories attribute all components of the devices to each Petitioner. ............................................................................................. 23 II. PETITIONER’S CONVICTION FOR ATTEMPTING TO PROVIDE MATERIAL SUPPORT TO A FOREIGN TERRORIST ORGANIZATION UNDER 18 U.S.C. § 2339B WAS PROPER. ...................................................................................................................... 24 A. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B Is Not Unconstitutionally Vague Under The Fifth Amendment. 25 B. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) Does Not Violate The First Amendment. ....................... 26 1. As This Court Correctly Decided In Holder, 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) Is Not Unconstitutionally Overbroad. ...................................................................................... 26 2. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) Is Not Unconstitutional As Applied To Petitioner Because The Computer Code At Issue Is “Functional” Rather Than “Expressive” Speech Warranting A Lesser Degree of First Amendment Protection. ...................... 28 C. Petitioner’s Conviction Under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) For Attempting To Provide “Material Support” to a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” Was Proper. ........................ 29 1. For The Purposes of 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012), Clive Allen Is A Representative Of The Dixie Millions Foreign Terrorist Organization. ............................................... 29 2. Petitioner’s Actions Constituted A Clear Attempt to Provide Material Support To A Foreign Terrorist Organization. ................................................................................ 32 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................ 33 2 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1 (2010) .......................... 25, 26, 27, 28 Limtiaco v. Camacho, 549 U.S. 483 (2007) .................................................................. 11 Liparota v. United States, 471 U.S. 419 (1985) ..................................................... 11, 12 Staples v. United States, 511 U.S. 600 (1994) ..................................................... passim United States v. Berres, 777 F.3d 1083 (10th Cir. 2015) ............................................. 16 United States v. Copus, 93 F.3d 269 (7th Cir. 1996) ................................................... 14 United States v. Davis, 313 F.Supp. 710 (D. Conn. 1970)........................................... 16 United States v. Farhane, 634 F.3d 127 (2d Cir. 2011) ............................................... 26 United States v. Fredman, 833 F.2d 837 (9th Cir. 1987) ............................................ 14 United States v. Freed, 401 U.S. 601 (1971) ................................................................ 13 United States v. Greer, 588 F.2d 1151 (6th Cir. 1978) ................................................ 16 United States v. Hammond, 371 F.3d 776 (11th Cir. 2004).................................. 21, 22 United States v. Johnson, 152 F.3d 618 (7th Cir. 1998) ................................. 17, 21, 23 United States v. Kircus, 610 Fed. Appx. 936 (11th Cir. 2015) .................................... 18 United States v. Langan, 263 F.3d 613 (6th Cir. 2001) ........................................ 18, 20 United States v. Levenite, 277 F.3d 454 (4th Cir. 2002).............................................. 18 United States v. Markley, 567 F.2d 523 (1st Cir. 1977) .............................................. 14 United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) ............................................................ 27 United States v. Oba, 448 F.2d 892 (9th Cir. 1971) .............................................. 20, 21 United States v. Posnjak, 457 F.2d 1110 (2d Cir. 1972).............................................. 18 United States v. Resendez-Ponce, 549 U.S. 102 (2007)................................................ 31 United States v. Simmons, 83 F.3d 686 (4th Cir. 1996). ....................................... 16, 23 United States v. Spoerke, 568 F.3d 1236 (11th Cir. 2009) .......................................... 20 United States v. Tankersley, 492 F.2d 962 (6th Cir. 1974 .......................................... 16 United States v. Tucker, 376 F.3d 236 (4th Cir. 2004) ................................................ 18 United States v. Williams, 535 U.S. 285 (2008) .......................................................... 25 United States v. Wilson, 546 F.2d 1175 (5th Cir. 1977) ........................................ 17, 19 Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Corley, 273 F.3d 429 (2d Cir. 2001) ........................... 27 Virginia v. Hicks, 539 U.S. 113 (2003) ......................................................................... 26 Statutes 18 U.S.C. § 2339A(b) (2012) ......................................................................................... 24 18 U.S.C. § 2339B(a)(1) (2012) ..................................................................................... 24 2 11 26 U.S.C. § 5845(b) ....................................................................................................... 15 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(1) .................................................................................................... 11 3 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) ................................................................................ passim 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) (2012) .............................................................................................. 4 National Firearms Act, 26 U.S.C. § 5841-5849 (2012) ................................................ 11 Other Authorities 142 Cong. Rec. 3464 (Apr. 17, 1996) (statement of Sen. Brown). ............................... 30 Hazardous Materials Carried by Airline Passengers and Crewmembers (December 6, 2013), http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ash/ash_programs/hazm at/media/materialscarriedbypassengersandcrew.pdf. ............................................. 20 Kristen A. Nardolillo, Note, Dangerous Minds: The National Firearms Act and Determining Culpability For Making and Possessing Destructive Devices, 42 Rutgers L.J. 511, 532–536 (2011) ..................................................................... 7, 8, 17 Model Penal Code § 5.01 ............................................................................................... 31 The Islamic State (Full Length), VICE News (Dec. 26, 2014), https://news.vice.com/video/the-islamic-state-full-length........................................ 26 4 JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on October 1, 2015. R. at 2. The petition for a writ of certiorari was filed in October, during the 2015 term, and was set down for argument on January 28, 2016. R. at 1. The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) (2012). STATEMENT OF THE CASE Petitioner Emmaline Borne and accomplices Fiona and Hershel Triton were arrested on June 4, 2012. R. at 15–17. The Petitioner’s arrest resulted from a traffic stop conducted by Officer Smith of the Harrisburg Police, who pulled Mr. Triton’s vehicle over while on the way to the airport. Id. at 14–15. Mr. Triton informed Officer Smith that he was bringing the two women to the airport for a flight to Azran, where they would participate in an advanced study abroad program. Id. Officer Smith arrested Mr. Triton after a routine check revealed an outstanding arrest warrant for Mr. Triton. Id. at 14. Officer Smith remained next to Mr. Triton’s vehicle, while he waited for Mrs. Triton to pick up the two girls. Id. at 15. It was at this time that Officer Smith observed a notification appear on Petitioner’s cell phone, which read, “Meet Clive Allen at cafe.” Id. Officer Smith had received a brief from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) the previous week alerting law enforcement officers that Clive Allen, a wanted member of the “Dixie Millions” foreign terrorist organization known to be living in Azran, was suspected to have an accomplice in the Harrisburg area. Id. Officer Smith mirandized Ms. Borne and Ms. Triton upon their arrest. Id. at 15. The Harrisburg Police escorted everyone to the local police station and holding 5 facility. Id. at 16. After obtaining the necessary search warrants, multiple officers searched Mr. Triton’s vehicle and the girls’ luggage and persons. Id. In the Petitioner’s luggage, the officers found a 3D-printed plastic cylinder, a bottle of hairspray, and matches. Id. The luggage also contained a USB drive containing code that would instruct a 3D printer to print a perfect cylinder, a spreadsheet documenting recent sightings of Clive Allen, and a computer-generated image of Clive Allen. Id. In Ms. Triton’s luggage, officers also found a USB drive containing the formula for a plastic filament designed to be 3D-printed into a cylinder that could function as a gun barrel. Id. In the car’s stereo, they found a USB drive with plans for a 3D-printed gun hidden among music files. Id. On the advice of counsel, Mr. Triton and Ms. Triton agreed to cooperate by turning over all of the information they had against the Petitioner, Clive Allen, and Adalida Ascot, a teacher who had recruited the women to their Azranian study abroad program and was a suspected member of Dixie Millions. Id. At trial in the District Court for the Central District of New Tejas, FBI agents demonstrated that Petitioner’s online activity included attempts to contact members of Dixie Millions and other hacker groups. Id. at 17. The prosecution also established that the Petitioner had shared numerous sympathetic articles about the Dixie-Millions. Id. at 18. Petitioner had also recently posted the message, “With one wish, I wish all guns would blow up. #guncontrol,” on her Twitter. Id. In addition to the evidence regarding Petitioner’s online activity, the prosecution submitted FBI ballistic expert testimony that the plans on the two USB 6 drives could be combined to create a gun. Id. The ballistic expert testified that any gun produced using this method would explode upon firing, but a “bright teenager” could convert the cylinder, hairspray, and matches in Petitioner’s luggage into a pipe bomb with instructions available online. Id. The jury determined that the combination of parts seized by law enforcement constituted a “destructive device” under 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) and sentenced Petitioner to twelve years in prison. Id. The jury also convicted her of attempting to provide material support to a foreign terrorist organization under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B and sentenced her to fifteen years in prison, with the terms to be served concurrently. Id. The Fourteenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed both convictions. Id. at 24. The court looked both to the readiness with which Petitioner could assemble a pipe bomb from the component parts in her luggage and her previous statements in support of terrorist activity and exploding guns to conclude that she had made a pipe bomb constituting a destructive device. Id. at 18–24. SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT Title 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) defines a “destructive device” as “any combination of parts either designed or intended for use in converting any device into a destructive device as defined in subparagraphs (1) and (2) and from which a destructive device may be readily assembled.” 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). Subparagraphs (1) and (2), in turn, list several types of weapons whose unregistered possession or transmission in interstate commerce is proscribed elsewhere in the statute. Id. 7 This statute creates a regulatory offense designed to reduce the harm that destructive devices pose to the public. These offenses tend to require the prosecution to prove a lower mens rea than in equivalent general criminal offenses. Staples v. United States, 511 U.S. 600, 619 (1994). The statutory language of 26 U.S.C. 5845(f)(3) (2012) regarding design and intent establishes a lower evidentiary burden on the government. Id. Under this burden, the government is not required to prove a defendant’s intention to use the device as a weapon if it can establish that the device in question was designed to operate as a weapon covered by the act. Id. Case law applies three general approaches to determining whether a device or combination of parts constitutes a destructive device under subpart (3). Kristen A. Nardolillo, Note, Dangerous Minds: The National Firearms Act and Determining Culpability For Making and Possessing Destructive Devices, 42 Rutgers L.J. 511, 532– 536 (2011). The first approach, an objective analysis, considers the overt nature of the object. The object is considered a “destructive device” if the only reasonable use for the object is as a device described in 26 U.S.C. 5845(f). Id. at 534. The second approach first considers an object’s reasonable uses before exploring circumstances surrounding a defendant's’ arrest. Id. Under this second analysis if the device has multiple possible uses, at least one of which is destructive, the reviewing body then considers the surrounding circumstances for evidence of which use of the device was most likely. Finally, a subjective approach looks to a defendant’s intended use of the device in order to determine whether the device constitutes a “destructive device” under the statute. Id. at 535–36. 8 The cylinder, hairspray, and matches recovered from Petitioner’s luggage are a destructive device as defined by the statute. An objective analysis shows no social use for these parts as combined, but their proximity allows the inference that they were to be joined and converted into a pipe bomb. A mixed standard analysis, if it gives weight to the inclusion of social items as part of the device, would look to the surrounding circumstances and find the other weapons-related items recovered from the car and Petitioner’s history of endorsing terrorist activity as evidence that the device was designed or intended for use as a weapon. A subjective standard, though disfavored, would look at the same evidence and conclude that Petitioner intended to convert the parts into a pipe bomb covered by the statute. The Petitioner can also be criminally liable for the items recovered from Mr. and Ms. Triton through an aiding and abetting theory or a theory of conspiracy. Their USB drives contained a design for a 3D-printed gun and a formula for plastic filament that, if used together, produce a 3D-printed gun that FBI experts demonstrated at trial would explode upon firing. The two USB drives together constitute a destructive device that can be readily converted into a bomb. An objective analysis shows the only plausible use is as a weapon, and a mixed or subjective standard would look at the surrounding evidence, including the parts of the other unassembled bomb found in the car and Petitioner’s online activity, including a tweet expressing a wish that all the world’s guns “blow up.” The Petitioner was also convicted of attempting to provide material support to a foreign terrorist organization under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012). She was arrested with 9 documented plans to meet a confessed leader of the terrorist group Dixie Millions and tangible items to give him, which constitute material support. The statute is not unconstitutionally vague as applied to the Petitioner. Petitioner’s conduct falls squarely within the contemplation of the language of § 2339B. Nor is §2339B unconstitutionally overbroad. This Court held as much in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1 (2010) and there is no reason to depart from that holding here. While the statute does restrict some speech, it also does not penalize mere affiliation with a Foreign Terrorist Organization. The statute is also not unconstitutional as applied to Petitioner. Because the computer code that Petitioner intended to give Clive Allen is “functional” as opposed to “expressive” speech, this Court need apply only intermediate scrutiny. Under this level of scrutiny, the statute’s prohibition of Petitioner’s transfer of “tangible property” that could be used to manufacture weapons to a Foreign Terrorist Organization is narrowly tailored to the substantial government interest in preventing terrorists from gaining access to dangerous resources. Finally, the statute would survive even strict scrutiny because the government’s interest in restricting speech here is just as compelling as it was in Holder. Finally, Petitioner was properly convicted under § 2339B for her attempt to provide material support to a Foreign Terrorist Organization by delivering dangerous computer code to Clive Allen. By attempting to deliver the USB to Clive Allen, an undisputed member and the face of the terrorist organization Dixie Millions, Petitioner attempted to provide that organization with material support. § 2339B 10 rightly does not distinguish providing material support to a Foreign Terrorist Organization and providing that same support to the de facto head of that organization. Petitioner’s actions also demonstrate all the elements of attempting to provide material support, which § 2339B expressly prohibits. Petitioner made detailed plans to meet with Clive Allen and likely would have succeeded in delivering the USB to him had she not been stopped on her way to the airport. ARGUMENT I. THE PETITIONER’S CONVICTION FOR POSSESSING A “DESTRUCTIVE DEVICE” UNDER 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) WAS PROPER A. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) Is A Public Welfare Provision And Should Be Interpreted Broadly To Eliminate The Threat Destructive Devices Pose. The question presented to the Court is whether an individual found in possession of the ingredients to create a pipe bomb was properly convicted under the National Firearms Act, for possessing a “destructive device”. R. at 1. Given that this issue is one of statutory interpretation, the analysis begins with the text of the statute. Limtiaco v. Camacho, 549 U.S. 483, 488 (2007) (“As always, we begin with the text of the statute.”) Title 26, section 5845(f) of the United States Code defines “destructive devices” for numerous federal statutes. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). Possession and transmission in interstate commerce of a “destructive device” is regulated and restricted by the National Firearms Act (“NFA”). National Firearms Act, 26 U.S.C. § 11 5841-5849 (2012). The definition of “destructive devices” in section 5845(f) is subdivided into three parts. whose possession and transmission in interstate commerce the statute regulates. Subparts (1) and (2) cover particular types of weapons, including bombs, grenades, and missiles, as well as particular projectiles that are less easily classified. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(1)–(2) (2012). Subpart (3), which is most relevant to this case, extends coverage to, “any combination of parts either designed or intended for use in converting any device into a destructive device as defined in subparagraphs (1) and (2) and from which a destructive device may be readily assembled.” 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). Parts of the NFA establish general criminal offenses, such as the ban on possessing unregistered machine guns, which includes as an element the knowledge that the weapon possessed was not just a firearm but an automatic firearm. Staples, 511 U.S. at 619. However, other offenses, including those concerned with “destructive devices,” are “public welfare” offenses. Liparota v. United States, 471 U.S. 419, 433 (1985). Public welfare (or regulatory) offenses prohibit “conduct that a reasonable person should know is subject to stringent public regulation and may seriously threaten the community's health or safety.” Id. These offenses regulate “potentially harmful or injurious items” whose obvious danger so outweighs their social utility that the legislature creates prophylactic offenses to control them before they can cause harm. Staples, 511 U.S. at 607. Whether a statute proscribes a general crime or regulatory offense is often a matter of statutory interpretation, with the designation determining the mens rea 12 necessary to establish an element of the offense where a statute is silent. For example, the Supreme Court in Staples v. United States rejected the government’s argument that the section of the National Firearms Act banning possession of a machine gun in interstate commerce constituted a public welfare offense. Id. at 606– 618. The United States contended that because machine guns are inherently dangerous and the large number of gun laws should alert a reasonable person that his weapon is likely subject to regulation, the provision prohibiting their possession was regulatory. Accordingly, the government would not be required to prove the Petitioner knew the firearm in his possession was a machine gun. Id. at 606–609. The Court rejected the government’s argument, noting three reasons for requiring proof that a Petitioner knows her weapon has the qualities that bring it within the ambit of the NFA. First, though firearms might be more dangerous than some of the items and activities covered by other public welfare offenses, they are ubiquitous. Id. at 610–612. Given the prevalence of firearms in society, the risk of criminalizing such a common possession without knowledge of a specific feature – such as automatic firing –that made possession an offense was too high. Id. Second, heavy regulation is insufficient to give notice of a regulatory offense. Id. at 614. Third, the Court noted that most strict liability regulations come with smaller penalties, while the convicted offense was a felony potentially carrying a ten-year prison sentence that the Court considered high for a strict liability offense. Id. at 616–618. Section 5845(f)(3) exhibits the qualities of a public welfare offense without the distinguishing factors the Staples court found dispositive. Unlike the machine gun 13 statute, (f)(3) regulates objects that are unlikely to be mistaken for lawful possessions. While “there is a long tradition of widespread lawful gun ownership by private individuals in this country,” there is no similar tradition of bomb, missile, or grenade ownership. Id. at 610. Possessing these and other destructive devices, as defined in subparts (1) and (2), without proper registration is unlawful because they are the sort of “potentially harmful or injurious items” that do not have enough social utility, nor is their possession prevalent enough to justify their unregulated presence in interstate commerce. Id. at 607. While machine guns cannot be prohibited due to their widespread and legitimated use, the components of the pipe bomb found in Petitioner’s luggage share neither of these characteristics. Given the lethal capabilities of “destructive devices”, as defined in of 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012), illicit possession of these items does not always carry the same mens rea requirement that the statute in Staples did. For instance, the Court held in United States v. Freed held that a Petitioner did not need to know that possession of grenades was prohibited in order to be prosecuted. 401 U.S. 601, 609 (1971) (“This is a regulatory measure in the interest of the public safety, which may well be premised on the theory that one would hardly be surprised to learn that possession of hand grenades is not an innocent act. They are highly dangerous offensive weapons. . . .”). The qualities that make grenades a regulatory concern applies to all “destructive devices”: they are not widely owned, they are extremely dangerous, and they are generally difficult to mistake for legitimate items that fall outside the statute. These 14 items are sufficiently identifiable to justify imposition of higher sentences when a Petitioner chooses to interact with them. Thus, while intent is not required by the statute, it does provide a second path to conviction. A Petitioner is culpable if her combination of parts is “either designed or intended” for conversion into a destructive device. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). If intent is evident beyond a reasonable doubt, ambiguity as to the destructive nature of the device can be resolved in favor of conviction. See United States v. Copus, 93 F.3d 269, 272 (7th Cir. 1996) (finding that a jury could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that defendant’s homemade detonators were intended to be used as weapons); United States v. Fredman, 833 F.2d 837, 839 (9th Cir. 1987) (holding that “intent to use” must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt); United States v. Markley, 567 F.2d 523, 526 (1st Cir. 1977) (holding that a jury must find beyond a reasonable doubt that the device was intended to be used as a destructive device). The higher potential sentence is thus important to allow courts adequately to deter and condemn instances in which the prohibited conduct is motivated by a “vicious will.” Staples, 511 U.S. at 617. The language of the statute also suggests a lower mens rea requirement for destructive devices than the “knowing” standard applied to machine guns. The subpart regulating machine guns covers parts or combinations of parts “designed and intended” for conversion into a machine gun. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(b) (2012) (emphasis added). In contrast, destructive devices include any combination of parts “designed or intended” for conversion into a destructive device. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) 15 (emphasis added). This distinction, within the same definitional section, suggests that a person would have to know her device was intended to be a machine gun under the former provision, but would not need to know her device was designed to be destructive under the latter. 1. Unassembled Components Constitute a Destructive Device Under 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). The fact that the propellant, fuse, and explosive housing of Petitioner’s pipe bomb were unassembled at the time of Officer Smith’s search does not prevent a determination that they constitute a single destructive device. The language of section 5845(f)(3) compels the conclusion that the parts of an unassembled device can constitute a “destructive device.” The statute refers to “any combination of parts… from which a destructive device may be readily assembled,” in its definition of “destructive device”. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012). The language itself indicates that the statute’s framers intended that the statutes’ regulations apply similarly to unassembled parts that, when combined, can be converted from a benign state to a dangerous one. Given the variability of ingredients in potential destructive devices, numerous circuit and district courts have applied this principle of “ready assemblage” to numerous situations. In United States v. Tankersley, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed conviction of a Petitioner in whose camper police found “an M-80 firecracker encased in an envelope, some fuse, twine, and a can of paint and varnish remover.” 492 F.2d 962, 965 (6th Cir. 1974). The court held that the district court did not err in permitting the jury to infer that the Petitioner intended to convert these 16 items, each with legitimate uses in isolation, into a bomb. Id. at 966–967. See also United States v. Greer, 588 F.2d 1151, 1157 (6th Cir. 1978) (upholding conviction under 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) for possessing explosives and blasting caps that had not been assembled); United States v. Berres, 777 F.3d 1083, 1087 (10th Cir. 2015) (upholding conviction for possessing a bag containing a flash bang device, black powder, fuse and matches); United States v. Davis, 313 F.Supp. 710, 711 (D. Conn. 1970) (affirming conviction despite none of the device’s components being assembled together). Similarly, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals has held that the components of a Molotov cocktail could qualify as a “destructive device”, even if there is no identifiable fuse in the immediate proximity. United States v. Simmons, 83 F.3d 686, 688 (4th Cir. 1996). 2. When Considering The Cylinder and Propellants, Along With the Surrounding Circumstances of The Arrest, The Components Constitute A Destructive Device. Circuits are split on the issue of which standard to apply in determining whether an object constitutes a “destructive device” contemplated by § 5845(f)(3). The objective, subjective, and “mixed standards” that have been proffered each have advantages, but the mixed standard is the most consonant with the statute’s public safety function. Kristen A. Nardolillo, Note, Dangerous Minds: The National Firearms Act and Determining Culpability For Making and Possessing Destructive Devices, 42 Rutgers L.J. 511, 532–536 (2011). The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals described the mixed standard test in United States v. Johnson: If the objective design of the device or component parts indicates that the object may only be used as a weapon, i.e., for no legitimate social or 17 commercial purpose, then the inquiry is at an end and subjective intent is not relevant. However, if the objective design inquiry is not dispositive because the assembled device or unassembled parts may form an object with both a legitimate and an illegitimate use, then subjective intent is an appropriate consideration in determining whether the device or parts at issue constitute a destructive device under subpart (3). 152 F.3d 618, 628 (7th Cir. 1998).The first prong of the mixed standard is also the only prong of the objective standard, which looks to the objective nature of the device in question. A court using this standard applies strict liability to Petitioners whose weapons can only reasonably be considered components of destructive devices as defined in subparts (1) and (2) and exonerating those whose devices have a clearly benign use. Nardolillo, supra, at 523–527. The presence of innocuous items does not automatically eliminate the inference that their combination into a single device would be covered by the statute. See, e.g., United States v. Wilson, 546 F.2d 1175, 1177 (5th Cir. 1977) (“[W]hile gasoline, bottles and rags all may be legally possessed, their combination into the type of home-made incendiary bomb commonly known as a Molotov cocktail creates a destructive device.”); United States v. Kircus, 610 Fed. Appx. 936, 936–37 (11th Cir. 2015) (per curiam) (affirming conviction for possessing a destructive device consisting of a modified airbag cylinder). But cf. United States v. Tucker, 376 F.3d 236, 238–39 (4th Cir. 2004) (affirming conviction for conspiracy to make a destructive device based on evidence that the Petitioner had purchased most of the component parts required to build a pipe bomb). Congress never intended to provide an end run around coverage for anyone who used a commercial product as a component of an otherwise destructive device. United States v. Levenite, 277 F.3d 454, 467–68 (4th Cir. 2002) (affirming 18 district court holding that while detonators could serve legitimate purposes, the circumstances surrounding a defendant’s arrest justified the conclusion that the detonators constituted "destructive device”). The close vicinity of a potential propellant and fuse to a unique, homemade bomb casing leave no reasonable doubt that the cylinder is designed to be converted into the type of bomb contemplated by subpart (f)(3). United States v. Langan, 263 F.3d 613, 625 (6th Cir. 2001) (“To qualify under the statute, we do not require that the destructive device operate as intended. It is sufficient for the government to show that the device was ‘readily convertible’ to a destructive device.”). In cases deciding that a component with a potentially legitimate use destroyed liability under subpart (f)(3), the nexus between the device and its benign use has been evident. E.g. Levenite, 277 F.3d at 467–68. United States v. Posnjak, 457 F.2d 1110, 1119 (2d Cir. 1972) (“The language implies at minimum the presence of parts ‘intended’ to ‘convert’ any ‘device’ into a destructive device akin to those referred to in § 5845(f) (1) and (2), all of which have definite non-industrial characters.”). Still, the presence of components with legitimate uses does put tension on more formalist interpretations of the objective test. The more a legitimate object seems at odds with an apparent but difficult-to-prove intent to combine parts into a destructive device. Here, Petitioner’s device had an essential component with no such clearly benign use; if not a bomb, the cylinder would have been an essential component of an unregistered firearm that Petitioner’s accomplice has stated he intended to enter into commerce, meaning that unlike dynamite or grenade, the cylinder does not have any 19 clearly legitimate use. R. at 15. A mixed standard or objective standard analysis, then, would find Petitioner’s device a “destructive device” covered by (f)(3). Though both the objective and mixed standards should end the analysis there, the mixed standard is preferable because its second prong can deflect error in the first prong analysis. If the court were to determine the bomb housing, matches, and hairspray might have legitimate uses, it would weigh additional factors to determine whether the device was designed or intended for destructive purposes. See United States v. Wilson, 546 F.2d 1175, 1176 (5th Cir. 1977) (relying on government testimony to establish that the explosive device was not “commercial dynamite”). It would consider expert testimony, which in the present case suggests the plastic cylinder would explode any time it was configured as a gun and fired a bullet and that a bright teenager such as the Petitioner could convert the cylinder into a bomb using the items found in the Petitioner and her accomplice’s luggage with instructions available on the internet. R. at 18. The close proximity of the components needed to turn the cylinder into a bomb also suggests their location was not fortuitous. Matches and hairspray are cheap, readily available products that are likely to be confiscated or at least raise suspicions at airport security. See Hazardous Materials Carried by Airline Passengers and Crewmembers (December 6, 2013), http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ash/ash_programs/hazmat/ media/materialscarriedbypassengersandcrew.pdf. That Petitioner would bring these to the airport instead of buying them duty-free or upon landing, and in the same luggage as the explosive casing, suggests a particular desire not to risk going without 20 one of these components, or possibly even to assemble the device on the way to the airport. Because separated components may constitute a destructive device, some courts have asked how readily parts could be assembled into such a device. Langan, 263 F.3d at 625 (holding that the government need only show that the device be capable of exploding or be readily made to explode, even if it key components are not present). This inquiry also points toward conviction, as the cylinder was recovered with a program capable of mass-producing identical devices within hours. All of these factors indicate that the cylinder was designed to be part of a destructive device. 3. Applying A Subjective Standard, The Cylinder And Propellants Officer Smith Retrieved From Petitioner Constitute A “Destructive Device.” The Ninth and Eleventh Circuits have applied a subjective analysis, finding a Petitioner’s subjective intent dispositive in determining (f)(3) liability. United States v. Oba, 448 F.2d 892 (9th Cir. 1971); United States v. Spoerke, 568 F.3d 1236, 1243 (11th Cir. 2009). This standard gets some textual legitimacy from the fact that subpart (f)(3) includes the only reference to intent. 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) (“[A]ny combination of parts either designed or intended for use in converting any device into a destructive device.”). However, the text indicates culpability when the device is “designed or intended,” meaning there must be room for conviction based on the objective design of the device. Id. See Johnson, 152 F.3d at 625 (emphasizing the difference between an item that was “designed” and one that was “intended” to serve as a “destructive device”). 21 A subjective standard also undermines § 5845(f)’s function as a public welfare statute. Emphasizing the Petitioner’s mens rea de-emphasizes the goal of regulating the items whose use causes harm to the public. An intent-based standard would remove opportunities to deter the proliferation of destructive devices any time a Petitioner does not clearly demonstrate an intent to use the device in a malicious way, despite the generally reduced standards for regulatory offenses and the statutory text designating design and intent as separate paths to conviction. The cases convicting Petitioners under this subjective standard are exceptional. United States v. Oba concerned a Petitioner who had pled guilty to unlawfully making and transferring a destructive device. 448 F.2d at 893. Based on the guilty plea, the court found clear intent and saw no reason to look further to affirm the conviction. Acquittals demonstrate how these dangerous items can remain in public because of the difficulty of proving intent. The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in United States v. Hammond, upheld an acquittal of a Petitioner indicted for possession of a cardboard tube filled with explosive powder. 371 F.3d 776, 778 (11th Cir. 2004). The court found that the government had failed to offer any evidence that the device was designed as a weapon besides the fact that it would explode. Id. Despite these concerns, the evidence introduced in this case still supports conviction under a subjective analysis. Petitioner was arrested with the components of a pipe bomb in her luggage while en route to an airport. She and her accomplices also had two USB drives containing programs that could produce identical weapons. Petitioner’s online activity also supports a finding of intent to possess a destructive 22 device. She posted a tweet expressing a wish that “all guns would blow up,” which is exactly what the 3D-printed-gun–based cylinder would do, and she was arrested with evidence of plans to meet with a wanted terrorist. R. at 15. Petitioner does not concede an intent to use a destructive device, but this has never been the threshold necessary to convict on an intent standard. 4. Both conspiracy and aiding and abetting theories attribute all components of the devices to each Petitioner. In addition to the pipe bomb seized from Petitioner’s luggage, the Court of Appeals also held that the 3D-printed gun design and filament formula constitute a destructive device. Anyone with access to a 3D printer and those USB drives would only need to press a button and wait a few hours to produce a handgun that would explode upon any attempt to shoot. Both Tritons took plea deals, acknowledging some degree of criminal culpability. R. at 15. Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 2 (2012), Petitioner may be punished as a principal for aiding or abetting the guilty parties’ activities related to the items they unlawfully possessed at the time of their arrest. Alternatively, Petitioner’s liability might attach on a theory of conspiracy. All three individuals worked with the filaments, 3D-printed gun design, and the code that produced the plastic cylinder. R. 6, 15. They attempted to bring these items to the airport and even tried to conceal the gun design amid music files on one of the USB drives. R. at 15. A jury could reasonably infer the existence of a conspiracy to commit the crime to which the Tritons pled and of which Petitioner was convicted. With both theories attributing the gun design USB drive and filament formula USB drive to Petitioner, the question becomes whether those items constitute a 23 destructive device. At trial, FBI ballistics experts testified that a gun printed using the design and formula recovered from Petitioner would explode every time it fired a round. R. at 18. Though explosiveness is not dispositive of destructiveness, the design is unambiguously a weapon. As the Court of Appeals noted, the two USB drives together are a combination of parts under subpart (3) that are designed to be converted into a bomb under subpart (1). Id. This device, like the pipe bomb found in Petitioner’s possession, is a destructive device under any of the three standards of review. An objective analysis would find that it is designed to explode in a user’s hands. See R. at 21. Whether that is its intention or not is irrelevant under this standard. Poor craftsmanship also does not have any bearing on the analysis when a device has the effect of causing damage in the manner of a destructive device as defined under subpart (1) or (2). Simmons, 83 F.3d at 687 . A mixed standard would note the ease with which the conversion occurs and the fact that it only takes a few hours. See Johnson 152 F.3d at 628. Also relevant to a mixed or subjective standard are Petitioner’s statements, introduced at trial, about her desire to see all guns explode. R. at 18. The presence of either device’s components together en route to an airport, with a clear purpose to meet a wanted terrorist abroad, are more than enough to lead a reasonable jury to find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. II. PETITIONER’S CONVICTION FOR ATTEMPTING TO PROVIDE MATERIAL SUPPORT TO A FOREIGN TERRORIST ORGANIZATION UNDER 18 U.S.C. § 2339B WAS PROPER. 24 A. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B Is Not Unconstitutionally Vague Under The Fifth Amendment. Title 18 U.S.C. § 2339B outlaws knowingly providing, or attempting or conspiring to provide, material support or resources to a foreign terrorist organization (Foreign Terrorist Organization). To violate the section, a person must know the organization is a Foreign Terrorist Organization or that it has engaged in terrorist activity. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B(a)(1) (2012). Section 2339A defines “material support or resources” as “any property, tangible or intangible, or service, including … training, expert advice or assistance, … weapons, lethal substances, explosives, [or] personnel (1 or more individuals who may be or include oneself).” It further defines “training” as “ instruction or teaching designed to impart a specific skill” and defines “expert advice or assistance” as “advice or assistance derived from scientific, technical or other specialized knowledge.” 18 U.S.C. § 2339A(b) (2012). In Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, the Supreme Court rejected a claim that these provisions are unconstitutionally vague as applied to conduct far more tenuously connected to terrorist activity than the convicted conduct in the present case. 561 U.S. 1, 20–21 (2010). The plaintiffs in Holder sought to train members of two Foreign Terrorist Organizations in legal skills that the groups could apply in resolving conflicts through international law instead of resorting to violence. Id. at 14–15. Rejecting a Fifth Amendment Due Process claim, the Court found the statutory language sufficiently narrow to give the Petitioners notice that their conduct was proscribed. Id. at 20–21. 25 In contrast, there can be little doubt that the conduct in the present case is prohibited by the statute. Petitioner attempted to deliver a program with instructions that could be used to mass-produce weapons anywhere in the world. See R. at 16. She also brought a prototype of the gun barrel her program would generate through a 3D printer. R. at 18. The attempt to deliver this tangible good, and the likely training to use it, fits squarely within the statute’s unambiguous contemplation. This means that, regardless of whether the conduct takes the form of speech, Petitioner has no standing to complain about vagueness as applied to others. Id. at 20 (citation omitted). B. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) Does Not Violate The First Amendment. 1. As This Court Correctly Decided In Holder, 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) Is Not Unconstitutionally Overbroad. Overbreadth doctrine is “strong medicine” that courts employ only with careful consideration. United States v. Williams, 535 U.S. 285, 293 (2008). Additionally, Petitioner “bears the burden of demonstrating, from the text of the law and from actual fact, that substantial overbreadth exists.” Virginia v. Hicks, 539 U.S. 113, 122 (2003) (internal quotation marks omitted) (citation omitted). Section 2339B is not so overbroad as to chill a substantial amount of clearly protected First Amendment activity. The statute targets material support for Foreign Terrorist Organizations, only a small amount of which is expressive activity. Of the expressive activity that the statute reaches, all of it either directly facilitates the goals of Foreign Terrorist Organizations or at least frees resources that Foreign Terrorist Organizations might 26 potentially use toward those goals. United States v. Farhane, 634 F.3d 127, 137 (2d Cir. 2011) (“[T]he statute is carefully drawn to cover only a narrow category of speech to, under the direction of, or in coordination with foreign groups that the speaker knows to be terrorist organizations.”) (citing Holder, 130 S. Ct. at 2723). “Such circumstances do not evidence overbreadth.” Id. As this Court in Holder pointed out, “[s]ection 2339B does not criminalize mere membership in a designated foreign terrorist organization. It instead prohibits providing “material support” to such a group.” 561 U.S. at 18. Barring some other statute or regulation, membership in or communication with Dixie Millions is lawful. “Mere association” and correspondence are robustly protected by the First Amendment. The Justice Department’s efforts to enforce § 2339B have done nothing to interfere with reporters embedding with Foreign Terrorist Organizations or private individuals advocating on behalf of Foreign Terrorist Organizations. See The Islamic State (Full Length), VICE News (Dec. 26, 2014), https://news.vice.com/video/the-islamic-state-full-length (documenting a reporter’s experience embedded with a Foreign Terrorist Organization, which did not result in prosecution of the reporter by the United States). The statute is narrowly tailored so that it only applies when affiliation takes the form of material support. It “does not penalize mere association with a foreign terrorist organization.... What [it] prohibits is the act of giving material support . . . . [The] decisions scrutinizing penalties on simple association or assembly are therefore inapposite.” Holder, 561 U.S. at 39. 27 2. 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) Is Not Unconstitutional As Applied To Petitioner Because The Computer Code At Issue Is “Functional” Rather Than “Expressive” Speech Warranting A Lesser Degree of First Amendment Protection. This Court in Holder decided that § 2339B imposes a content-based restriction on speech. 561 U.S. at 21. (“The First Amendment issue before us is… whether the Government may prohibit what plaintiffs want to do—provide material support to the PKK and LTTE in the form of speech.”). The Court determined that any time a Petitioner is prosecuted under § 2339B for speech activity, a court must therefore apply strict scrutiny. Id. Unlike the speech at issue in Holder, the computer code in question does not warrant the same level scrutiny. Computer code has both “functional” and “expressive” components. Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Corley, 273 F.3d 429, 451 (2d Cir. 2001) (citing Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367, 386, (1969)). The “functional” component of computer code warrants merely intermediate scrutiny under the First Amendment. Id. Under intermediate scrutiny, the United States must demonstrate that its restriction on the transfer of the devices containing this code is substantially related to an important government interest. United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 377 (1968). As outlined in Holder, the government interest in combating terrorism is not only important, but compelling enough to meet the highest tier of scrutiny. 561 U.S. at 36 (“[T]o serve the Government’s interest in preventing terrorism, it was necessary to prevent the providing of material support . . . .”). Limiting a terrorist’s access to weapons or a key component used for manufacturing weapons is substantially related to this interest. Therefore, as applied to Petitioner, § 2339B prohibits the 28 transmission of “tangible property:” a USB key that, when inserted into a 3D printer, allows it to produce weapons. It is the functional component, the ability of the code to produce a weapon when used with a 3D printer, that § 2339B targets. Thus, in upholding Petitioner’s conviction, this Court need not decide the more complex question of whether any “expressive” component of the code, assuming it has any, merits First Amendment protection. Even if this Court were to decide that the code in question is speech, the statute would still withstand strict scrutiny. Again, the Government’s interest in preventing Petitioner’s attempted speech is just as strong here as it was for the speech in Holder. Provision of weapons or components used for stealthily manufacturing weapons poses a serious threat to the United States. To the extent that § 2339B covers transfer of the code and any demonstration of its use that Petitioner may have hoped to provide, the statute is a lawful restriction of speech under the First Amendment. C. Petitioner’s Conviction Under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012) For Attempting To Provide “Material Support” to a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” Was Proper. 1. For The Purposes of 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012), Clive Allen Is A Representative Of The Dixie Millions Foreign Terrorist Organization. No party contests Dixie Millions’ designation as a foreign terrorist organization. Clive Allen is a confessed half of the duo, the “Millions” of Dixie Millions, who released millions of classified documents stolen from the National Security Agency in an attempt to pressure the government into making policy changes. R. at 5. Though he announced his retirement from the group in a video 29 released in 2012, R. at 6, the United States does not assign the declaration any legal force. An alternative view of the law would make antiterrorism laws farcical. The retirement announcement, combined with his sharing state secrets with the Azran government in order to gain asylum for his retirement, do not renounce Dixie Millions’ work by any common understanding of the word “renunciation.” The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) was intended to be a robust statute, drafted in response to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing in New York and the 1995 Alfred B. Murrah Federal Building bombing in Oklahoma City. That it would have looser requirements than the common law of criminal conspiracy is incredulous. As the Fourteenth Circuit Court of Appeals noted, hacker collectives behave differently from traditional terrorist groups in ways that require new interpretations of existing law. R. at 23. Unlike traditional Foreign Terrorist Organizations, hacker groups are geographically diffuse and organizationally decentralized. Id. at 22. Membership or representative status is likely to be more tenuous and harder to prove, as individuals may essentially freelance for any unlawful project that motivates them. Id. (“These groups thrive on their anonymity and revel in their lack of formal structures.”). Of course, it is still possible to provide material support to such a group, but that support would not be as clearly defined as the types of aid primarily contemplated by Congress: financial support to a bank account held in the name of the group or recruitment of personnel to send to terrorist training camps. Either this decentralized, informal structure is all it takes to escape American anti-terrorism 30 measures, or a person who has conducted terrorist activities on behalf of a group may be a representative of the group for the purposes of the AEDPA. Without addressing the particular problem of hackers, Congress did account for the potential evolution of terrorist organizations. While the language of the statute emphasizes the role of terrorist organizations, the provision ultimately has the “intent of punishing all persons involved, to whatever degree, in terrorist activities.” 142 Cong. Rec. 3464 (Apr. 17, 1996) (statement of Sen. Brown). Clive Allen fits squarely within that description. See 8 U.S.C. § 1182 (a)(3)(B)(v) (2012) (“As used in this paragraph, the term “representative” includes an officer, official, or spokesman of an organization, and any person who directs, counsels, commands, or induces an organization or its members to engage in terrorist activity”). Other parts of the statute also support the conclusion that material support directed at Clive Allen constitutes support for Dixie Millions under § 2339B. The provision establishing the procedures for designating and revoking designation of Foreign Terrorist Organization status is contained in the Immigration and Naturalization Act, which also includes a definition a “representative” of a Foreign Terrorist Organization. This definition includes any person who directs or induces members of an organization to engage in terrorist activity. Applying the logic of § 2339B, in which provision of oneself to a Foreign Terrorist Organization is considered provision of personnel, a person can be a representative if she is a member of a Foreign Terrorist Organization and directs or induces herself to commit a terrorist act. Absent any official channels by which a Foreign Terrorist Organization can 31 engage in transactions in its capacity as an organization, transacting with a representative who has committed terrorist acts in its name must, at the very least, constitute material support to the organization. To reverse Petitioner’s conviction would set a precedent by which Foreign Terrorist Organizations could receive as much support as they can solicit, simply by structuring themselves loosely. 2. Petitioner’s Actions Constituted A Clear Attempt to Provide Material Support To A Foreign Terrorist Organization. Section 2339B proscribes anyone from knowingly “attempt[ing] or conspir[ing]” to provide material support to a Foreign Terrorist Organization: Petitioner was arrested before she could achieve her goal, but her actions are still sufficient to constitute an attempt. There is no federal statutory definition of attempt, but federal courts have followed the approach laid out in the Model Penal Code. See United States v. Resendez-Ponce, 549 U.S. 102, 107 (2007). This formulation allows conviction for a criminal attempt if a person (a) acts with the level of culpability otherwise required for commission of the crime and (b) purposely does anything that is a substantial step toward the commission of the crime. Model Penal Code § 5.01 (Unif. Laws Annotated). Petitioner acted with knowledge of Dixie Millions’ terrorist activities, which is the level of culpability necessary for conviction. R. at 11. She also took substantial steps toward providing material support to the organization. Petitioner brought weapon-manufacturing software and a prototype of the component in her luggage, intending to meet a known terrorist abroad. R. at 16. She had a spreadsheet documenting this terrorist’s known movements and an image of his likeness to reference in trying to locate him, as well as a personal reminder on her phone to meet 32 him at a particular location. R. at 12. Having assembled all of these items and left for the airport, the only remaining step to provide material support would be to meet the terrorist and transfer the property. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, we ask this court to affirm the decision of the Fourteenth Circuit Court of Appeals to uphold Petitioner’s conviction under both 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f)(3) (2012) and 18 U.S.C. § 2339B (2012). 33