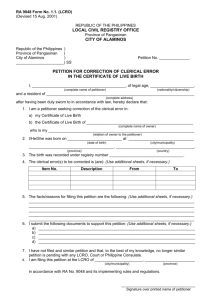

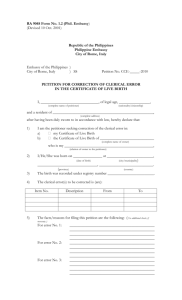

______________________________________________________________________________ No. C15-1359-1 ___________________________

advertisement