Document 10882553

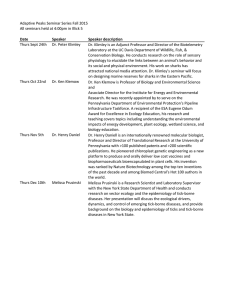

advertisement