Document 10868956

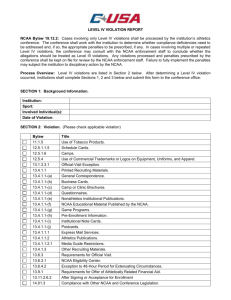

advertisement