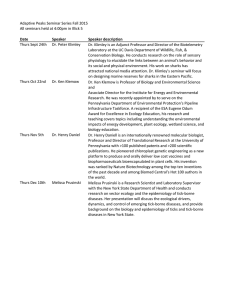

No. C15-1359-1 I

advertisement