Document 10868964

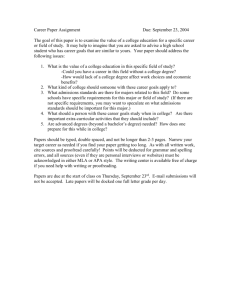

advertisement