Document 10882558

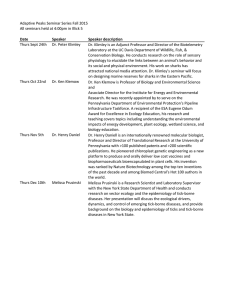

advertisement