Document 10868971

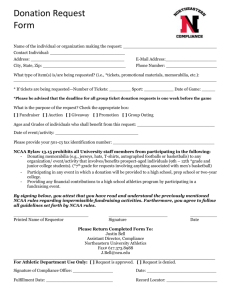

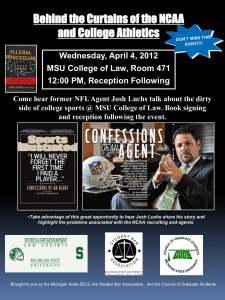

advertisement