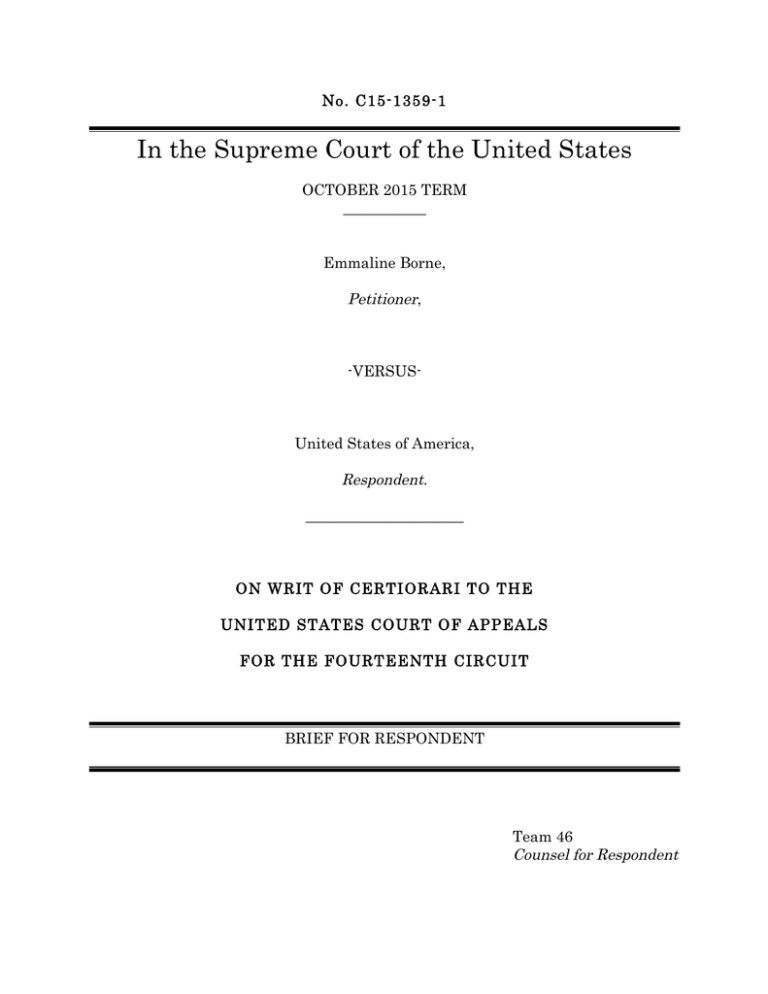

In the Supreme Court of the United States

advertisement